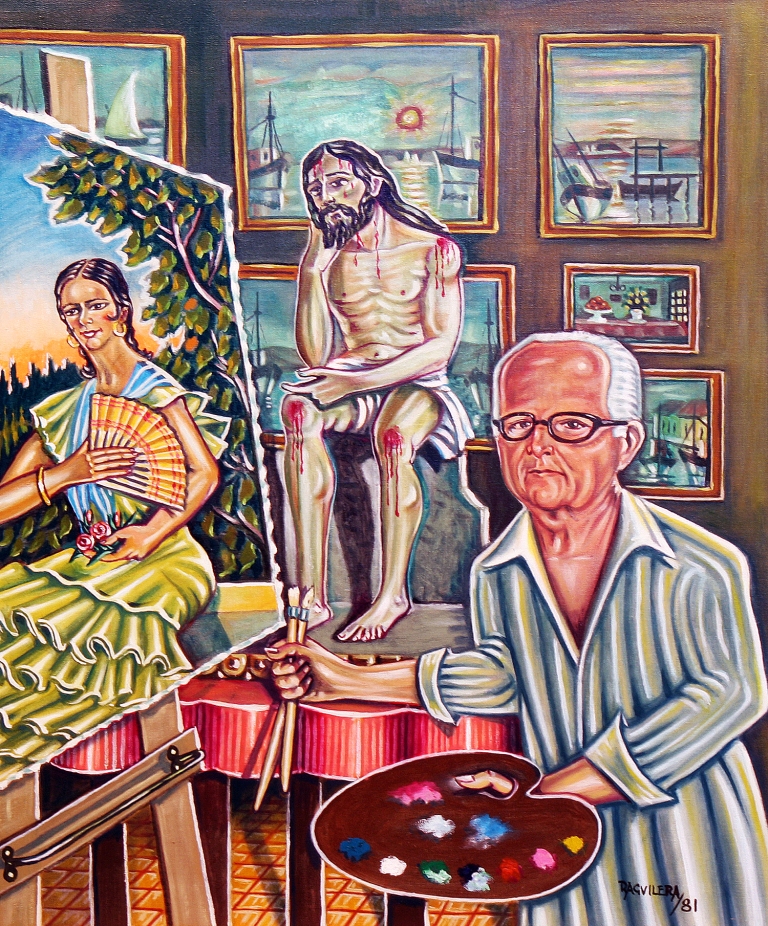

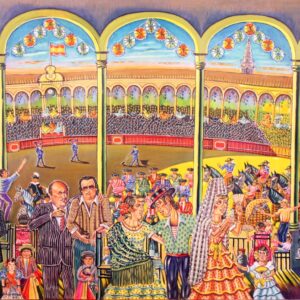

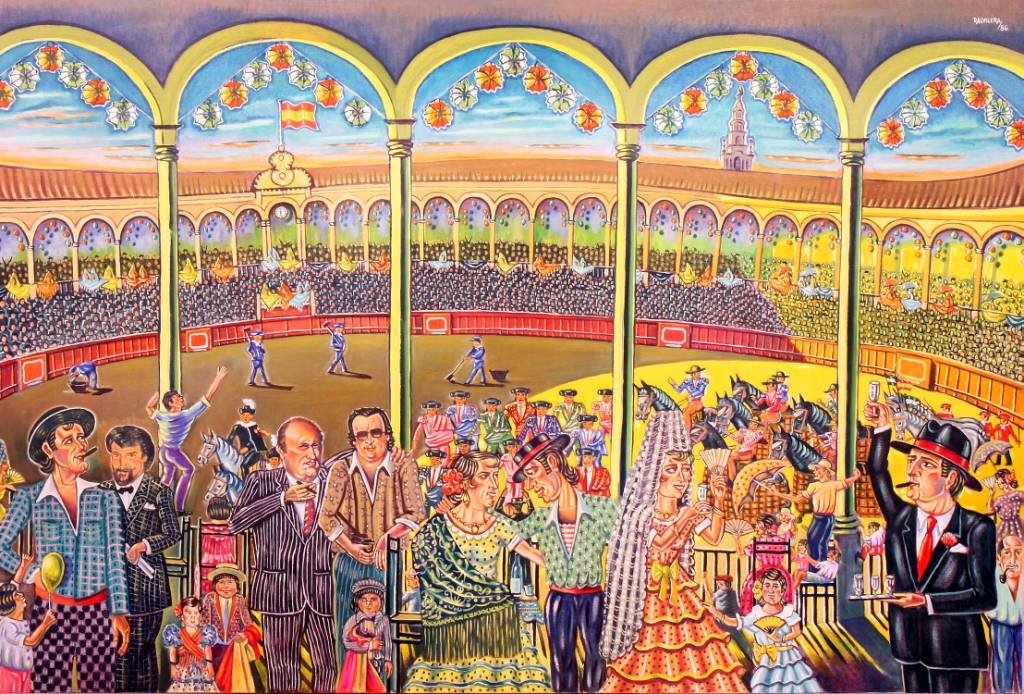

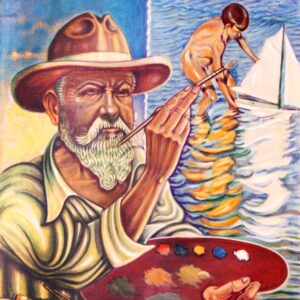

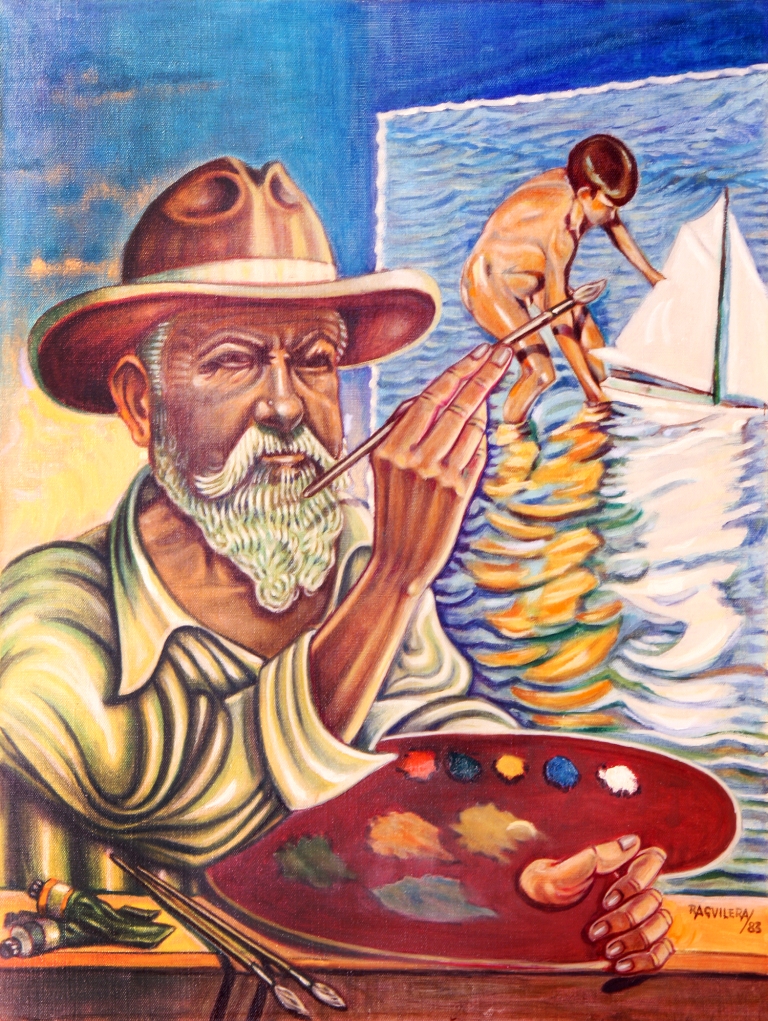

