It is with great pleasure that the Department of Art & Design and the QCC Art Gallery present the 2015 Queensborough Community College student exhibition. As always, this year’s selection of representative student work offers a wide array of mediums, methods, and content. At QCC, the department seeks to inculcate a mastery of the fundamentals of visual art in every student, in preparation for either more advanced study at a four-year institution or graduate school or for professional practice. As such, we emphasize the foundational techniques and skills for a variety of mediums including painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, video, and digital design.

Students at QCC, like students everywhere, generally practice one of two techniques in the fabrication of their work. Some adhere to a more classical, academic style of working, which most clearly indicates their increasing mastery of the aforementioned mediums. Others, perhaps driven by what the early 20th-century painter Wassily Kandinsky once called the artist’s “Inner Necessity,†move beyond basic technical mastery in favor of a more expressive, personal vision or in some cases more abstract handling of materials in the fabrication of works. In all cases, we see emerging young artists exploring a plethora of techniques and methods and subsequently rendering a profound diversity of visual expression.

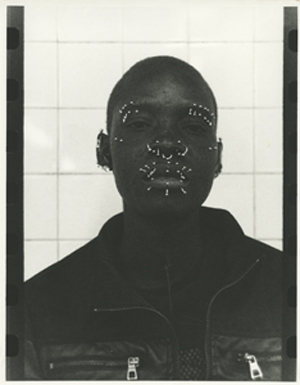

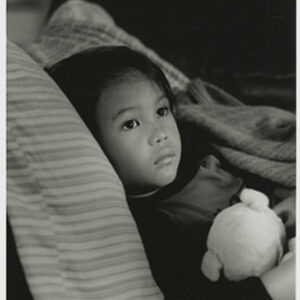

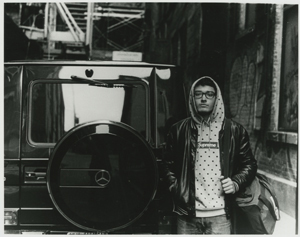

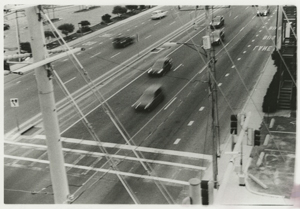

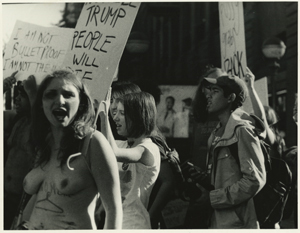

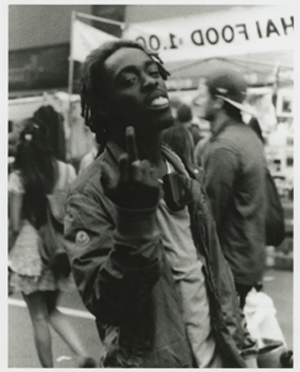

This year, we see a variety of strategies employed by students who are attempting to both master their medium and push farther into the realms of expression and abstraction. With this in mind, one often thinks of photography as a medium of irrefutable truth. In other words, what one sees in a photographic image is commonly assumed to be what was actually there in a given place at a given point in time. Several student photographers grapple with this dichotomy: how does one express oneself or one’s perceptions of the subject via a medium known for its ruthless verisimilitude? The work of CJ Reitman offers us a bold resolution. In her intensely cropped up-close portraits, Reitman gives us what we expect in a photograph: a multitude of visual information defining the contours, shapes, and proportions of the subjects’ faces. But Reitman’s cropping forces us to look deeply into the eyes of her subjects, rendering more than mere surveillance or identification. We see the uniqueness of each individual shine through, something captured by a photographer willing and able to supersede the standard parameters of photographic exchange.

