It seems unlikely that Andy Warhol – who made the Disaster series and the Electric Chairs and who was the artist with whom Ultra Violet has been most closely associated – would have contemplated doing what Ultra Violet has done here. Warhol’s Disasters are deadpan, cucumber cool, distanced by their tabloidesque gothic origins, and, for those of us who have kept outside of the prison population, his Electric Chairs have met fictions, known only through photographs or through, well, those Andy Warhol’s. 9/ll though was an actual, raw, and culture-altering event, an event not yet sunk into history and prickly with premonitions of things to come. Not Warhol territory at all.

Ultra Violet has sailed right in though. Is she being insensitive? Opportunistic? Or does she simply accept that this happened, that it can and should be dealt with? Theodor Adorno, an oracle of the Frankfurt School, along with Herbert Marcuse and Walter Benjamin, famously wrote No poetry after Auschwitz. This was immensely moving, utterly understandable and, of course, predictably wrong But has there been good literature or art about Auschwitz? That is another question entirely.

There has been powerful art in the past about atrocity – Goya’s Disasters of War, Guernica – but the sheer math of what we have proven capable of since World War I, whether the events were intentional, like Hiroshima and the Gulag, or the product of ineptitude, dishonesty, and cowardice, like Chornobyl and Fukushima, has tended to daunt visual artists, often reducing them to kitsch, like the lamentable Unknown Political Prisoner project in post-war Britain and much AIDS-inspired art. There are wondrous exceptions, like Christian Boltanski’s oblique evocations of the Holocaust but they are not undyingly expressionist. They work slowly, like novels,

Memorials, of course, are not just art about destruction, suffering, and death. They have a specific function. The cover of the August issue of Harper’s is headlined The American State of Terror and carries an image of the World Trade Center before the strike, and an essay by David Riefff, “The Limits of Remembrance,†examines that function.

Reith notes that Hitler once gloated that the general forgetfulness of the Turkish mass slaughter of Armenians would mean that the Nazis’ genocides would also be forgotten. Reith also notes that memorials are not occasions for nuance, for self-critiques, but to bring about what the French historian, Ernest Renan, called “large-scale solidarity.†For that reason, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Damien Hirst were soundly smacked for remarks that aestheticized the event and for that reason the avant-garde composer Steve Reich, whose new album WTC 9/ll includes fifteen minutes inspired by the attack, came under such pressure that he dropped his plan to use an image of the burning towers and a hi-jacked plane on the cover. But Rieff also notes, bleakly, that all memories fade. He quotes Roosevelt describing Pearl Harbor as “a date which will live in infamy.†Well, did you remember that it was December 7, 1941? I didn’t.

But times do change. History in a world of Facebook, Yahoo, and Google is perpetually refreshed, and ever bright, and September 11, 2001, kicked off a cycle of history. “La Terreur was coined during the French Revolution,†says Ultra Violet, who was born Isabelle Dufresne. It might be noted that Warhol had suggested Dufresne call herself Polly Ester but she found her nom de superstar in a copy of Scientific American.

“There were events before 9/11 but this was such an extraordinarily well-orchestrated blow,†she says. “9/ll is for me the official date of the beginning of the Terrorist Era in the United States.†It will surely retain this deep, dark significance until, just as Pearl Harbor leaked meaning when the West faced other enemies during the Cold War, that cycle has evolved into something different.

When. If.

