Through an extraordinary set of circumstances, Miklós Müller found himself at the center of the Hungarian art world for more than half a century.

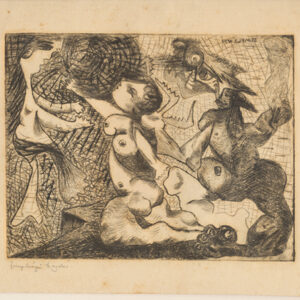

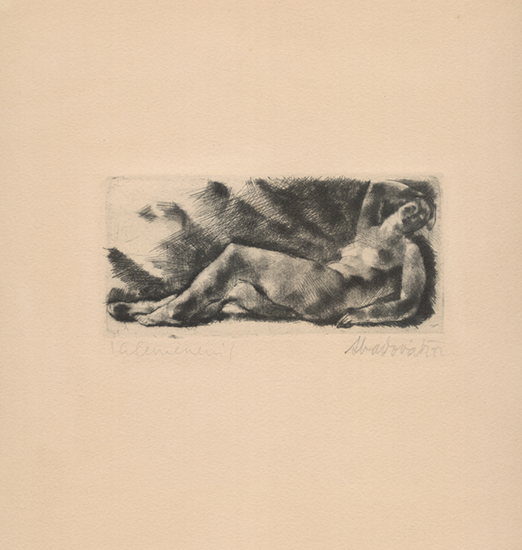

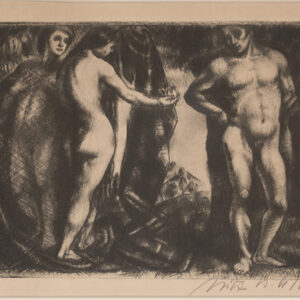

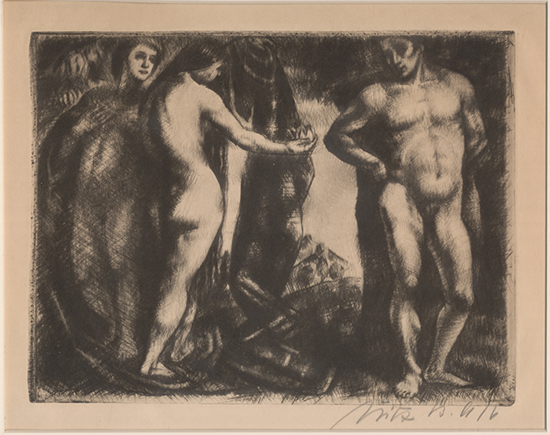

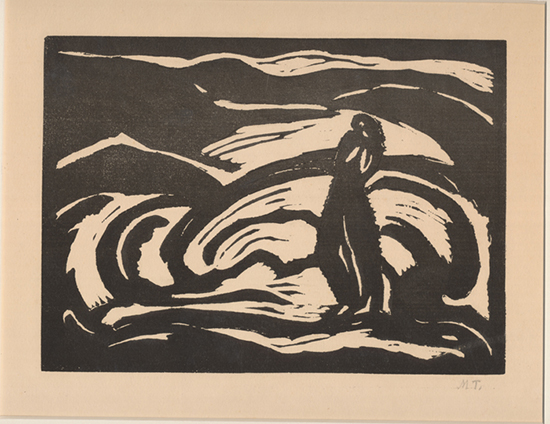

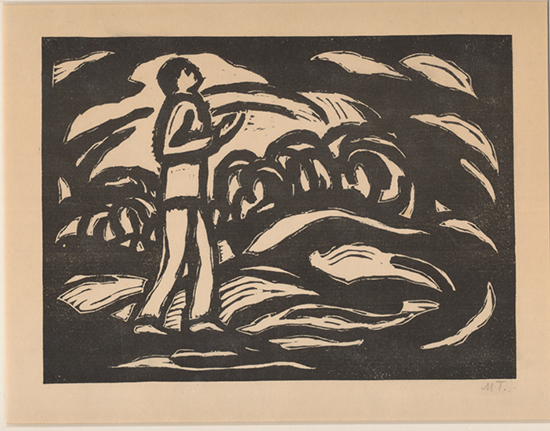

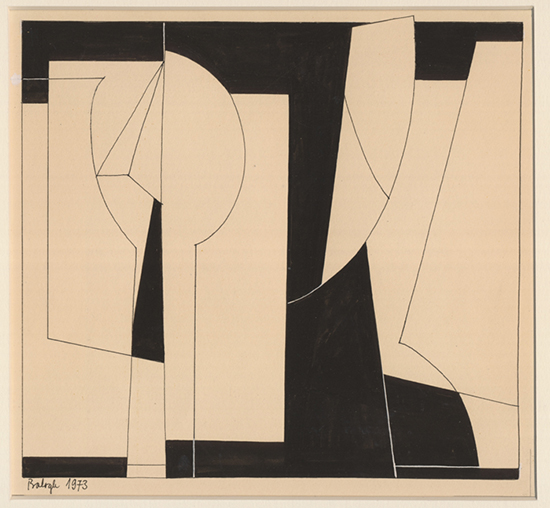

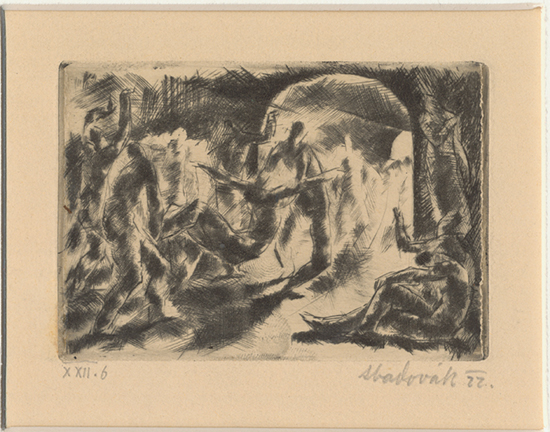

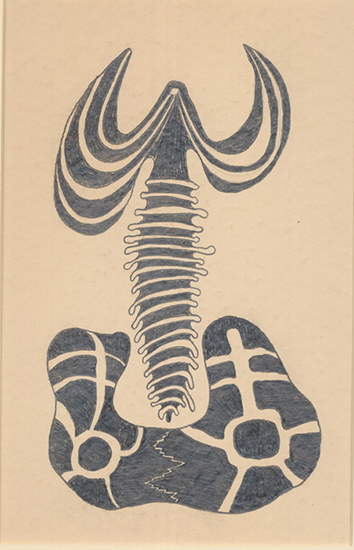

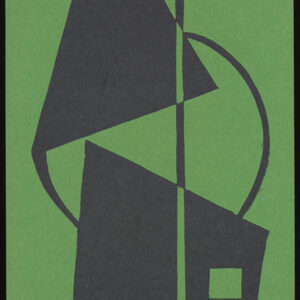

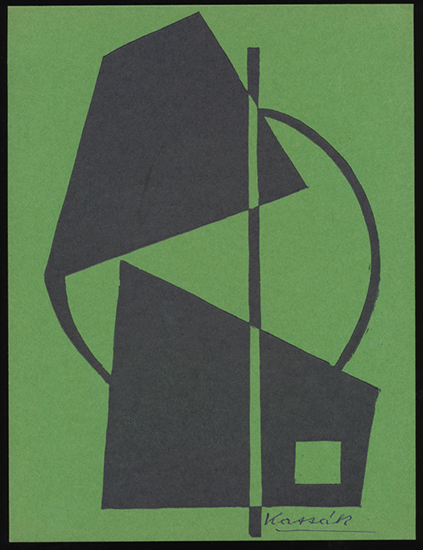

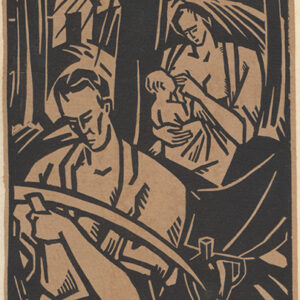

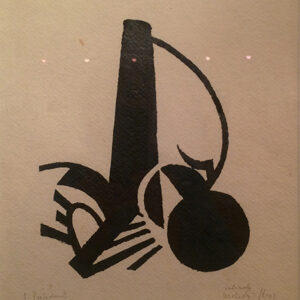

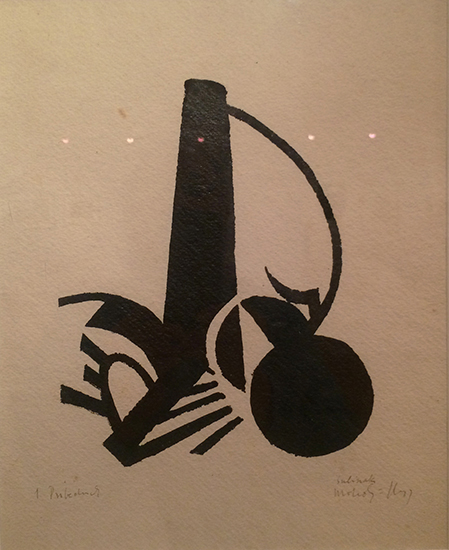

