Realistic Beauty And Painterly Passion:

Manuel Quintana Martelo’s Aesthetic Conflict

by Donald Kuspit

He cannot tell whether she is Beatrice or his Belle Dame Sans Merci. This is the aesthetic conflict, which can be most precisely stated in terms of the aesthetic impact of the outside of the ‘beautiful’ mother, available to the senses, and the enigmatic inside which must be construed by means of creative imagination.

…The tragic element in the aesthetic experience resides, not in the transience, but in the enigmatic quality of the object…. To have aesthetic experiences we must first expose ourselves to ravishment by the external formal qualities of the object. Then we must grapple with our doubts and suspicions about its internal qualities. Since this conflict relates only to the mind of man and man’s products, the great avenue of relief is to expose ourselves to the beauty of nature.

Donald Meltzer, The Apprehension of Beauty (1)

I look at Manuel Quintana Martelo’s works and what do I see: again, and again exemplification of the aesthetic conflict, unresolved yet alleviated, in many works, by poignant attention to the beauty of nature, as the refreshing alternative to the beauty of the female body. Both are transient: the roses in Rose St, 1993-98, Ramiño de rosas, 1996, and Kosovo, 1999 will wilt and die, and the beauty of the young women in A limonoeira de Padrón and Desnudo, both 1996 will surely fade and their flesh sag. But the roses have the ontological advantage of being closer to the heart of nature–more purely natural, more of the essence of nature–and so more memorable than the women. However glorious their bodies they have minds that compromise it, a self-consciousness that “pollutes†their flesh, that informs their being so that it seems peculiarly inaccessible. However physically present they are psychically absent, for they have minds as well as bodies, and while their bodies are obvious their minds are mysterious: we don’t know what they are thinking. Â

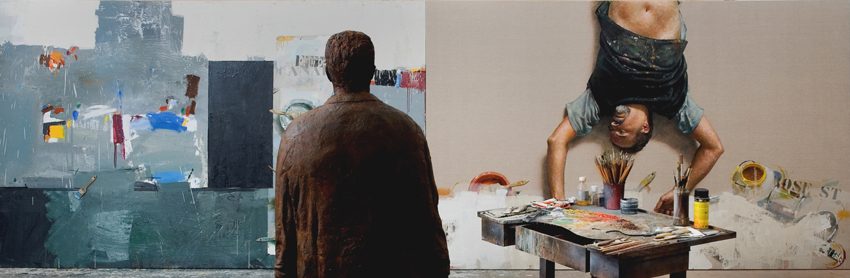

Thus we see Martelo’s nudes from the back, as though they were turning away from us—giving us their backs, as the saying goes, to hide their consciousness from us. We can look at their bodies all we want, but we can never know what’s on their minds: they keep to themselves however much their bodies become artistic keepsakes. We are blind to the inner life of Martelo’s nudes—perhaps their nudity blinds us by hypnotizing us—and indifferent to her as a person, but unmoving and silent—her all-encompassing, ennobling stillness—she preserves her integrity. Holding her own against our voyeuristic presence, she becomes immune to the male gaze. In short, we can possess her body—at least its back—with our eyes, but we have no insight into her soul. Â

In contrast, to see the rose is to have insight into it, to take complete possession of it, for the rose has no secret mind, no mysterious inner life, no self it is conscious of, indeed, no consciousness at all. It hides nothing: it doesn’t turn its back on us. There is no difference between its inside and its outside; it’s beautiful outside unfolds its material inside. Martelo’s rose is a traditional symbol—it is the familiar token of tender love in a world of tragic suffering, as From Schindler’s List, 1992-1995 and Kosovo make eloquently clear—but it does not need to be one to make its existence felt, to have existential purpose, to be profoundly meaningful: for the rose, to exist is to be inherently meaningful. If “ripeness is all,†then Martelo’s exquisite rose epitomizes the ripeness of existence, making it doubly ripe with meaning.