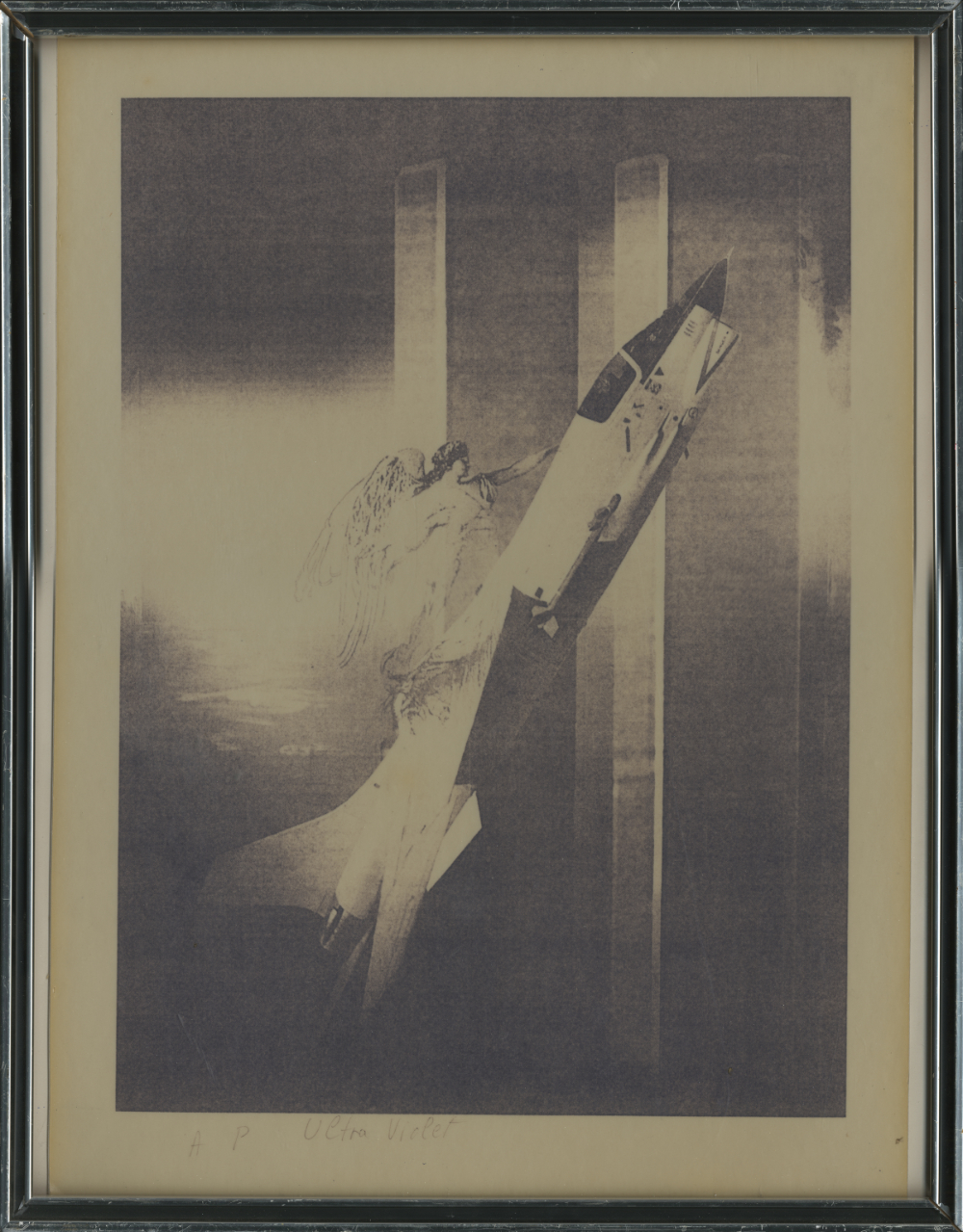

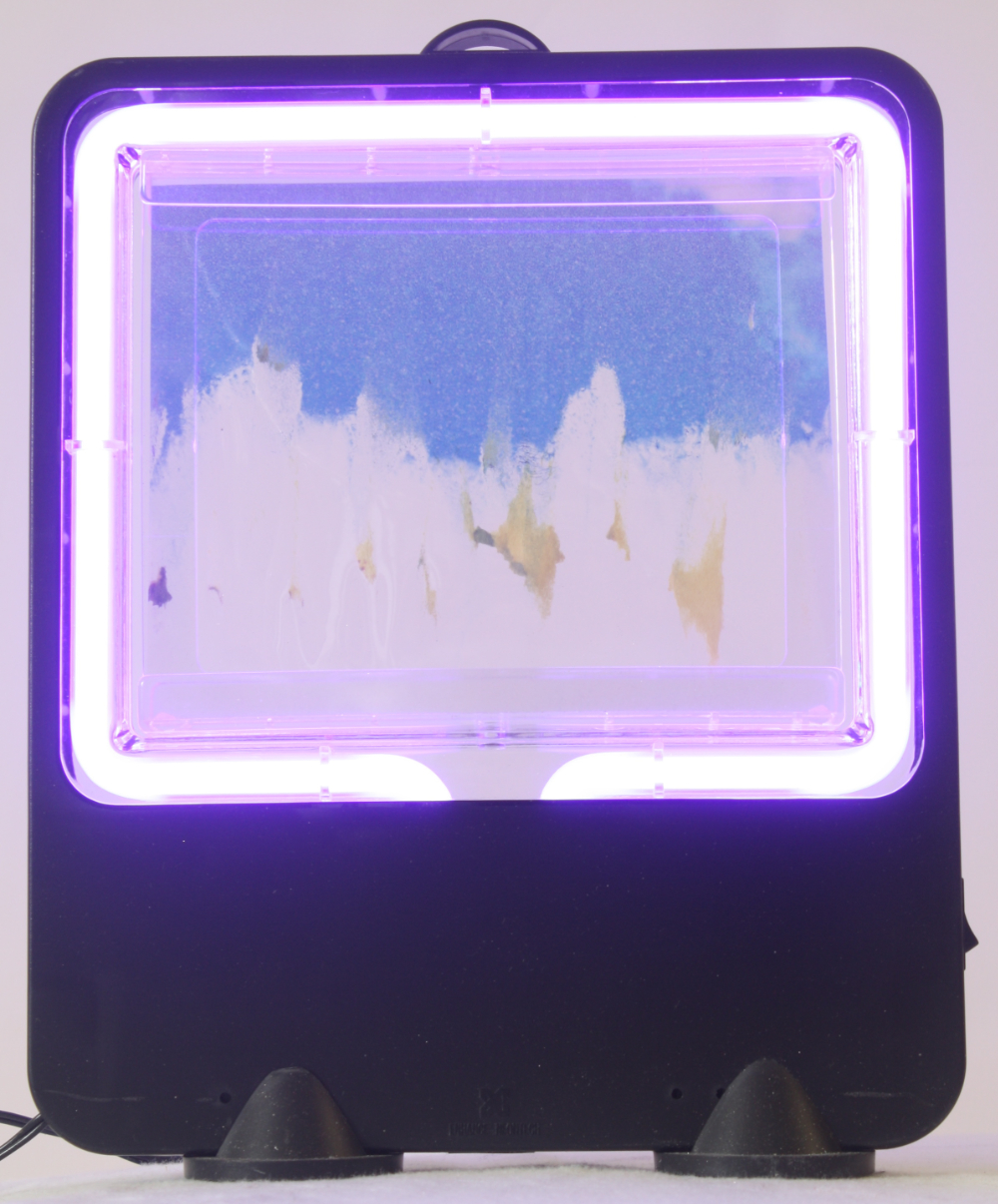

Ultra Violet was in Manhattan on 9/11 but in her uptown apartment. She heard about it right away. “I knew immediately that it was a terrorist attack and not an accident,†she says. She volunteered and worked down on Ground Zero for a spell with the Salvation Army. “I’m not much of a one to volunteer but there I did,†she says. Amongst her first attempts to find a pictorial vocabulary to express her feelings were paintings and drawings of Mickey Mouse falling off the tower.

“But people don’t want to see that,†she says, “Some people got very upset. But nobody should be upset about this. Because my feeling was that Mickey Mouse died that day. I think the naiveté, the hahaha, then let’s keep smiling, of this country, you know, it took a blow. And I’ve done some portraits of Mickey Mouse with his date of birth, 1928. And the date of death. 9/11/2001.â€

