That a single photograph from a Nazi album and a sixteenth century engraving by Albrecht Dürer should give birth to the rich array of visual representations assembled in this catalogue is a tribute to the power of images to stimulate the imagination of the artist. The anxiety and confusion masking the face of the boy with his hands raised as he is marched to an uncertain destination cry out for response, but the obvious option of pity seems utterly inadequate. Similarly, the gloom suffusing the face of the angelic figure in Dürer’s engraving titled Melancolia I (1514) forces the viewer to engage in a silent dialogue with this apparently disenfranchised messenger from heaven to uncover the sources of its distress. Both photo and engraving present us with a complex legacy and an ambivalent sense of the future, multiplying the possibilities of interpretation through variations on their original themes. As the artist reworks the images over and over in a seemingly endless creative outpouring, we are invited to confront the contradictions they raise about the physical and spiritual destiny of mankind. We are left searching for meaning and purpose in the human journey even as we meet repeated obstacles to achieving that goal.

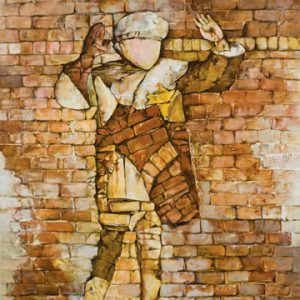

Samuel Bak is a visual poet of the modern imagination, using familiar images in his dramatic canvases to cast a relentless light on the dilemmas that continue to haunt our civilization. Though we may instinctively feel sympathy for the Jewish boy with his hands raised, paradoxically the intention of the picture, which was taken by a German photographer, was to rouse exactly the opposite response—contempt for a people who represented a threat to the plans for a racially pure Thousand Year Reich. The photo was one of a series depicting the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, gathered in a volume and intended as a birthday present for the leader of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. It was thus meant to celebrate rather than to lament the extermination of a people, and Bak’s inventive versions of the vulnerable boy introduce numerous alternatives to this bizarre objective. Indeed, how to preserve the memory of the dead, those victimized not only by mass murder but also by the other forms of war and violence that have defined recent centuries, remains a major challenge to those who have lived through them or inherited their legacy of loss. Since the penalty of forgetting is oblivion, Bak’s variations restore to our consciousness one courier from among those who have vanished, and this grants to the boy a kind of immortality that countermands the German desire to erase his existence. He is an emissary from the grave whom the power of art restores to a symbolic life, bearing the burdens of his anguish, but in so many guises that we must struggle to gain access to the significance of his far from heroic doom.

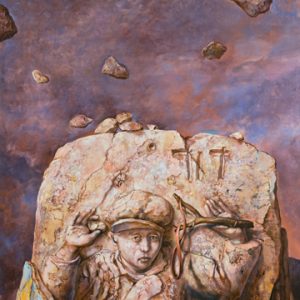

Our failure to attend to his fate would sentence him to return to the anonymity of the landscape that originally consumed him. This is one import of Walled In (BK1242-L), where the outline of the boy is absorbed by the wall of brick that comprises the only scenario of the painting as he gradually fades from view, much as his fellow Jews lost their identity when their physical bodies were reduced to ash. To be “walled in†is to allow the self to disappear, whether through choice or external compulsion, and anyone attuned to how our social and economic environments seek to pillage our privacy will understand that such threats need not be limited to the history of the Holocaust.