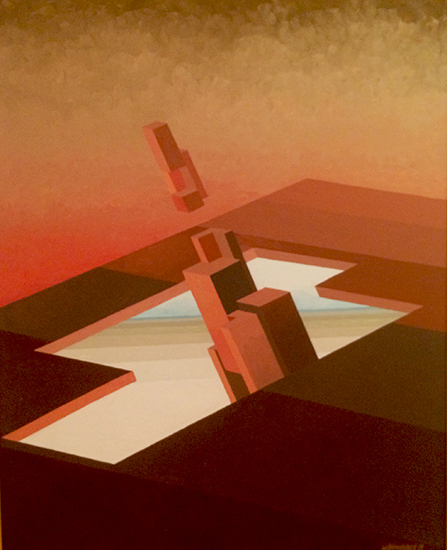

First, as a young biologist, in 1957 Miklós Müller met—and later married—Noemi Mezei. Her father, Arpad Mezei, was an art historian and critic, author and philosopher, and a respected touchstone for the artists and writers of post-World War II Hungary. Ãrpad Mezei founded the European School, “a concentration of philosophers, writers, and artists formed in 1945 and incorporating abstract and concrete elements from a starting point of radical expressionism moving through surrealism.†As the name suggests, this group was rooted in, and aimed to continue the heritage of European avant-garde movements. When Soviet Communist elements forced Hungary to adopt a Communist constitution in late 1949, these Modern artists were soon expected to adopt Stalin’s preferred art style of Socialist Realism, which glorifies workers and Communist heroes through realistic depictions. Those who refused to conform felt the heavy hand of the state suppressing them: they were silenced, ignored, and forced from positions of authority.

Noemi and Miklós Müller collected the art of this oppressed artistic circle and received gifts of artwork from Noemi’s father, Ãrpad Mezei. In 1964 they were able to immigrate to the United States due to Miklos Müller’s outstanding scientific work. He was invited to take up a position at Rockefeller University, where he remains Professor Emeritus today.