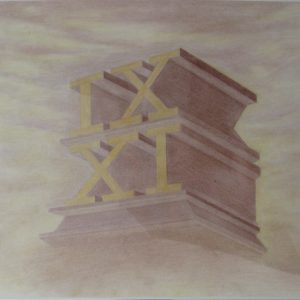

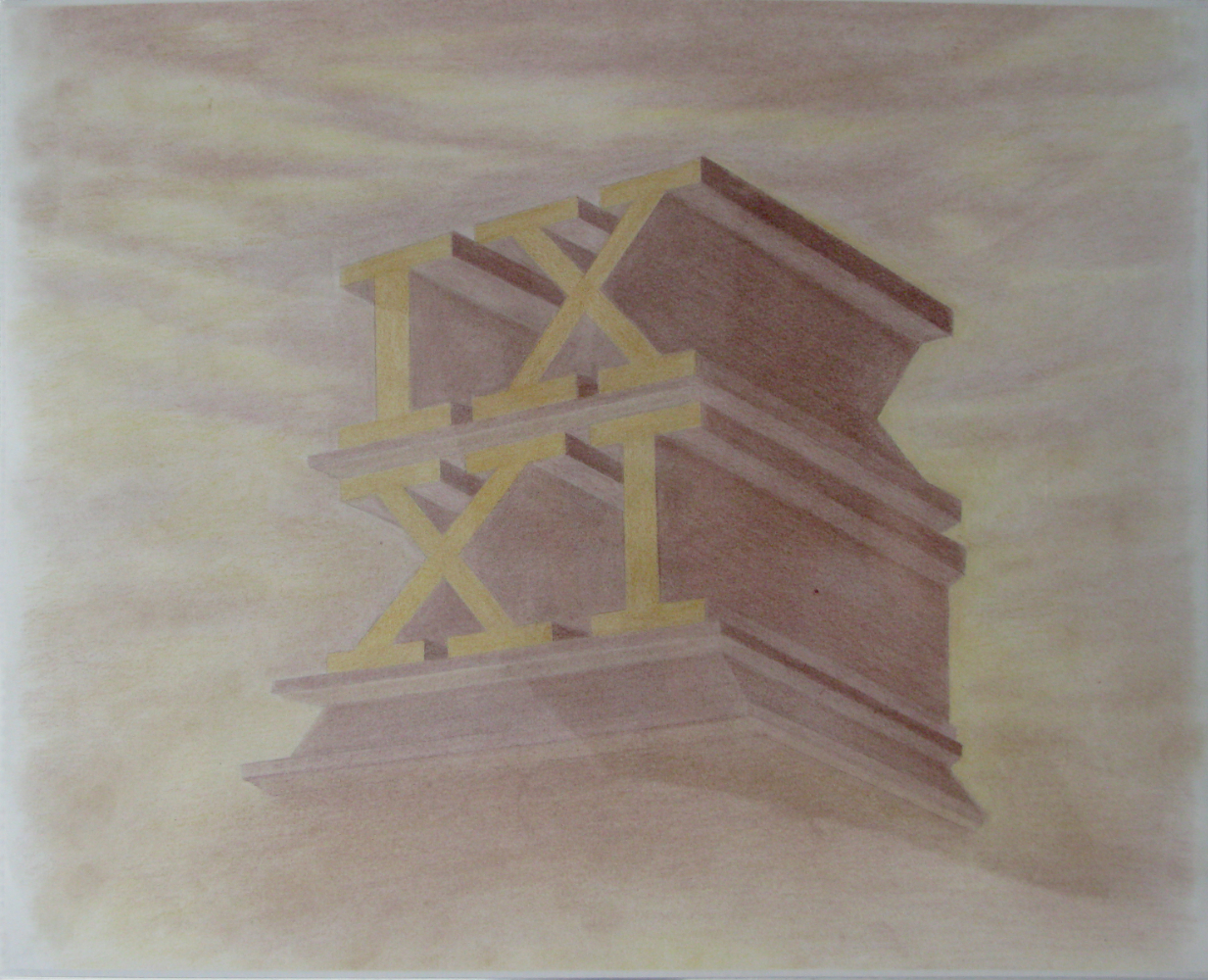

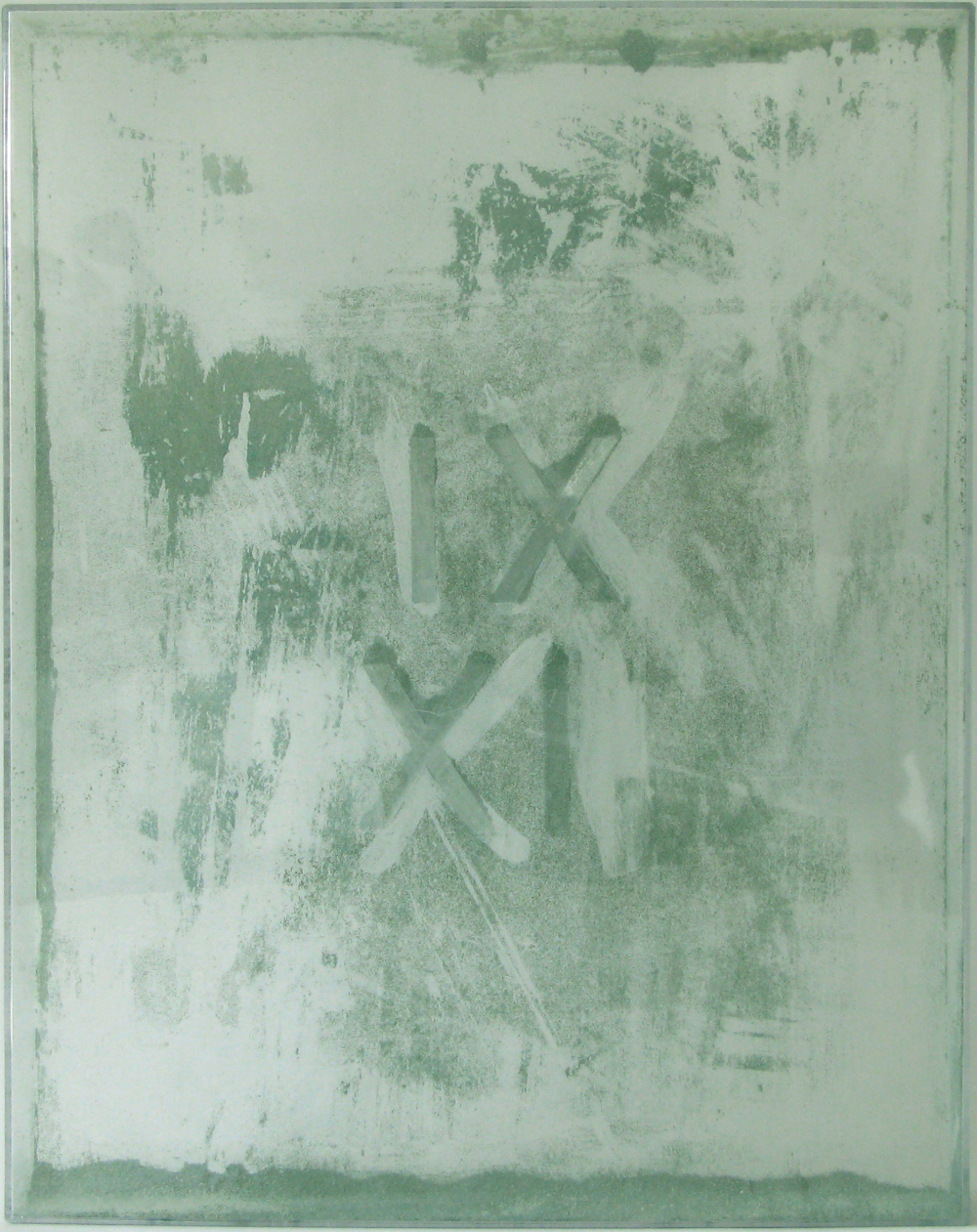

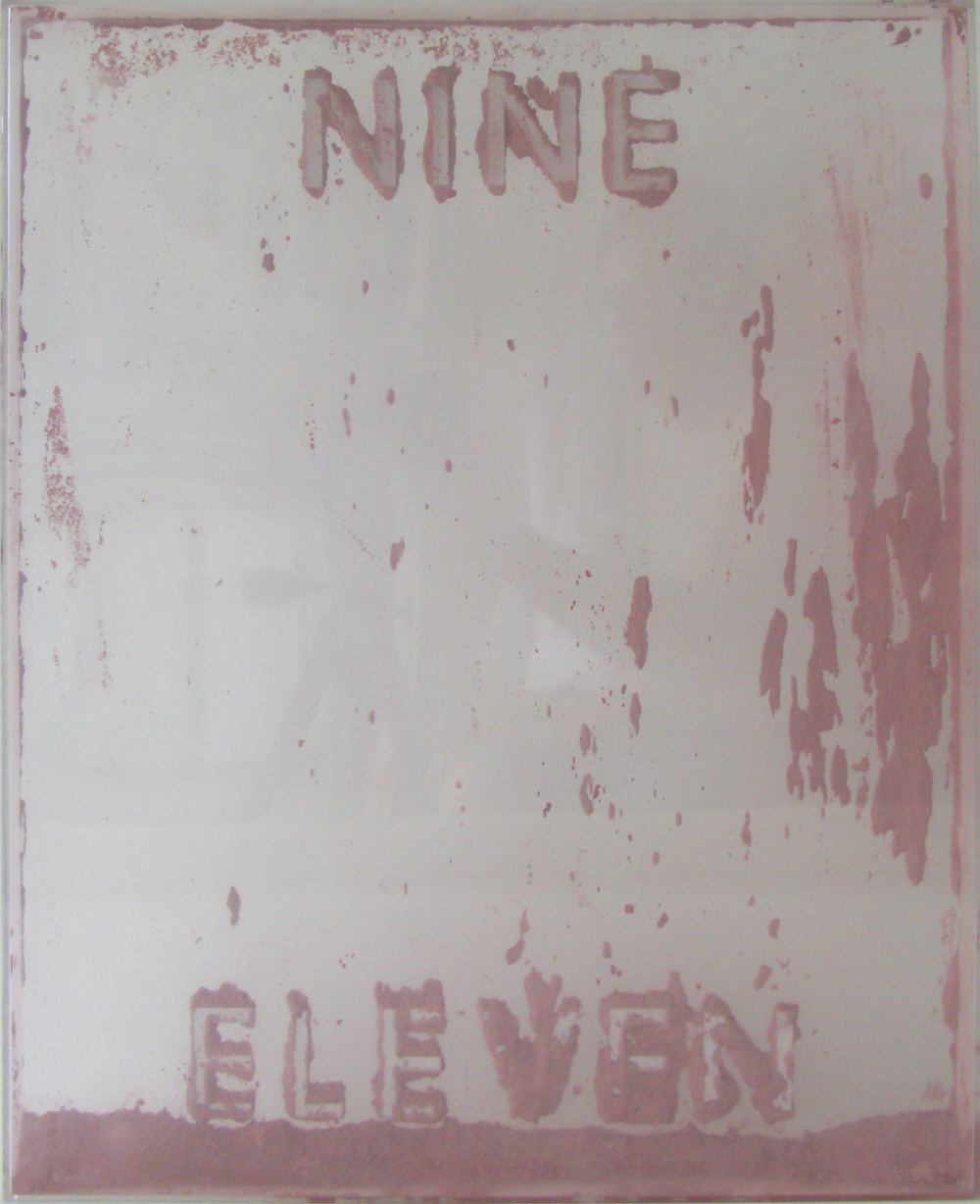

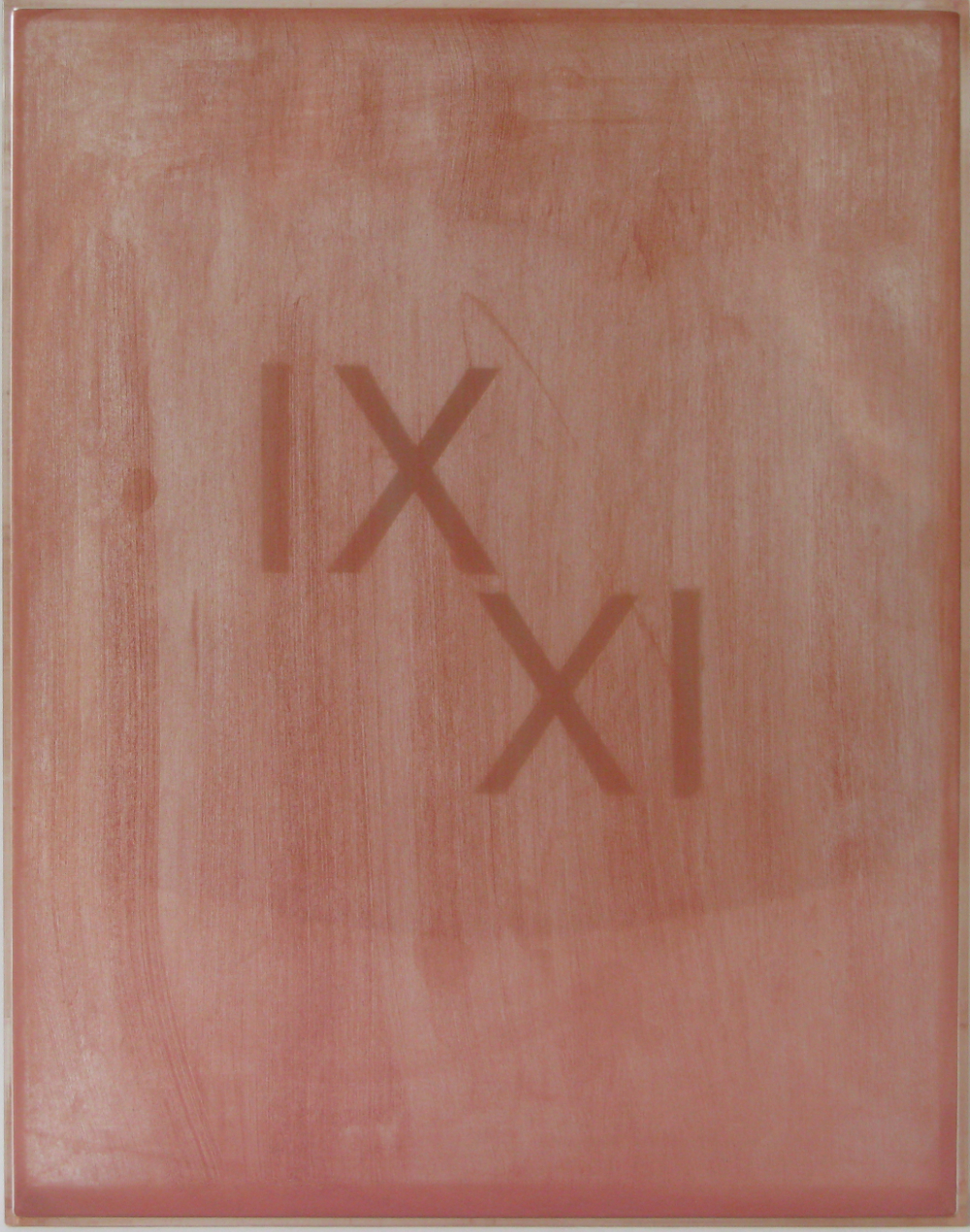