The paintings in this series achieve a dynamic dimension by addressing each other—this is not the first time Bak has used this device—as if they constituted a pantheon of figures each granting its own pedestal but circling the viewer so that all are visible at the same time. The various versions of the boy are in dialogue with each other in a kind of silent communal debate about identity; and since we do not know who he is, his image remains fluid, detached from personal history. Led by the artist, we are drawn by this strategy into experiencing how memory and imagination can rescue death from the void of history and turn absence into a palpable presence. Thus in Crossed Out II (BK1242-C), the boy is distinct from his background, certainly not yet a pure “portrait†but at least an individual awaiting a destiny. In the original photograph, the boy is by himself but also surrounded by a crowd of other Jews, though the worried expression on his face suggests a dawning recognition that neither community nor family will be able to help him now. In Crossed Out II (BK1242-C) he emerges physically from the bricks of Walled In (BK1242-L), though the monotone of the entire painting still links his garments to the color scheme of his brownish surroundings. The punning title teases us into further speculation since the boy bears on his body, not one “cross†but two: the “X†that appears in both wood and rope evokes the mystery of his anonymity and his fate while the slanted crucifix that encases his body (with doubtless a deliberate irony) reminds us of the earlier execution (and resurrection) of a less anonymous Jew. Bak associates the lot of the boy with the idea of Christian crucifixion, but only to detach it, since nowhere in the original photograph or in Bak’s various versions of it is there even a hint of redemption. The Christian narrative offers a meaning for sacrifice which has been passed on from generation to generation without change, whereas the proper word for what happens to the boy is murder, not sacrifice, though as we know some commentators seek to ease the pain of what lies before him by imposing a hopeful idiom on the prospect of meaningless death.

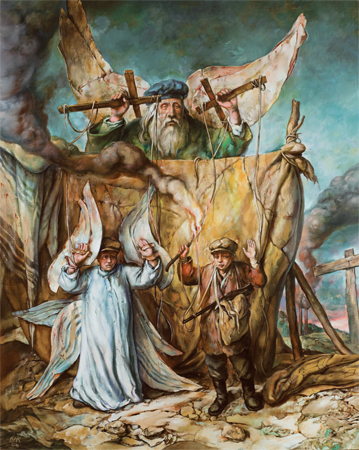

The idea of human sacrifice in connection with God’s purposes for his chosen people enters Hebrew scripture through the story of Abraham and Isaac, and Bak includes several references, again ironic, to this early narrative, partly as a contrast to the later Christian version. Christian theology chronicles the sacrifice of God’s “only begotten son†for the sake of redeeming mankind and making salvation possible. In Genesis the Lord tests Abraham’s faith by ordering him to sacrifice his “only sonâ€â€”presumably his only legitimate one, since Abraham has also had a son by the handmaiden Hagar—but as we know God saves the boy at the last minute and rewards Abraham with the following promise: “because you have done this thing and have not held back your son, your only one, I will greatly bless you and will greatly multiply your seed, as the stars in the heavens and as the sand on the shore of the sea, and your seed shall take hold of its enemies’ gate.†(Gen. 22: 16-18.) Bak combines some of these themes in a painting like Holding a Promise (BK1242-H), which unites the fate of the Warsaw ghetto boy with the crucifixion of Jesus (through the stigmata in the boy’s palms) and the sacrifice of Isaac (through the bundle of firewood that is hung from his neck), adding an allusion to Noah’s flood (through the voyage by water and the fragments of rainbow at the top of the sail) when God reaffirmed his covenant with his chosen people. If we return now to the original photograph, we witness the failure of those promises to reach fruition, and the unseaworthiness of the craft in Holding a Promise (BK1242-H) carries little reassurance for success. The meaning of a “chosen people†has been redefined with a savage irony by the members of the so-called “master race.â€

How is the imagination of the viewer grapple with this complex interaction among memory, faith, history, and a doomed future? Instead of multiplying the seed of Abraham like the “sands of the shore by the sea†(which are barely present in Holding a Promise, BK1242-H), the Germans nearly achieved the exact reverse: in Bak’s painting, the boy’s future is literally behind him, not before him, a voyage upon a watery surface that contains no hint of a destination and no sign of divine presence or protection. The works are not accusatory, however, but simply reminders of the spiritual dilemma that intrudes on our consciousness as we recall a biblical narrative that the events of history seem so easily and so thoroughly to have thwarted.