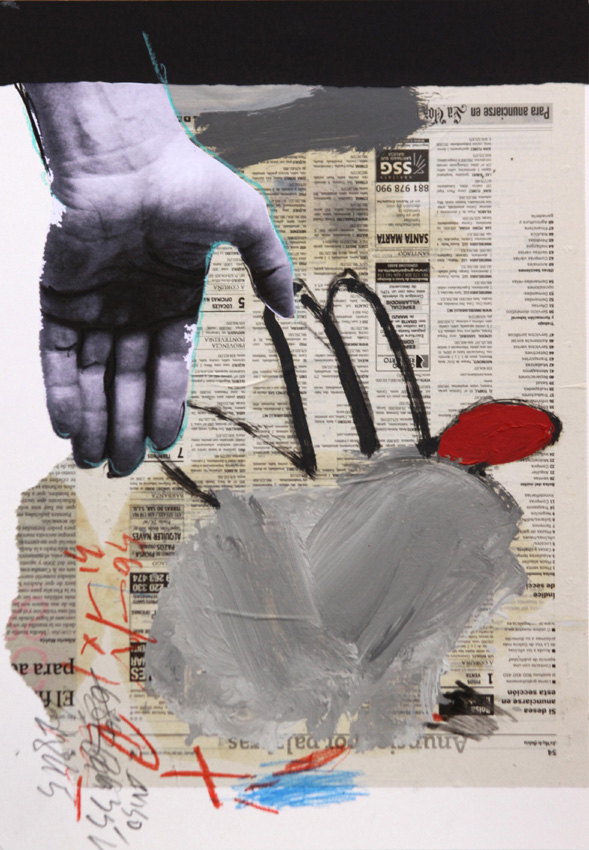

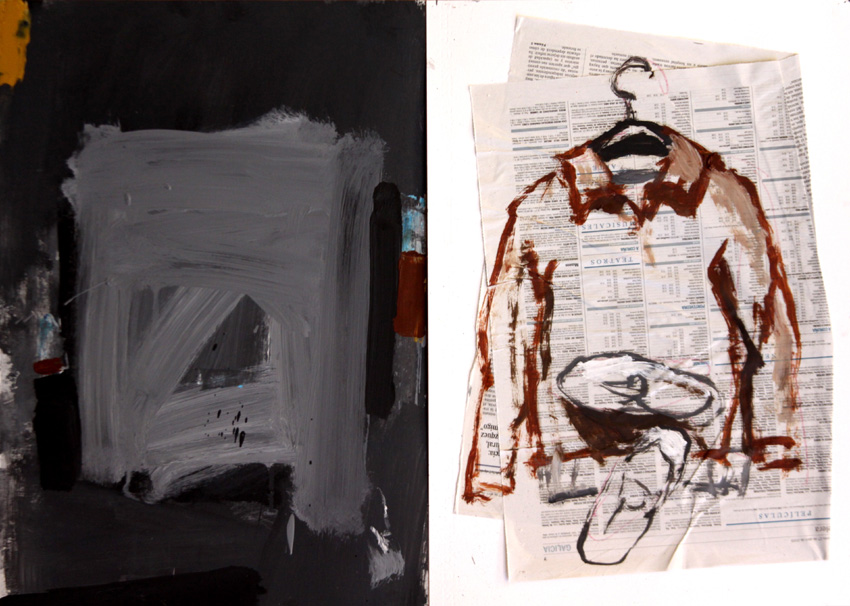

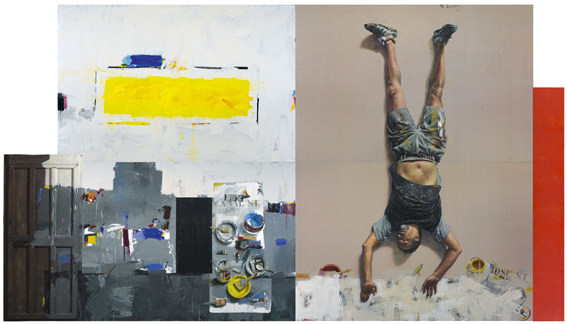

But I have talked about relief from aesthetic conflict by turning to natural beauty, not the way aesthetic conflict manifests itself in Martelo’s art—repeatedly and compulsively, as though he cannot resolve it, however hard he tries, suggesting that it is an incurable human condition. One can escape it by turning to nature, but one’s own nature—the conflict between one’s instincts and the real objects towards which they are directed—remain permanently unresolvable. It is by way of juxtaposition that Martelo proclaims the universal conflict between internal reality and external reality or, as Kandinsky put it, between internal necessity, driven by instinctive, often unconscious feelings, and external necessity, involving consciousness of objects that are “not me,†impersonally “hard facts†that may become personal if they are “heartfelt†but remain indisputably “alien.â€Â Martelo presents the discrepancy between psychic and social reality—between subjective expression and objective datum–without trying to reconcile them, perhaps because to do so would make each into a shadow of the other, neutralizing the presentational power and experiential significance of both, and perhaps above all obscuring the uncanny beauty and cognitive integrity each has when it appears by itself, as though a realm unto itself.