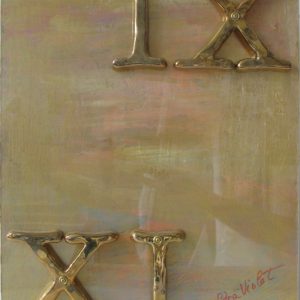

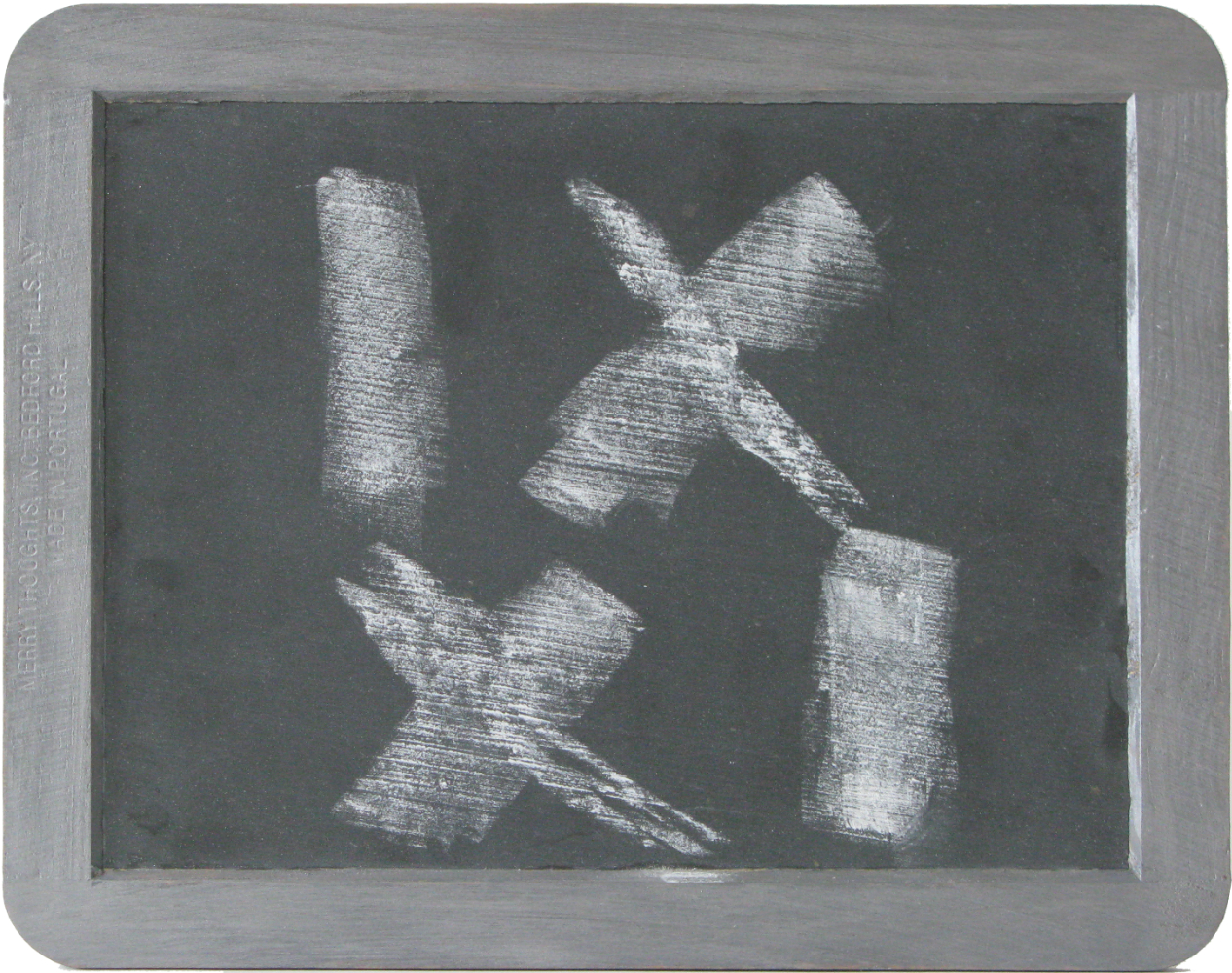

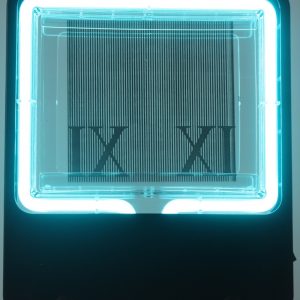

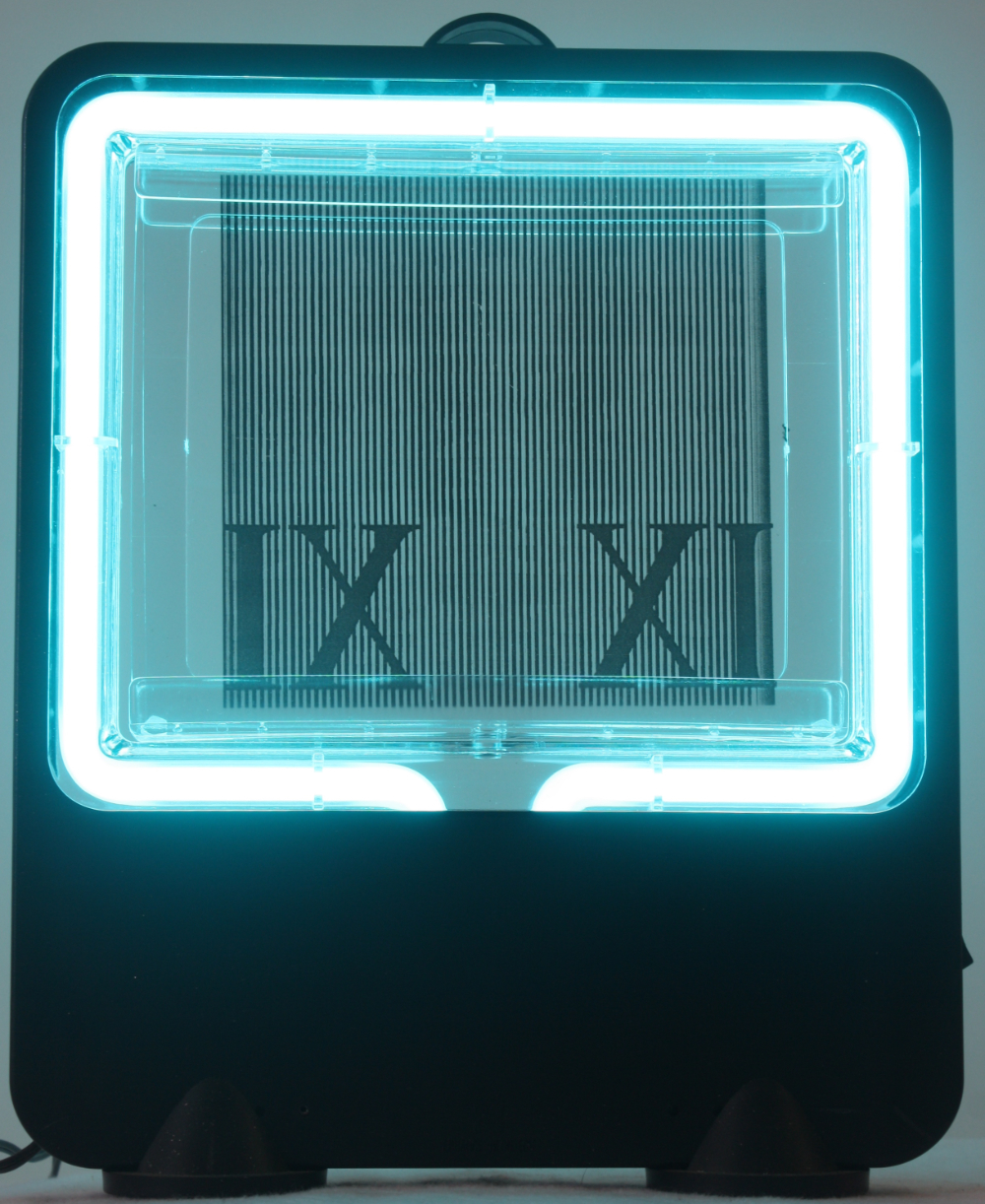

She saw that the image was too loaded for a public piece. “But all my life when I used to do paintings I used to sign with Roman numerals,†she says. “It was to emulate Picasso who used Roman numerals. So I have been playing with Roman numerals for quite a while.â€