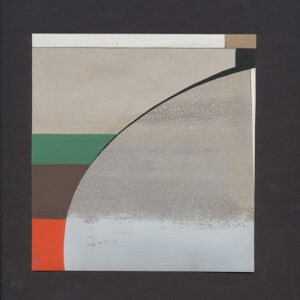

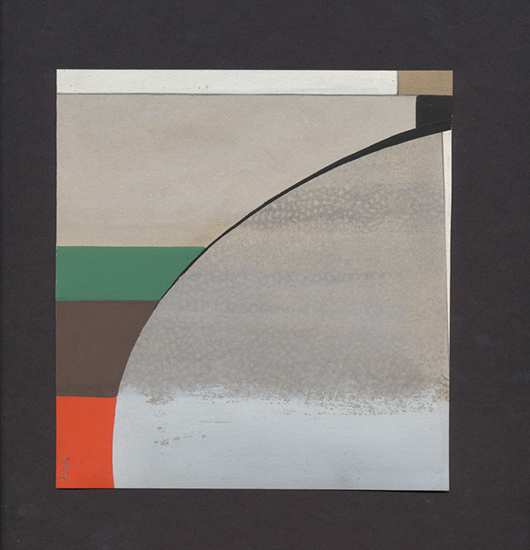

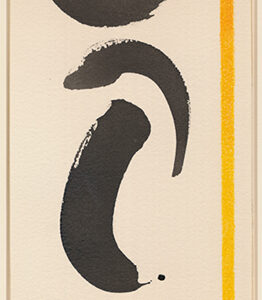

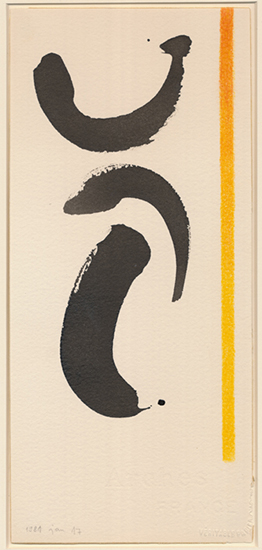

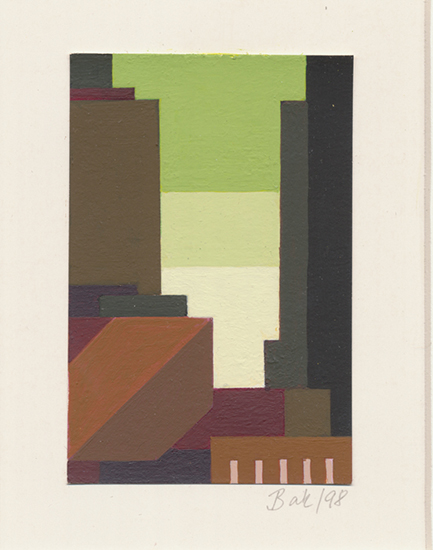

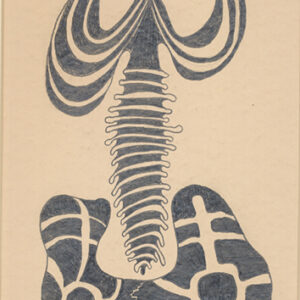

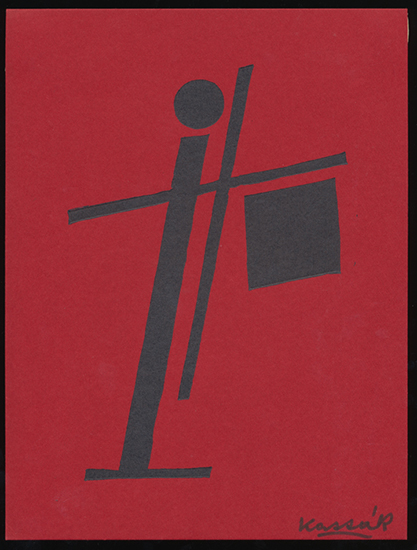

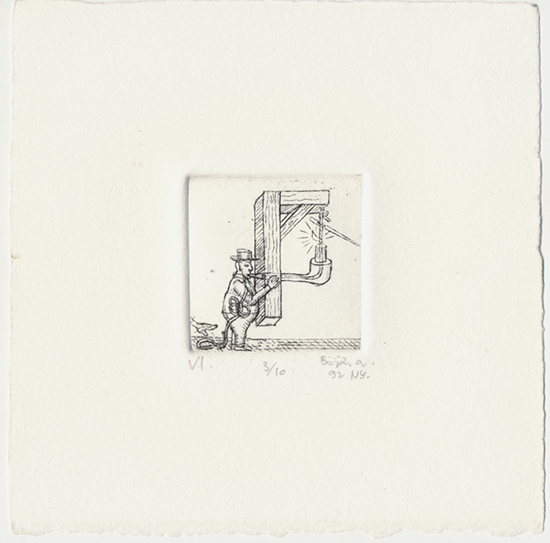

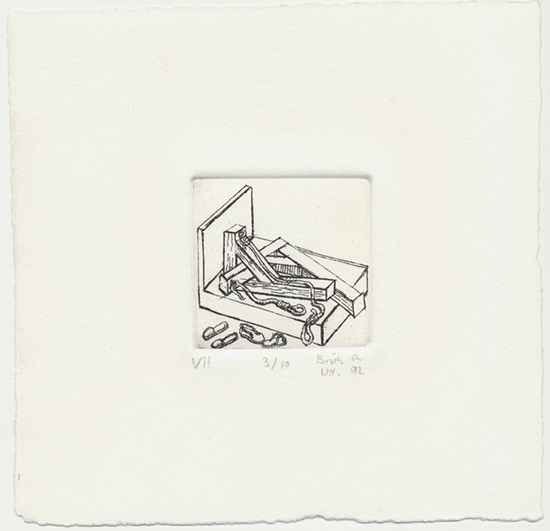

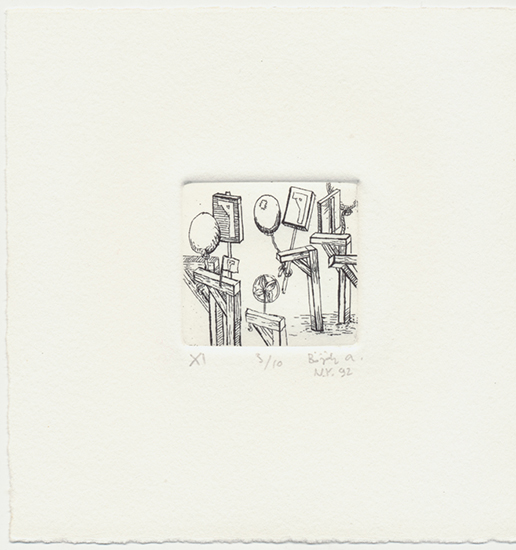

In 1965, the artist Jószef Jakovits settled in New York, and became a close friend, as testified by many Jakovits works in the collection, represented by several on display here. During the 1970s, Milos Müller and his second wife, Jan Keithly, both American citizens, began to travel to Hungary. Miklós Müller renewed old relationships, and the couple formed new ones, including a new generation of Hungarian artists working in styles disapproved of by the State. As travel restrictions eased, the Müller apartment in New York