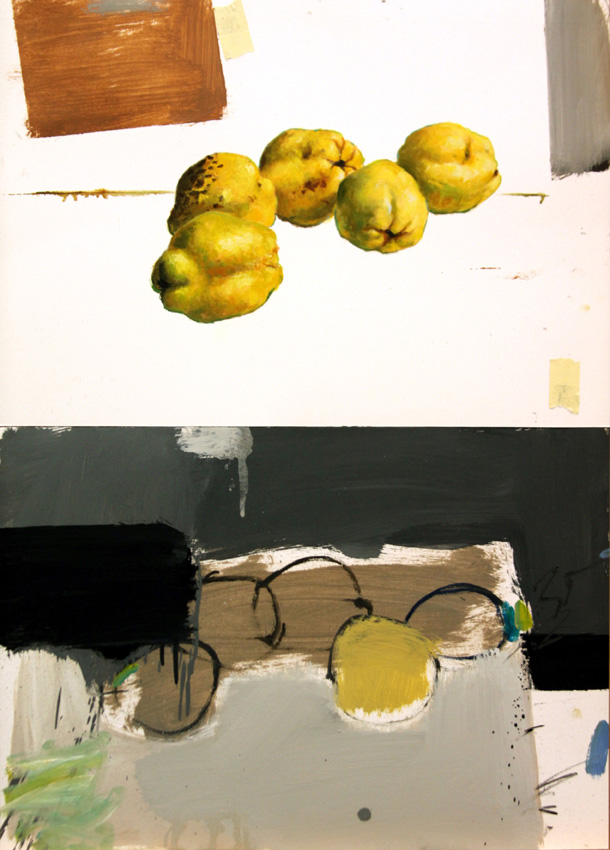

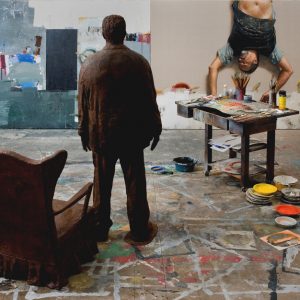

Thus, we have, side by side in the same studio space meticulously rendered traditionalist still lives and emotionally urgent modernist painterly surfaces. (Martelo never seems to venture out of the studio, however aware of events beyond it, suggesting that however insular he remains conscious of the impingements of history, as his socially aware works indicate.) It is as though Martelo is inviting us to compare realism and abstraction—careful observation of objects (including paint tubes and paint brushes, the objects of his craft), giving them a certain dignity and autonomy, and grandly pure expression—without asking us to decide which is more convincing than the other. Both are necessary if painting is not to die, as theorists who think it is historically passé argue it has: painting must embrace the contradictions of its history to remain vital. Â

Variable I, 2003 makes the point decisively: a still life of paint brushes and paint tubes, both contained in pans, with a single flat brush between them marking the flatness of the all but pure white surface on which they are displayed, is juxtaposed with a Rothkoesque abstraction composed of planes of differently toned green. Which side of the diptych is preferable to the other? There is no answer, which is the “post-modernistâ€â€”and “post-traditionalistâ€â€”predicament. The opposites are paradoxically together if not united, suggesting that cognitive and perceptual dissonance have become uncannily consonant in the contemporary situation of painting, making for a more intriguing, provocative esthetic experience than traditional painting and modernist painting can offer individually. The friction generated by their juxtaposition de-reifies them—both traditional and modernist painting have become over-objectified in the current “post-historical†situation, in which the idea of a progressive, so-called linear development of art has collapsed under the weight of its own simplicity—by dialecticizing them, suggesting that they are unwittingly parallel lines that meet unexpectedly in esthetic infinity.    Â

The great majority of Martelo’s works are bodegons, as Bodegón con plátanos, 2000 and Bodegón 29 de maio, 2007 make clear. Sometimes the still life objects are colorful fruits of organic life, sometimes the inorganic debris of materialistic society, often juxtaposed in the same picture–the former on a table, the latter on the floor—as though to show the parity of life and death and their intimate relationship, even ironic interchangeability. There are many everyday objects, such as sneakers and umbrellas, sometimes in suggestive relationships, as in Dous paraugas, 2001, where one umbrella is a man’s, the other a woman’s, “surreally†connoting sexual intercourse. But the key to Martelo’s bodegons is not the relationship between the still life objects, however evocative that may be, but the provocative relationship between them and the painterly ground on which they rest, a tension that suggests they are in aesthetic conflict—the dynamic painterliness represents the artist’s mood swings and the static objects the world of everyday life. Â