It was while she was playing that she came up with

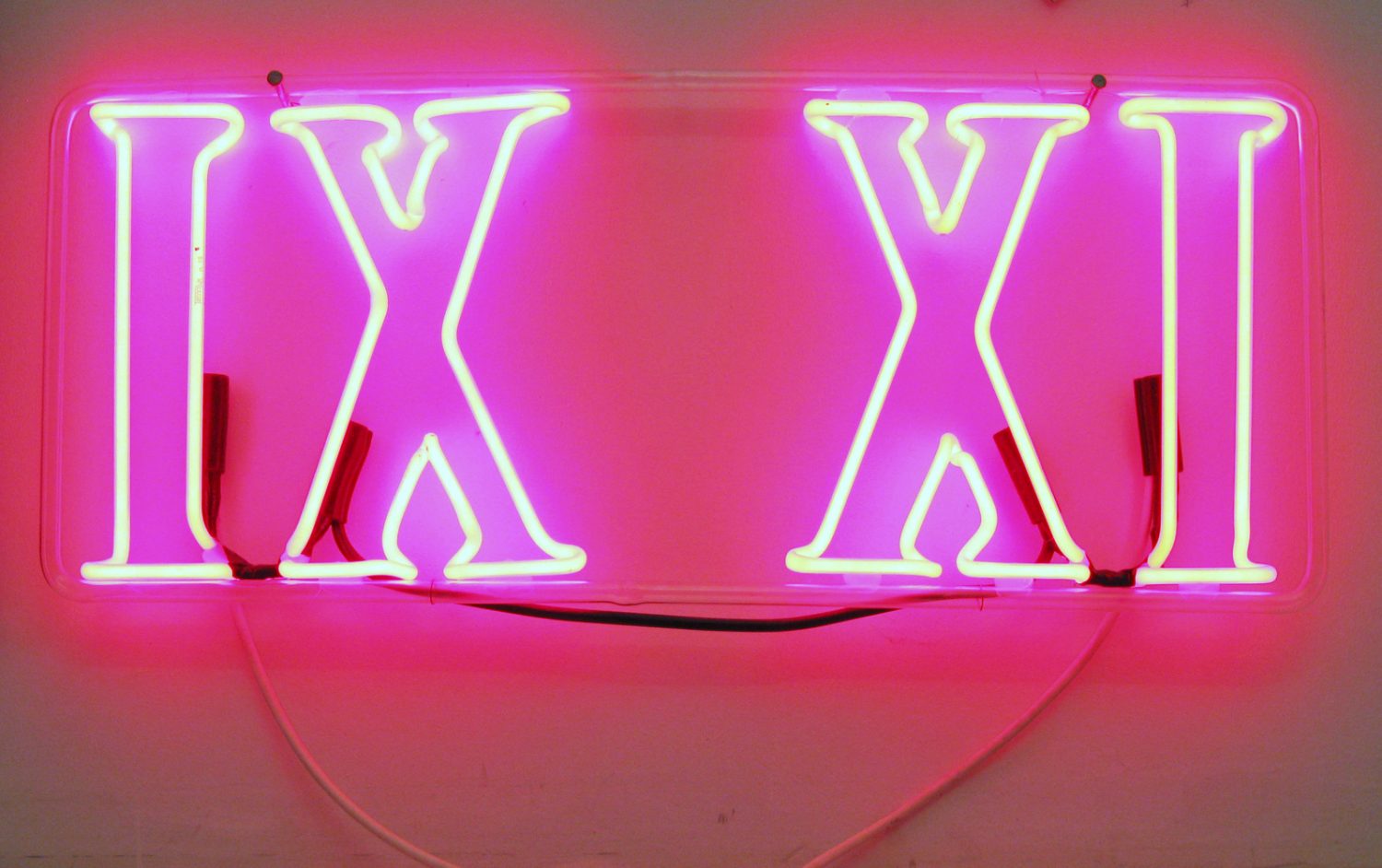

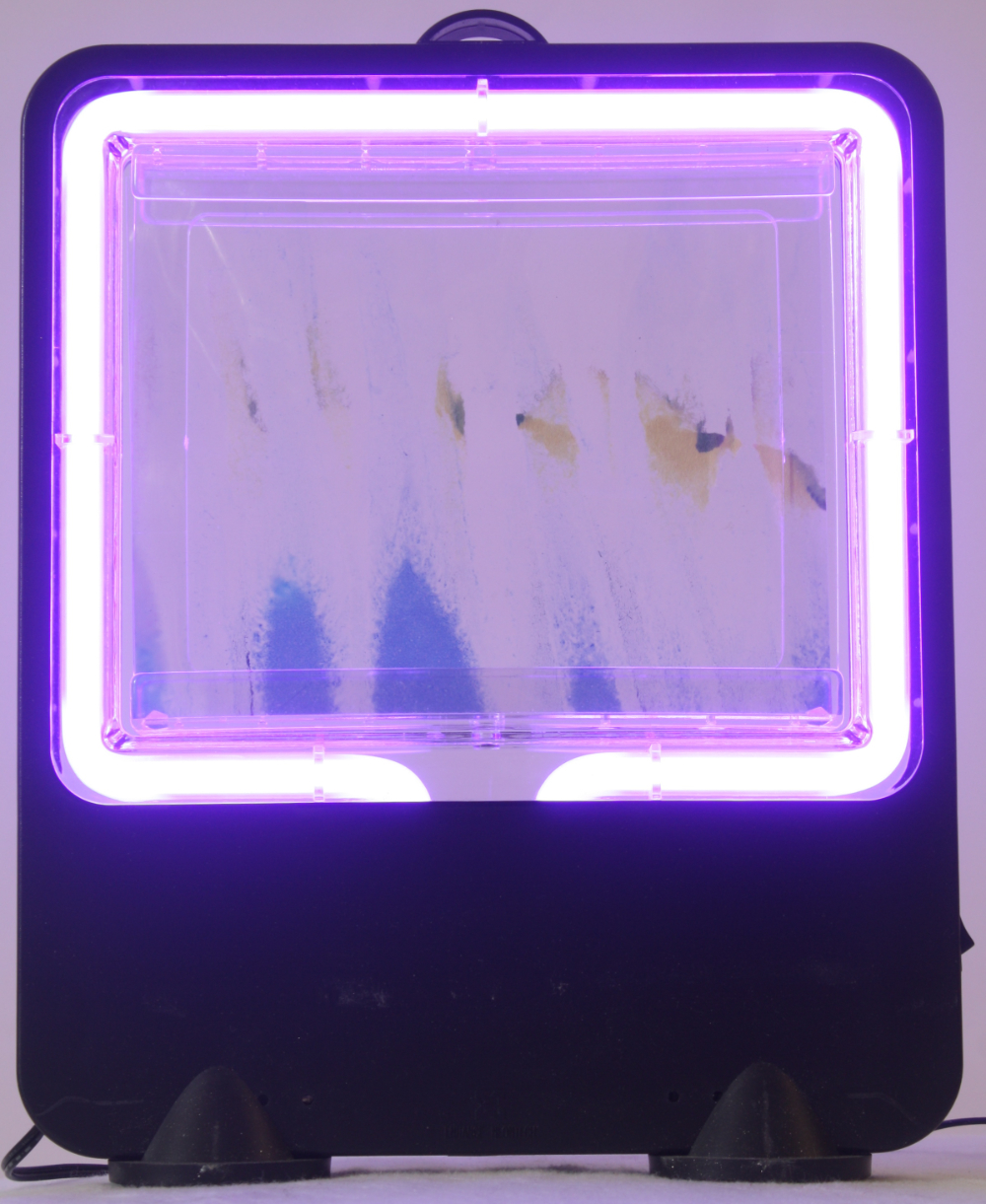

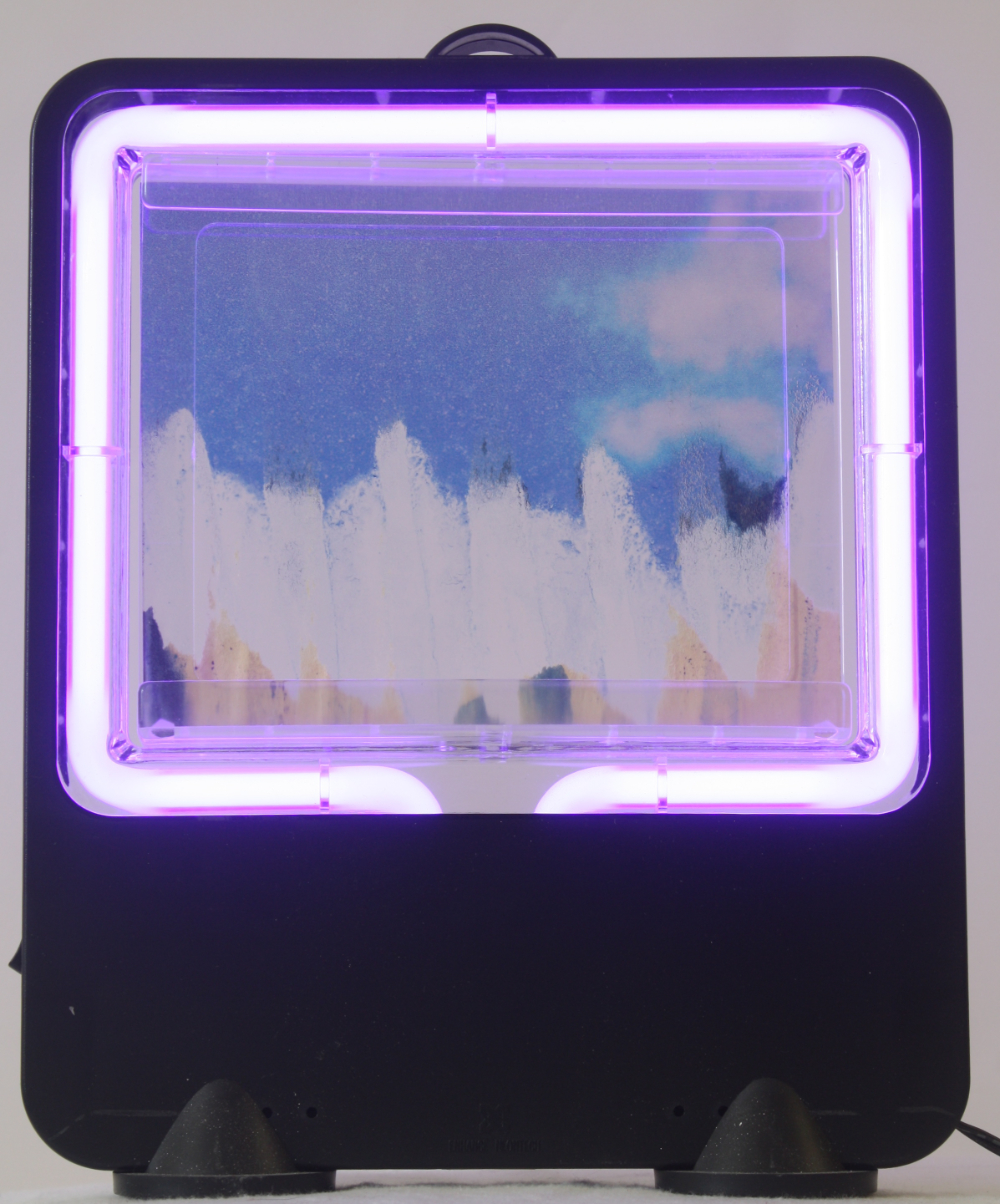

IX

XI

If you happen to be part of that seventy percent of the American public for whom Roman numerals are a foreign country, that means 9/ll. “And that was a palindrome. It was pretty hypnotic.â€