The artist may not be accusatory, but his creations are free to invade our composure with a starkly unsettling display. In Collective II (BK1204) a horde of amorphous figures vaguely resembling the outline of the boy, numbering in the hundreds if not thousands, approach a crude altar whose contents bring us back to Crossed Out II (BK1242-C), only this time a stone barrier separates them from the spot where Abraham in a test of faith agreed to sacrifice his son, while the scattered nails and wooden cross are once more a clear allusion to the Crucifixion. But now we are forced to concede that these are inappropriate precedents for what awaits these boys—more than one million Jewish children were murdered by the Germans—and to confront an atrocity that carries no spiritual implications but requires an entirely new visual vocabulary for its criminal dimensions to be appreciated. In the distance, the clouds of smoke rising from the earth invite us to separate history from scripture, since we know the destiny awaiting the crowd of nervous but unsuspecting children. The title Collective II (BK1204) may be seen as a disarming euphemism for “mass murder,†and the painting may be viewed as a preliminary assault on those religious traditions that once regarded “sacrifice†as an entry to divine heritage. The altar and its trappings provide a retrospective ironic glimpse at two familiar sacred narratives that are less outmoded than simply irrelevant to the host of children who is perhaps clamoring for a connection that the imagination cannot establish. Their future is more allied with the clouds of smoke that rise from the earth in the distance, an “ending†that neither Abraham nor Jesus could have anticipated during the holy rituals with which they have long been identified.

Bak has a unique ability to make silent images speak, to force them to interact with each other (and with us) with a visual eloquence that echoes volumes despite the absence of speech. In Burning (BK1242-B) Bak examines a new term in the lexicon of our spiritual legacy, “martyrdom,†as the narrative of sacrifice culminates in the horrifying image of the boy set afire while still alive. On the ground lie the knife and the rope from the original story of the binding of Isaac, now discarded to be replaced by an association with Christian martyrs who were burned at the stake in an earlier era. But they at least had their faith to console them in the final moments of their dying, whereas for the boy there is no evidence of ties to the divine, no voice of God emerging from the dark cloud above him. If this is to be the fate of the boy from the photograph, to die alone without solace, it is no wonder that for all its dramatic eloquence the painting continues to leave us, its audience, distraught and speechless.

The ingenuity of allying the Nazi photo with Dürer’s engraving Melancolia I is brilliantly confirmed by the juxtaposition of the two in Elegy (BK1242-E), whereas in Walled In (BK1242-L) the figure of the boy, which is disintegrating before our eyes, merges with its inanimate background while ironically the angel retains its vibrant identity. What is the subject of its brooding? Is it trying with its broken wooden rule to measure any remaining ties to the divine amidst the fragments of shattered faith that surround it? We see God’s rainbow promise from the story of Noah’s flood, now reduced to an arc of wooden wreckage, as well as the stigmata of the Crucifixion on the palms and the star of David on the boy’s tattered garment, but these guarantees of ties to the divine seem not to inspire the angel, who sits fretting about the difficulty (if not the impossibility) of integrating these disparate images into an integrated portrait of spiritual reality. Is it aware of the sinister cluster in the distance, the icon of the Holocaust, the twin chimneys belching smoke into the sky, their neutral tones in stark contrast to the bright hues in the foreground? The broken rule in the angel’s hand is, like Crossed Out II (BK1242-C), a punning reference to a larger dilemma, since the fate of the boy, and specifically of the Jews, means that the spiritual rules by which civilization has professed to live, and for which the angel is a visible emissary, have been broken: if the various pledges of divine guardianship have led to this unspeakable atrocity, then only a legacy of bitter irony remains.

