The Dynamics of Norman Gorbaty

by Donald Kuspit

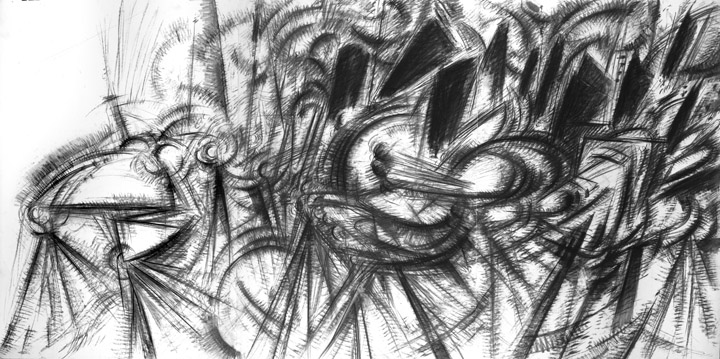

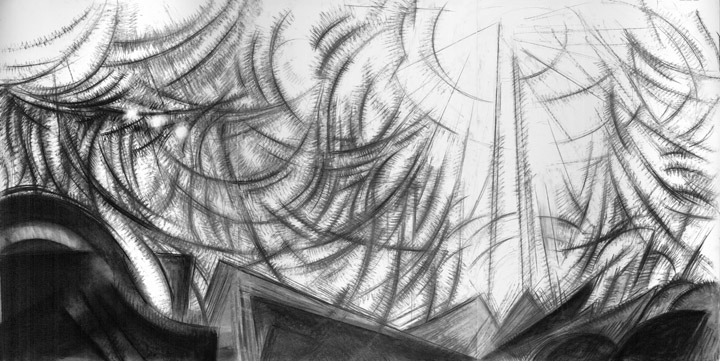