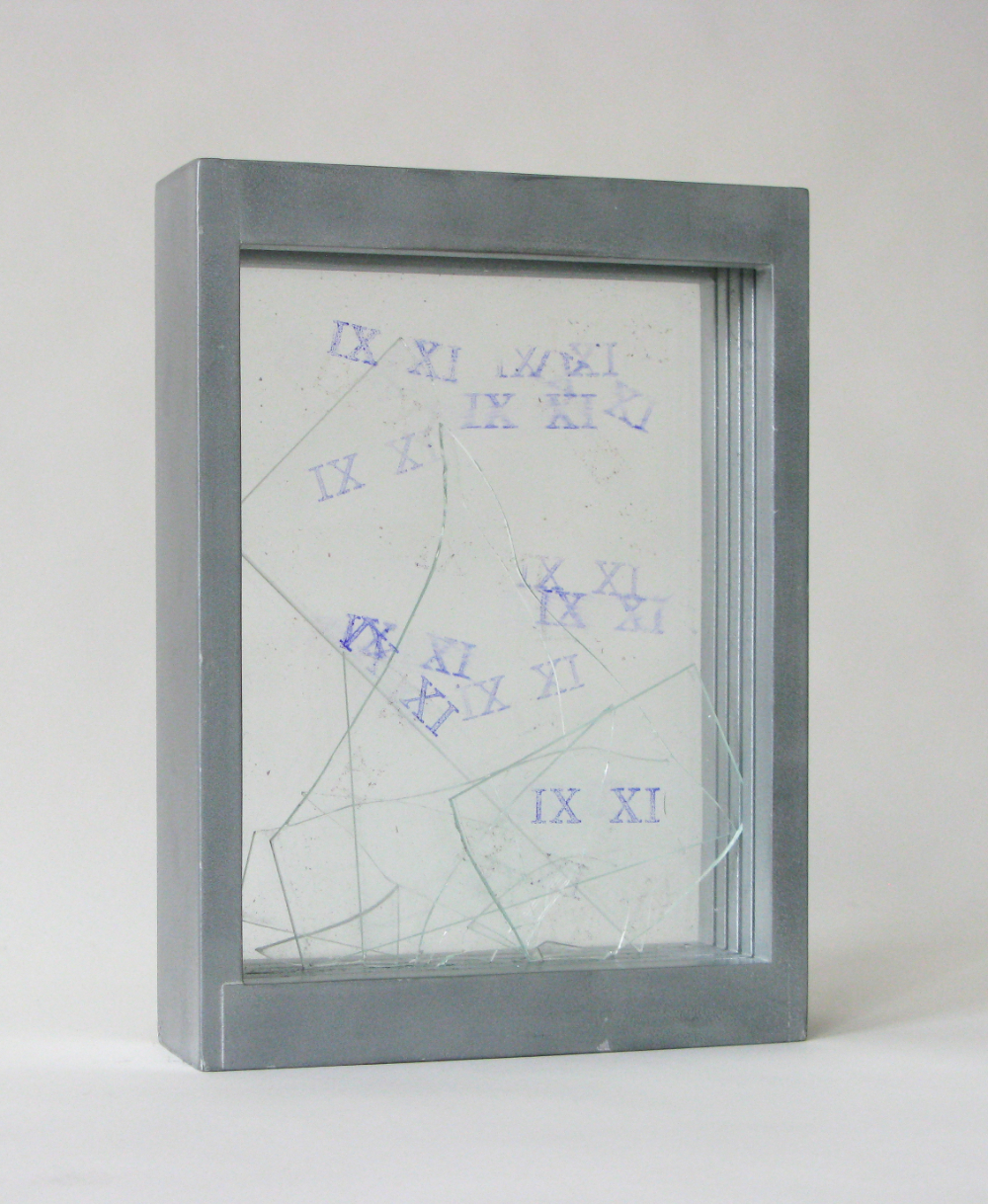

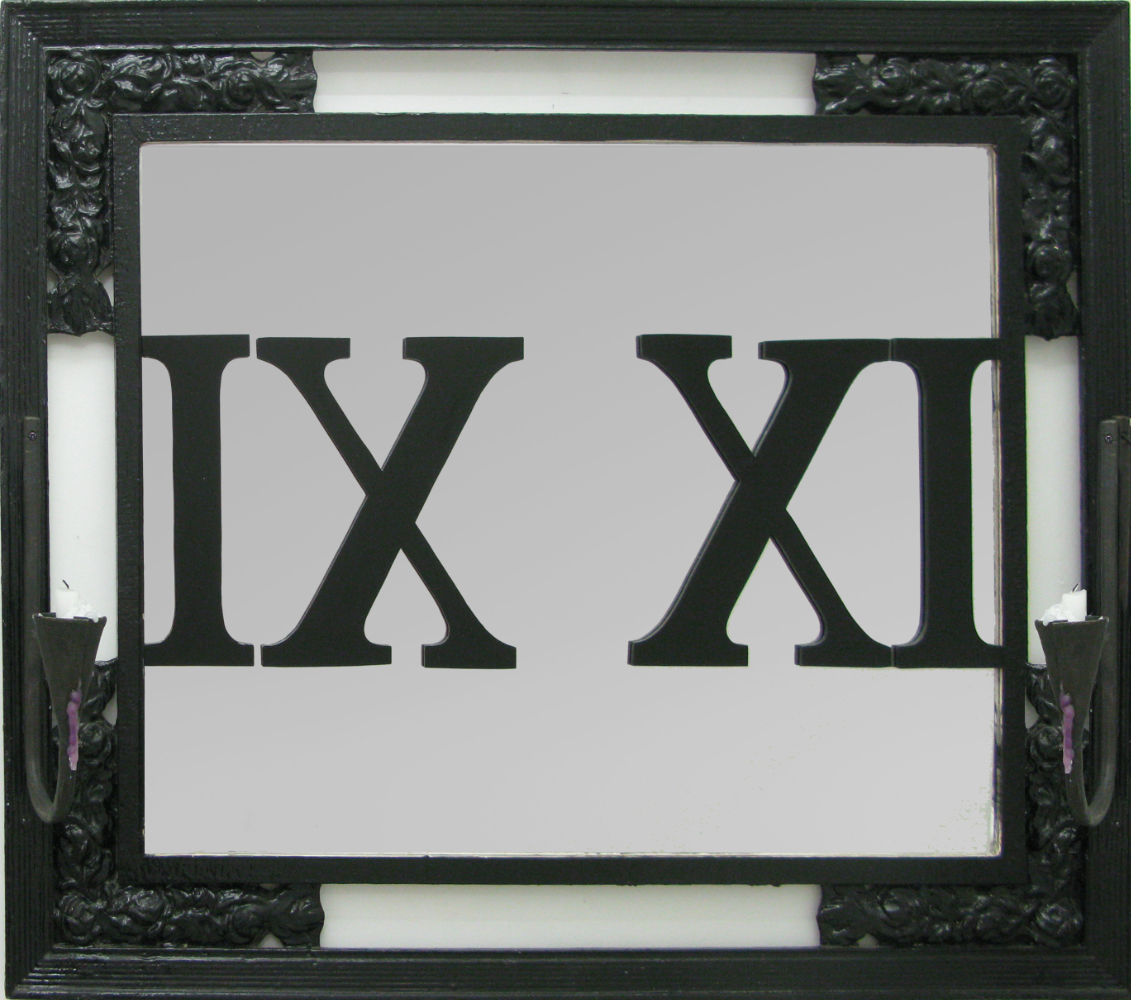

IX-XI is not an aggressive piece. Indeed, it is as abstracted as Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial. She created her own font and, mindful of the example of Robert Indiana, who lost control of LOVE, she has copyrighted it. “I’m going to be copied in China, no doubt. But I wanted to protect myself,†she says, it already exists in several sizes, the largest being a three-footer.

“But it should be monumental,†Ultra Violet adds.†I think it should be as tall as the World Trade Center.â€