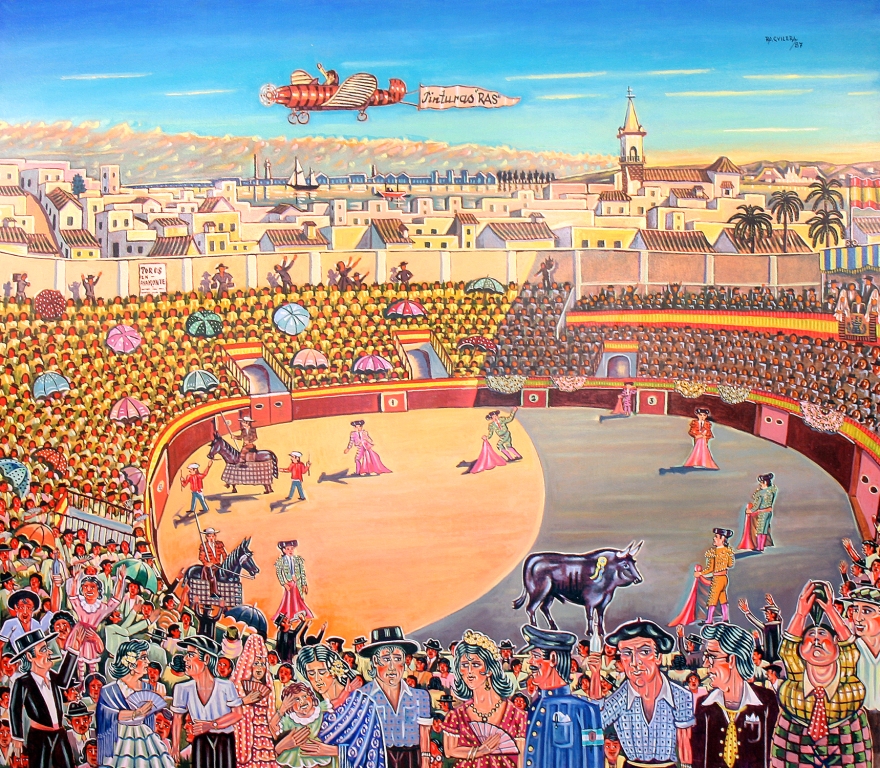

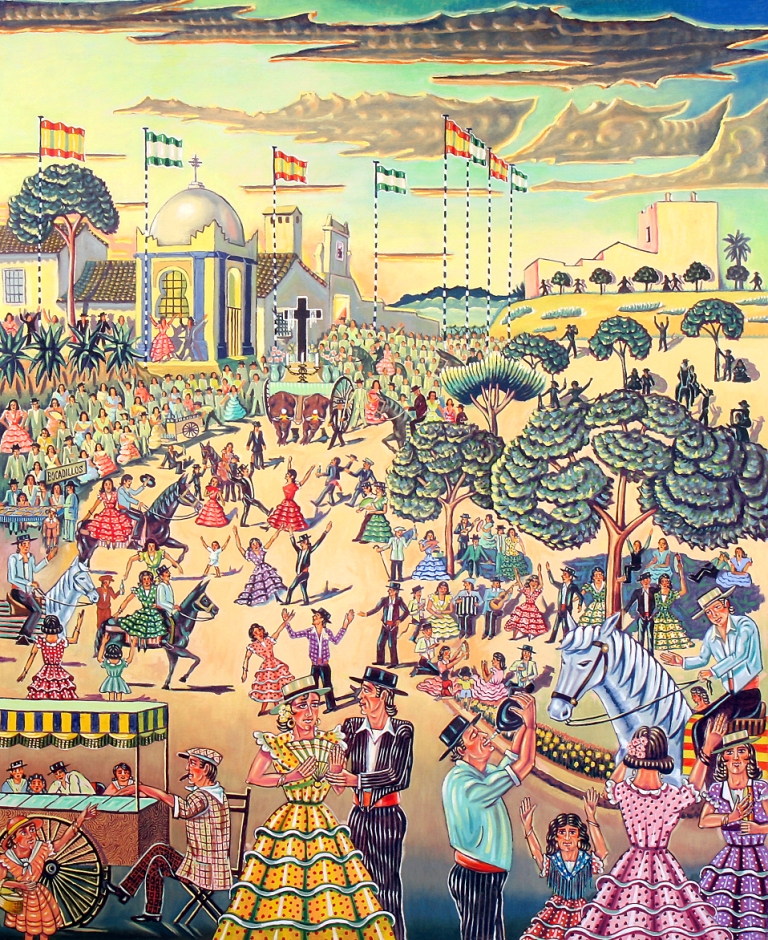

These works were created during a period of widespread hostility in the world, when contemporary art tended to respond to the constant barrage of angst with corresponding lightness. Yet, when Rafael does put himself in the picture, it is not with pride, as a royal or knighted figure, but rather as a cult figure—the matador—one of the most respected surviving folk heroes of Spain.