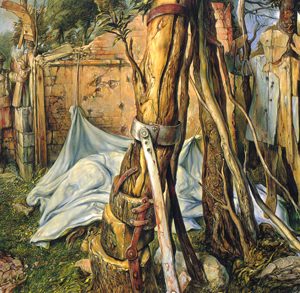

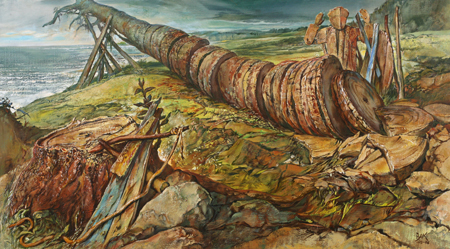

This irony extends to the act of creation itself since Bak is engaged in the composition of decomposition, of ordering chaos, no easy task when most audiences expect some form of organized beauty to emerge from a canvas. In Winds of Ponari (BK1124) Bak plunges his saddened angel into the abyss of the Holocaust, though the viewer is forced to interact with history as well as art to follow the trajectory of its contents. Ponari is the site outside Vilna where the city’s Jews, including the artist’s father and grandparents, were slaughtered by the Germans and buried in mass graves, their corpses later exhumed and burned so that no traces of the crime would be left. What role can a helmeted angel, immersed in the memory of such violence, play in this visual drama other than to sit morosely and wonder what spiritual conduit can possibly lead from such death to eternity? The painting is one huge question mark, as it were, raising explosive issues (to which the detonator in the lower left-hand corner is a silent trigger) that the imagination is forced to pursue by a host of provocative images. The angel’s lidded eyes seem to be gazing at the pair of shoes, which in Elegy (BK1242-E) had already turned to a monumental stone but here retain the vitality of their absent wearer. How do we mourn his disappearance, or the loss of thousands of Vilna’s Jews whose charred bodies lie beneath the terrain upon which the angel sits while the winds of Ponari blow over the scene without evoking a token of their prior existence? The painting forces the viewer’s imagination to do some excavating of its own, but this has always been the major challenge of the Holocaust, as well as of other atrocities that have recurred repeatedly in the modern era. Why do they exist, and where do they fit into our more familiar narratives of human progress and spiritual goals? The landscape of Elegy (BK1242-E) is covered with road signs, but their surfaces are blank and they offer us directions only to nowhere.

The landscape of Dürer’s Melancolia I is filled with signs and images too, but his angel contemplates the vastness rather than the futility of the task that lay before the inquiring mind. Created at the cusp of the Renaissance, the engraving presents the meeting of an age of faith and age of scientific discovery not as a violent clash or a dismal rupture, but as a vast as-yet unanswered question about how mankind will resolve any conflicts such an encounter might bring to our understanding of the physical and spiritual cosmos we inhabit. The ladder, intact here but broken in so many of Bak’s works, suggests the possibility of rising to new spiritual heights, while the polyhedron and sphere, the scales and hourglass, and even the calipers in the angel’s hand introduce ways of measuring physical and temporal reality that would end in the revolutionary space-time theories of an Einstein. In 1514, a world lay before Dürer that roused both anxiety and hope. Today, a world lies behind Bak, and behind us, demanding a redefinition of both. Neither the progress of science nor the expectations of faith can ignore the mayhem of atrocity that each must bear as part of its legacy for the future. Bak’s view is retrospective, and in Appearing (BK1131) he begins to sum up the role of the angelic messenger today who in the beginning called out to Abraham and said “Do not reach out your hand against the lad, and do nothing to him†(Gen. 2: 11-12). Where was that intervening voice when the Germans rounded up the boy from the Warsaw ghetto?

In Appearing (BK1131) fragments of Dürer’s original vision remain, but the additions make all the difference. The ladder now has nothing to lean against, pointing aimlessly toward the sky and held in place by a taut rope connected to a support outside the frame of the picture. The polyhedron is there, but the sphere is missing, replaced by a cube in the shape of one member of a pair of dice. The unused calipers lean against it, as if to announce the new role of random chance in a universe once ruled by exact physical measurement or controlled spiritual design. Instead of an arched rainbow and a dazzling light in the distance, we find some ominous chimneys in the background, spewing their sinister smoke toward the heavens. The hourglass has been replaced by a clock face, blank except for the Roman numeral VI. It still tells partial time, but it is attached to a brick and stone structure resembling one of the tablets that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai, prompting us to recall that the sixth commandment in Hebrew scripture is “Lo tirtsach,†“Do not murder.†It takes little effort to remember that the same numeral evokes the six million Jewish dead of the Holocaust.

