African Art has a secure place among the great art traditions. At first, the Western world recognized it through its influence on European avant-garde artists at the beginning of the 20th century. That influence initiated the advent of Modern Art, first by the breakthrough of Picasso but almost immediately by others. Exactly a century later, it is an anachronism to refer to African art as primitive. The cultural expressions from the continent of Africa are acclaimed in their own rights by scholars, collectors, museums, and the public alike their sophistication, vitality, and expressive effect have become widely recognized.

What the Western world first deemed as savage curios were, in their African context, objects imbued with power created through form, materials, color, and surface qualities. Now we have come to understand that African art is a vivid expression of African values and traditions and responds, as does all art, to influences and changing conditions. This art, from the religious, mythological, and historical to the decorative and functional are expressions from cities, towns, and villages where many of the traditions are alive, traditions that slowly evolve, reflecting changes in form and detail through shifting values, foreign influences, migrations, and new technology.

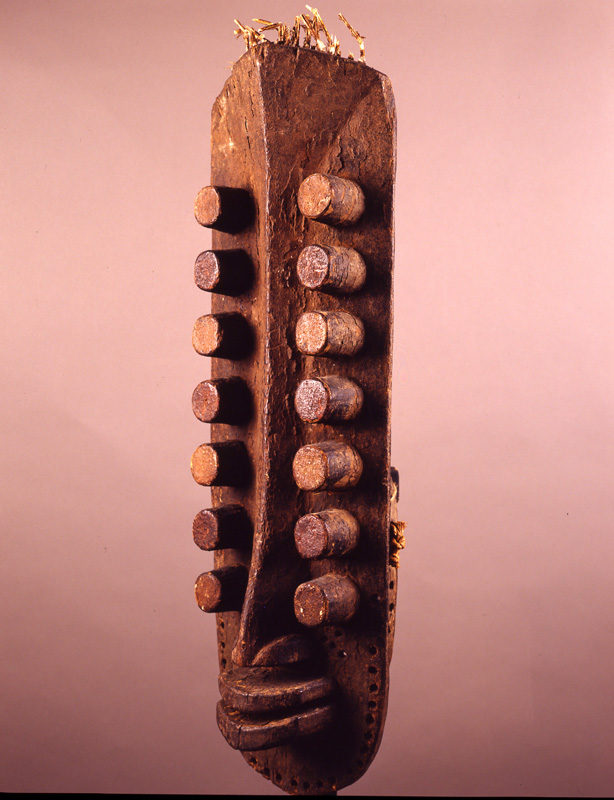

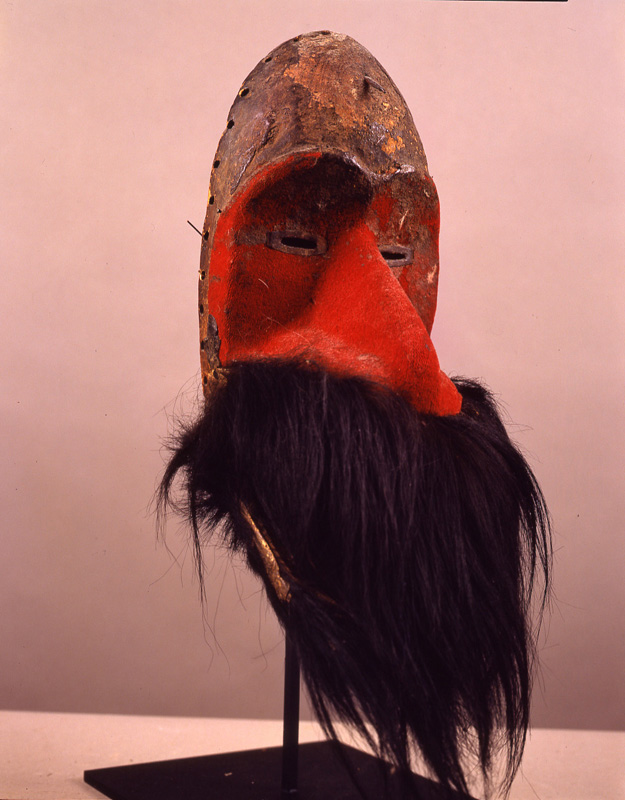

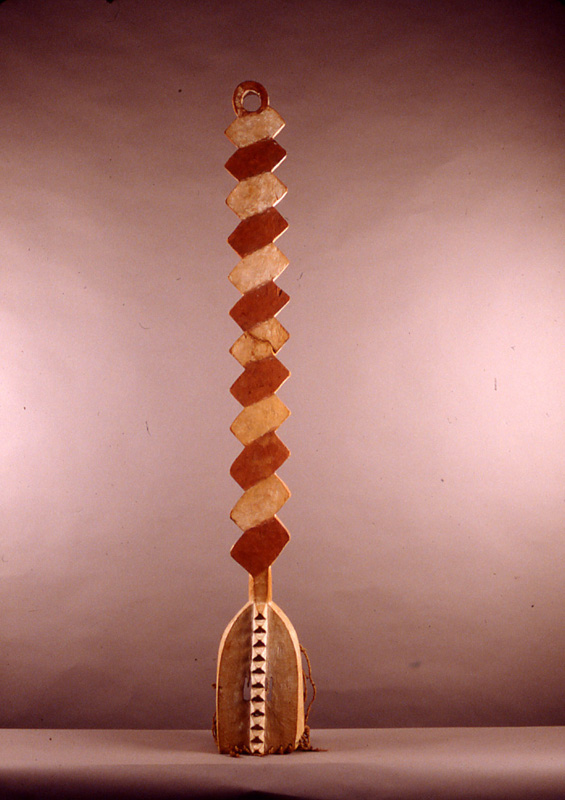

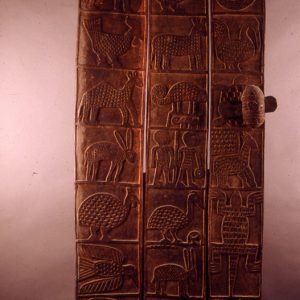

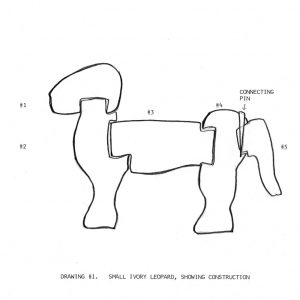

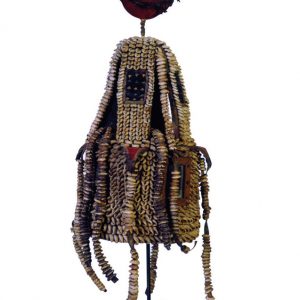

This exhibition of African art includes masks, figures, household and ritual objects, body adornment, ceremonial costumes, and textiles, from the Western Sudan, West Atlantic Coast, Central, East, and Southern Africa. Objects were selected for their geographical representation and aesthetic excellence. The exhibition displays the full range of ceremonial and practical objects produced on the African continent.

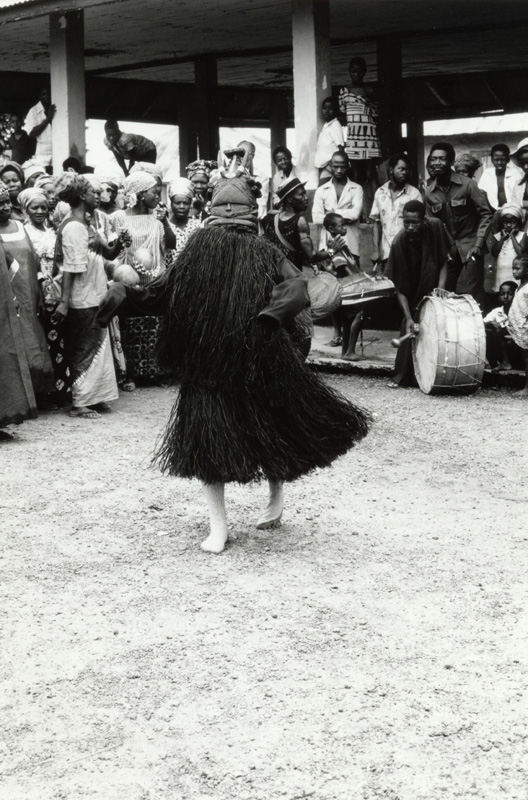