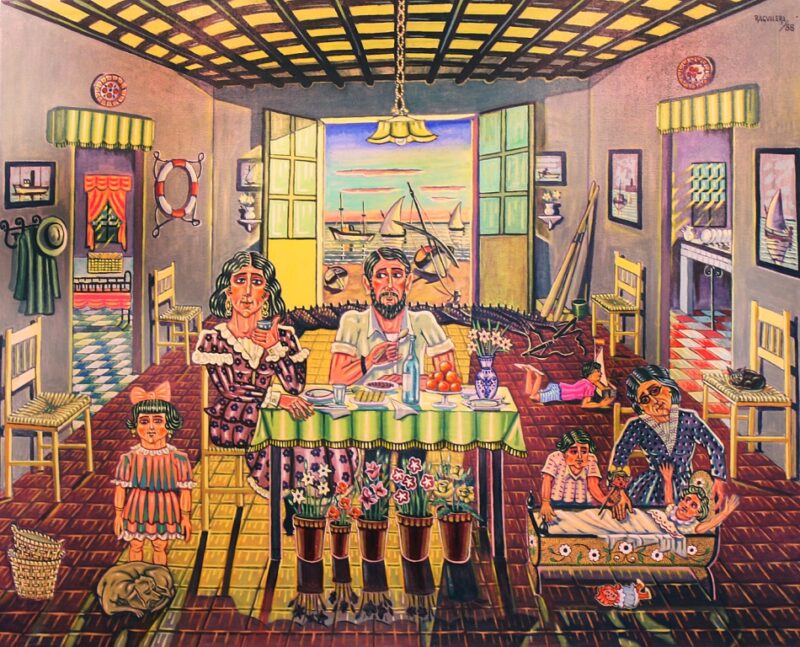

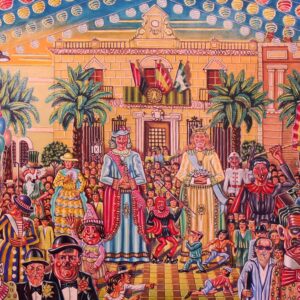

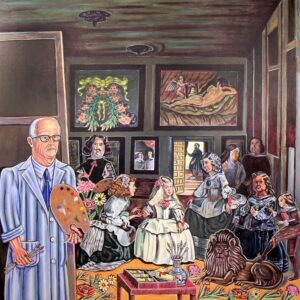

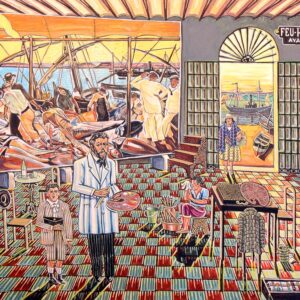

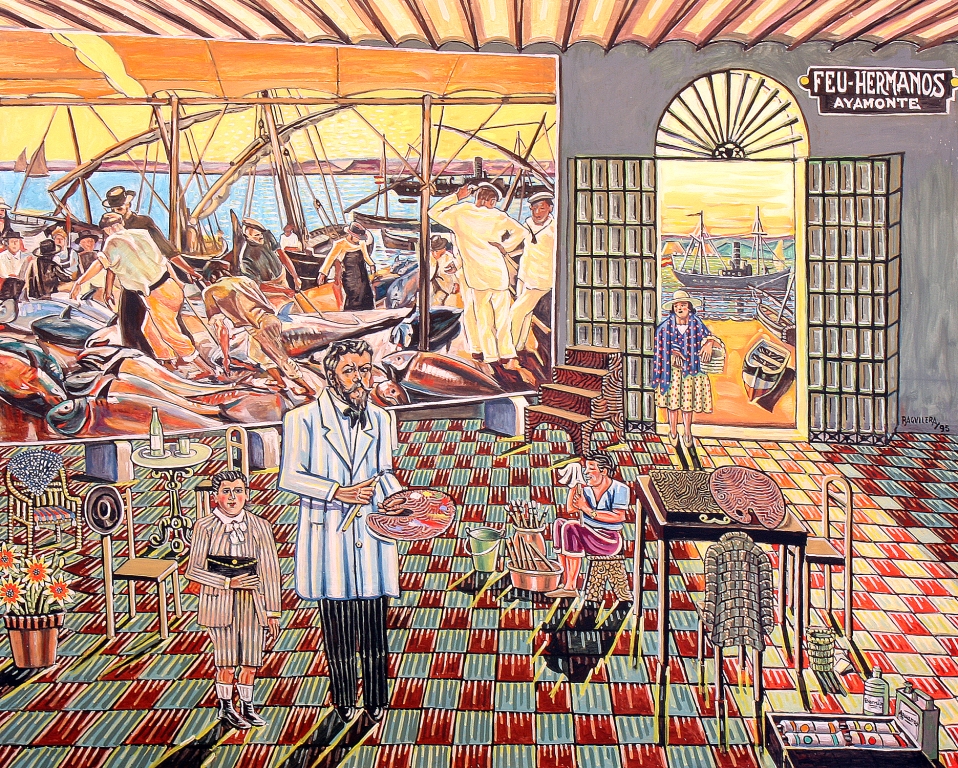

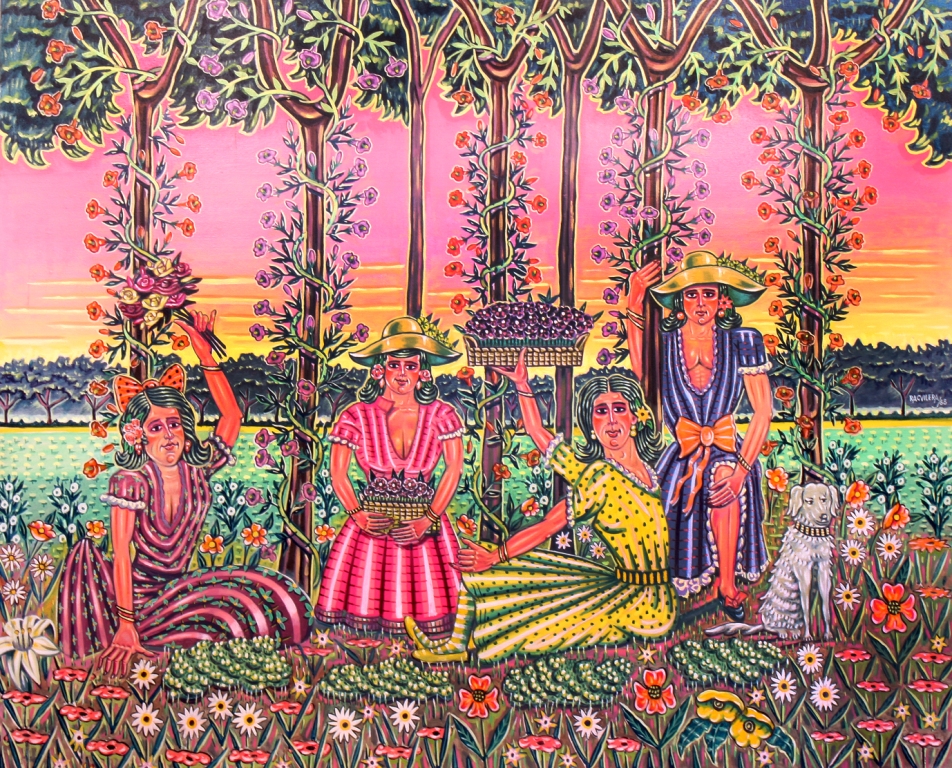

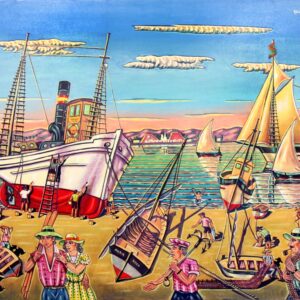

Instead of mere figure tableaus, Rafael’s are tableaus of human emotion. Each figure seems to have an inner life of its own, an individual spirit, as is clear in the portraits. Each personage seems focused on something other than the group portrait of which they are a part. The scenarios depict what usually occurs just before a group portrait is either photographed or drawn. Although the basic concept of the group portrait is more about the preservation of memory than anything else, Rafael sees the process of setting up the group composition as more important than the formality achieved once the group is composed. This is how he sees life itself, as the process of human actions, which interact to form a whole, not the static form of life—the consequences of what happens before and after actions occur; instances which tend to make us less arrogant and more human—moments when one is aware that one’s garments may look wrinkled, or one’s hair not properly arranged and combed. Nor is Rafael afraid at times to depart from his “crowd†scenes in order to delve with greater depth and seriousness.