If Martelo’s still life objects appeared in a featureless, neutral space, like mirages in darkness, as they often do in traditional bodegons–the sense of loss and absence implicit in the blank and black emptiness supposedly gives the isolated objects an excruciatingly immediate presence—rather than in the context of an “abstract expressionist†ground as physically poignant (if dimensionally different) than the still life objects, then Martelo’s paintings would no longer be effective as emblems of aesthetic conflict. If Martelo was only a realist or only an abstractionist, however aesthetically subtle his realism and abstractionism would undoubtedly be, his art would be an imaginative failure because it would not convey aesthetic conflict. Â

The ability to tolerate aesthetic conflict requires what Keats famously called “negative capacity,†and Martelo has it, which is perhaps the ultimate reason he creates major art. His juxtapositions or “undecidability,†as it is fashionably called–his knowing “duplicity†or double vision, confirming Baudelaire’s idea that the creative artist is necessarily a “homo duplexâ€â€”show that he can tolerate uncertainty, that it can open the way to a new synthesis of old ideas, thus refreshing art. Uncertainty can catalyze his creativity if he patiently accepts it rather than compulsively reaching for the truth of art—always a vain Sisyphean effort– rather than waiting for it to spontaneously reveal itself aesthetically. Â

Dogmatically elevating abstraction at the expense of realism or vice versa—regarding one as authentic, aesthetically self-illuminating art and the other as aesthetically inconsequential art—destroys the possibilities that arise when one allows oneself to remain suspended between opposites, allowing them to ripen into an aesthetic revelation of their unity: the revelation of their oneness that Kandinsky had when he equated the “great abstraction†and the “great realism,†“two paths, which lead ultimately to a single goal,â€(2) as Martelo’s art shows. It is hard to say whether it is realistically realized abstraction or abstractly realized realism. Â

I think that when Martelo places a three-dimensional room next to a two-dimensional image of the same room he is exposing us to the aesthetic conflict between what psychoanalysts call the passionately imagined world of internal objects and the realistically observed world of external objects, implying that the difference between them can be bridged, but finding it hard—seemingly impossible—to build the bridge, for the imagined internal objects have their own agency and do not exactly correspond to the observed external objects, which have no agency unless art uses them to create the illusion that they do. Even Martelo’s female nudes lack agency, as their passivity, not to say inertness, implies, and his male friends, portrayed in sketches, also lack agency, however pensive as well as passive they may be. It is not always clear whether Martelo’s still life object is a Beatrice or a Belle Dame Sans Merci, since his expressive painterliness conveys feelings in enigmatic process, and this neither completely dominates the object, transforming it into an inspiring muse—like Martelo’s marvelous lemon, its brilliant yellow apotheosized into an aesthetically pure phenomenon, as though it existed abstractly rather than actually—so that it loses its banality and familiarity. But the lemon is, after all, just another lemon, however purely beautiful. Â

The problematic of the aesthetic conflict, and the ambiguity towards the object it gives rise to, is already implicit in Das Tres Gracias, 1987, a pivotal work. The bodies of the graces begin to fragment and disintegrate, losing their sacred beauty—the gracefulness that is the aesthetic ideal, and that the female figure proverbially embodies–because they are slowly but surely being despiritualized, not to say desecrated, by Martelo’s modernist artistic process. Its abstractness supposedly has its own spirituality—supposedly makes the object more spiritual than it would otherwise be, as seems the case in the bodegons—but here it is subversively physical and disenchanting.  Â

Martelo’s works tell the story of his own art-making, invite us to become a participant observer in the process, to enter his studio and share his paint brushes and tubes of color, and follow his eye as it registers the very particular texture of very particular objects, not missing the slightest sensuous detail, treating each and every sensation as though it was the nuanced essence of the object, and finally experiencing an aesthetic epiphany in which the observed object seems to transcend its own existence even as it becomes more existentially real and precisely observed than it would ordinarily be, indicating that pure sensuous experience can afford a profound “real-ization†orÂ

“re-concretization†of being. At the same time, Martelo’s art makes a general statement about the perplexing aesthetic conflict every artist must experience and address—personally suffer and imaginatively endure–if he is to become a serious artist, and taken seriously, as Martelo must be.    Â

Â

Notes

(1)Donald Meltzer, The Apprehension of Beauty:Â The Role of Aesthetic Conflict in Development, Art and Violence (Old Ballechin, Strath Tay, Scotland:Â Clunie Press, 1988), 22, 27, 157 Â

(2)Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo, eds., Kandinsky:Â Complete Writings on Art (New York:Â Da Capo Press, 1994), 242