became a center for artists visiting from Hungary. Many stayed there; some even used it as a studio. The Müller-Keithly collection continued to grow as the collectors met younger Hungarian artists living in New York.

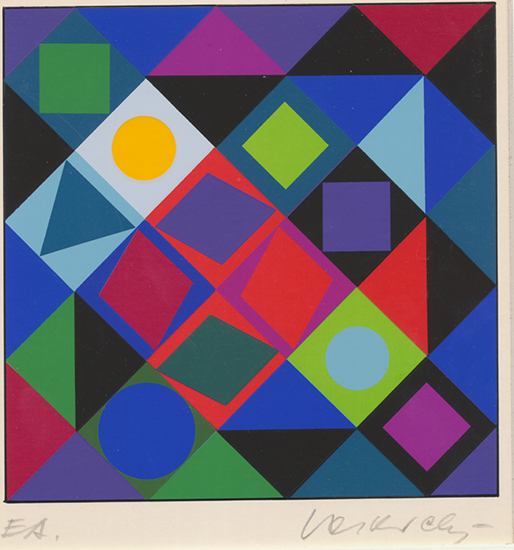

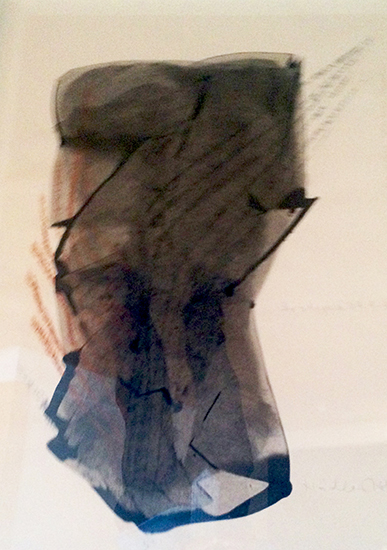

The selected works on exhibition here give an idea of the scope of the collection, spanning much of the twentieth century, especially concentrating on the 1950s onward. Behind almost every work on display is a personal relationship between the artist and the collector.

After the fall of Communism in 1990, the Hungarian artists once repressed, overlooked, and ignored enjoyed a revival. During the last twenty-five years, they have been belatedly recognized as a vital slice of Hungarian heritage and saluted for bravely sustaining the artistic pursuits of the free world, although, unfortunately, many did not live long enough to savor this.