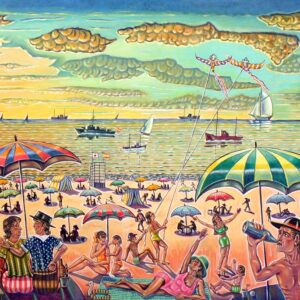

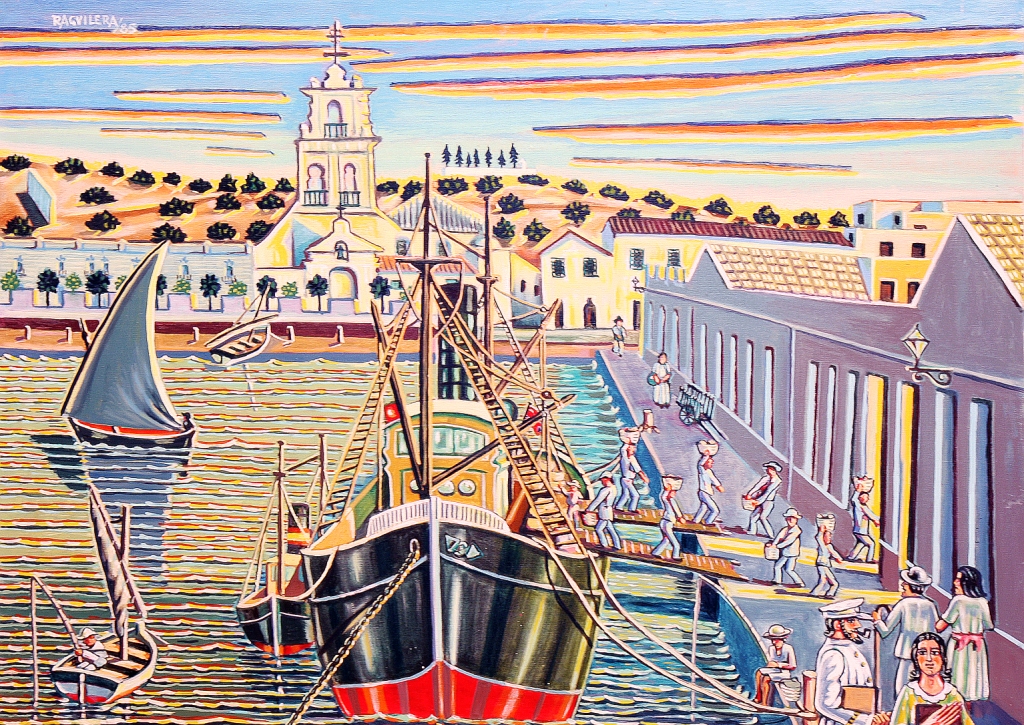

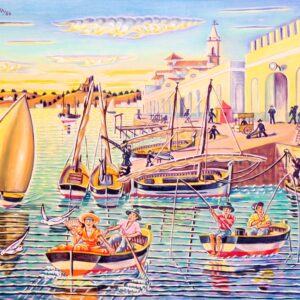

Rafael’s artistic process is a priceless mix of old-fashioned posing, which most of us have experienced at least once in our lives. His colors are straightforward. He seems to make no allowance for risk or error in the impulsion to continue and complete his voyage, so he seeks his subjects in the eternal world of nature, and in its daily process. What Rafael presents to us is the very heart and soul of his creative concept of life—which full of the particular notion that as long as there are people, life is worth living. He celebrates life every moment of the day, by expressing his artistic interpretation of how life is lived in Hispania. Rafael shares with us every nuance and quirk of human emotion. One need only look at his extant corpus to understand this. Every figure within the paintings has its own emotional wavelength, which is inscribed both on body and face, and he conveys all of this to us with every brushstroke he uses to create his realistic world. Whether one recognizes it or not, Rafael Aguilera is one of those gifted individuals who have been able to recreate the true essence of the life of a particular locale. In other words, he is one of our most valuable cultural figures—the genuine folk artist.