In seeing these sculptures, we are viewing only one aspect of the ritual or ceremony, divorced from the context that gave them cultural meaning but their power of imagination and qualities of form, surface, and craftsmanship still carry multi-dimensional values that affect us and to which we can relate. Moreover, we have included costumes in the collection, some for their consummate workmanship and beauty, others for their projection of power and magical properties. They too, are part of the larger expression of each African culture’s interaction between art and life (between the vital forces of gods, spirits, and ancestors).

African art is not ethnographic art but is Art. It is not craft (though it can display great craftsmanship) but it expresses a time a culture and an individual interpretation of that reality. If it is to be effective, it must adhere to communal traditions. It must encompass mythology, magic, religion, history, and local references. Yet it can express deep emotions and beauty through its volumes, shapes, lines, planes, proportions, details, surfaces, and internal relationships or architectonics. These qualities of art are understood and practiced by the master carvers but generally not discussed or written about in Africa. The art functions, not as wall decoration, but in shrines and masquerades for the life, survival, and continuing traditions of the community. It also functions as political art, for social criticism and prestige, often carrying status symbols of leadership and royalty.

The basis of African aesthetics can be fundamentally explained by one word. That word in many African languages means both beautiful and good. The beautiful/good is pleasing to the senses, virtuous, correct, useful, appropriate, and conforming to custom and expectations. It is a summation of the values of African art.

Pieces are arranged in the traditional geographical order, from the Western Sudan, West Atlantic Coast, Central Africa to East Africa and finally South Africa. Most of the major sculpture-producing areas are represented.