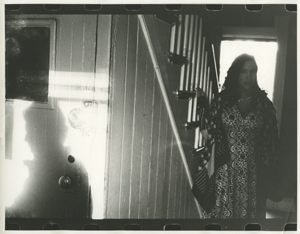

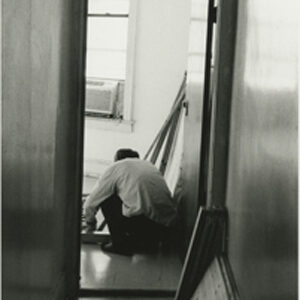

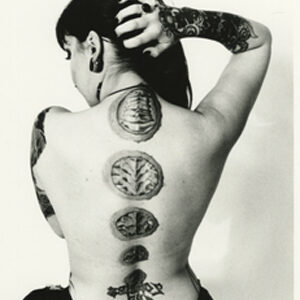

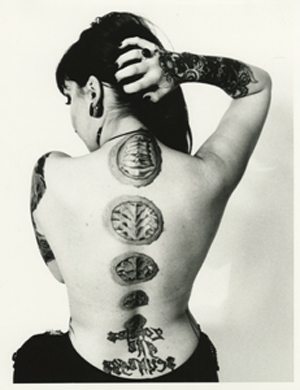

Similarly, Daniel Karlic’s portrait of Laura offers us a striking image, albeit somewhat farther back, of an equally compelling subject. The young woman returns our gaze confidently, brandishing not only her face but the mysterious array of tattoos that perhaps have a deeply rooted meaning in her personal history. Karlic goes further, setting up a provocative geometric composition by placing the woman behind a staircase banister, a trope that offsets and intensifies the contradictory organic forms of his human subject.

In graphite drawing, our students likewise display a variety of approaches to their medium. We see the classically inspired still-life drawings exemplified by the rich, chiaroscuro-drenched work of Min Wen. Wen shows a startling control of the medium, as the image ranges from the nearly white reflective surface of the classical bust to the dark grey tones of the drapery behind it. In contrast, the subject matter and stylistic approach seen in the drawings of Kun Suk Hare and Mariel Torres seem derived from the annals of Cubist fracturing and reconstruction. And yet, the same value scale is at play in the work of all three students.

In painting, Xiaoli Chang warrants mention of stellar brush control and composition, as well as chromatic range. Chang gives us a stately, serene still life ala Georgio Morandi, as each object congeals with the whole composition yet asserts its own individual weight within the representational space. While Chang manages to balance the composition almost perfectly via the placing of geometric form and plane, the chromatic balance is equally as impressive. Notice the boldness of the large bluish-white pitcher in the middle ground, surrounded by reds, yellows, ochers, and browns. Again, we see a student practitioner gracefully balancing organic and geometric lines in a near metaphysical coexist.

Frank Boccio takes the medium of acrylic paint to compositional and formal extremes in his humorous yet claustrophobic Second Avenue Subway. Boccio reminds one of the passionate, childlike renderings of Jean Debuffet and other mid-20th century representatives of the Art Brut movement in Europe. This movement attempted to recapture the childlike innocence of perception and expression via exaggerated lines, bold coloration, and anti-academic cluttered compositions in both painting and sculpture. Thus, Boccio’s work indicates an intellectual bridging of the gap between art historical awareness and the everyday experience of the New York commuter.

This year’s show includes two outstanding examples of student work venturing into three dimensions as well. With Jerry Schiff’s Soaring and Junhao Zhang’s Wave, we have two students who prove the well-known dictum that abstraction of the form may also create beautifully expressive objects, albeit without the aid of aesthetic literalism. Schiff, working in the very difficult and ancient medium of alabaster, something favored by artists dating back to the earliest days of human civilization in Mesopotamia, gives us a powerful study of texture, line, and an alternating emphasis on positive and negative spaces. What is astounding is that Schiff manages this in a relatively compact twenty-inch-high piece. Scale is no barrier!

What I have discussed here, due to the constraints of the format, is only a fraction of the student work on display this year at our college art gallery. There are many more examples of student work that successfully address the issues mentioned above. Please enjoy and by all means pursue your own insights and revelations while viewing.