But Bak is not content to leave us plunged in the gloom of a ruined civilization, our eyes dimmed by the detritus of its remains. An unexpected image intrudes on the scene in the shape of a solitary pear, and with his fondness for punning Bak includes its name in the title of the painting. Those familiar with his work know that earlier he devoted a whole series to the single image of the pear: why has it escaped from its original context to appear in the terrain of Dürer’s angel, who is brooding on the fate of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto? Next to the single die, with its unsettling reference to random chance, we find a dissected pear, as if someone wished to seek out the mystery of its ripe beauty amidst all this decay. Its startling visual presence cannot redeem the gloom of its surroundings, but it constitutes a revelation nevertheless of how art can contribute to our understanding of history—and Bak achieves this repeatedly in his visions of organized chaos—by stressing the paradoxical nature of reality, which inspires the creative impulse even amidst the incidence of human pain. It would be convenient if we could conclude that Appearing (BK1131) represented the end of our journey, but that is not how this series works. The shift in consciousness required by each painting as we encounter fresh emphases leaves the viewer burdened with the task of a never-ending quest for tranquility and reconciliation, a worthy goal so distant that it may very well be unreachable. In Figuring Out (BK1242-F) the very title defines our principal responsibility in facing the ongoing conflict between the fate of the body and the future of the spirit. Here the figure of the angel is considerably diminished; it has abandoned the tools of science and turned to a book whose text may contain some insight into the grim spectacle before (and behind) it. Behind it stands a cancelled community, its blocked entrances and empty windows raising the question of where all its residents have gone. But unlike our encounter with Winds of Ponari (BK1124), we need not linger here over the answer: the angel is gazing at a mass grave containing layer upon layer, in the form of giant wooden cutouts, of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto, transformed into inanimate material and dominating the landscape before us. To the left of the cutouts two hands emerge from the earth in mute entreaty, but we are given no clue as to the nature or the object of their appeal. During the past few years a Catholic priest has been traveling through Ukraine, having made it his life mission to uncover every last mass grave in the regions where the Germans buried the remains of murdered Jews. Populations there must now “figure out†how this could have happened in the twentieth century, just as Bak’s angel puzzles over the atrocity that the earth has disclosed. Like the angel, they know what they see, but they do not yet “see†what they “know.†It is a classic example of the challenge of the visual imagination when art is the intermediary between perception and understanding.

I alluded earlier to a time when most of Western Europe believed in the “controlled spiritual design†of the universe. Few people of faith doubted the link between a benevolent Creator and His creation. The Holocaust has turned that into a problematical issue, and Bak sums up the dilemma in In Their Own Image (BK1242-J), a clear but ironic reference to the statement from Genesis (1:22) that “God created the human in his own image.†Here the Warsaw ghetto boy has split into two selves, as if his physical and spiritual destinies were now isolated from each other. Although the painting seems to offer some kind of triangulated intimacy between the ancient winged figure above and the boys below, they are separated by an intervening curtain, part Jewish prayer shawl, and part fragments of a Star of David. The contemplative angel of Dürer has now adopted the role of puppeteer, through careful inspection reveals that no rope is connected to one arm of the human boy while the flaming torch he carries is about to sever the other. The empty crucifix to the right, with the twin smoking chimneys nearby, sums up one of the most charged implications of these paintings: that a narrative of salvation or divine intervention in no way consoles or compensates for the narrative of the murder of the Jewish people. Perhaps a new narrative is needed to answer the question of how the boy can fulfill his human destiny and his angelic nature at the same time. If history has moved beyond Genesis, if these two alter egos are now products of their own images, divorced from the divine, if life is no longer a spiritual “performance†derived from some heavenly origin—In Their Own Image (BK1242-J), with an almost apocalyptic intensity, knows what to ask, but together with its fellow paintings it leaves to the eyes and mind of its audience the difficult duty of building a future for the human spirit that will tolerate the paradoxical and ironic vision it conveys.