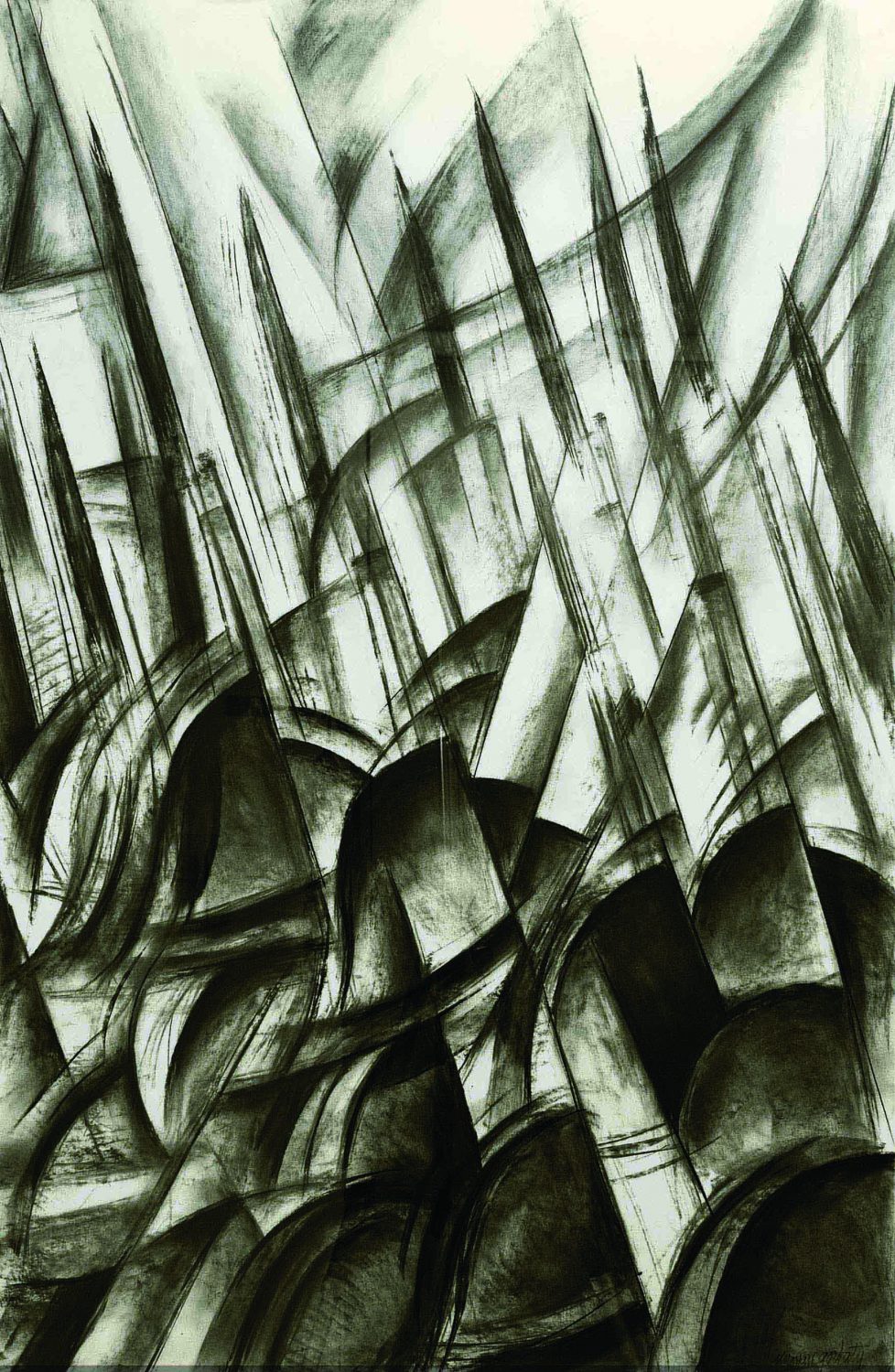

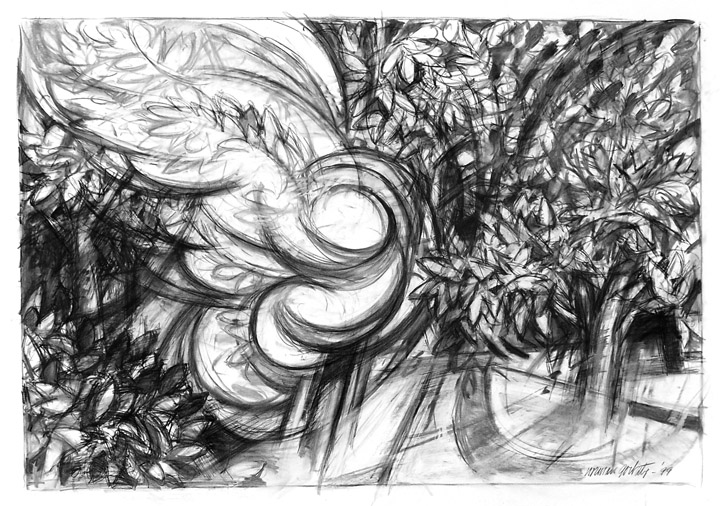

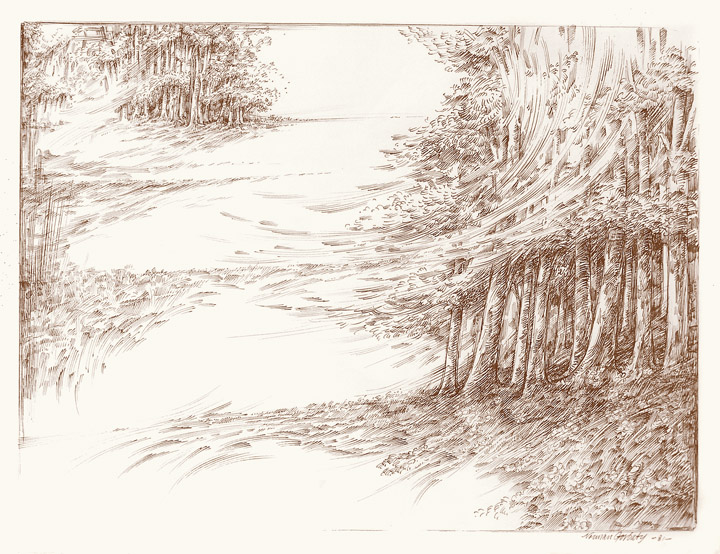

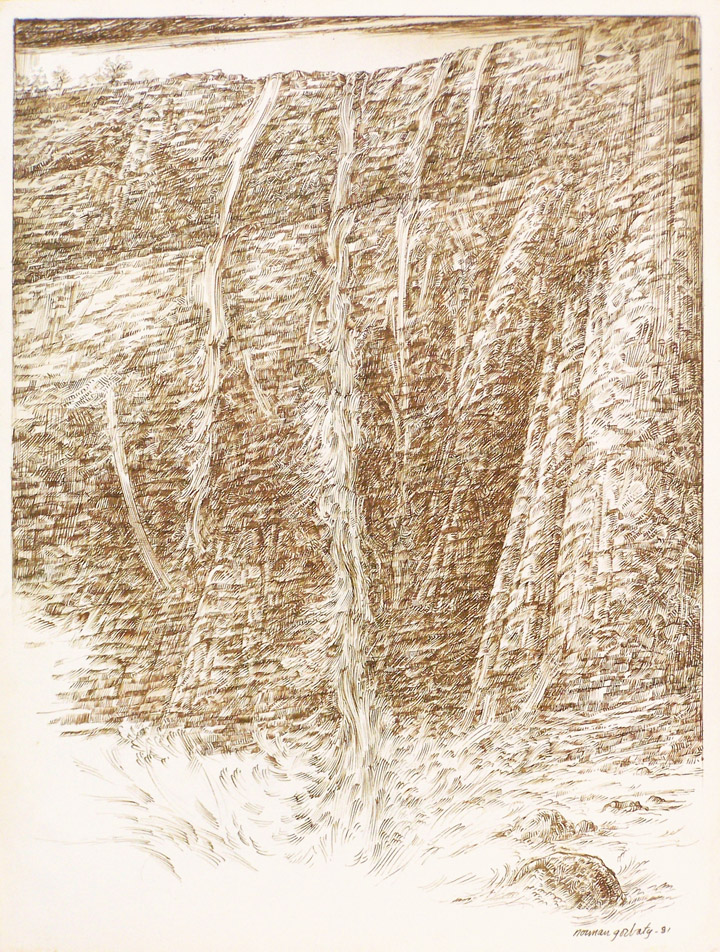

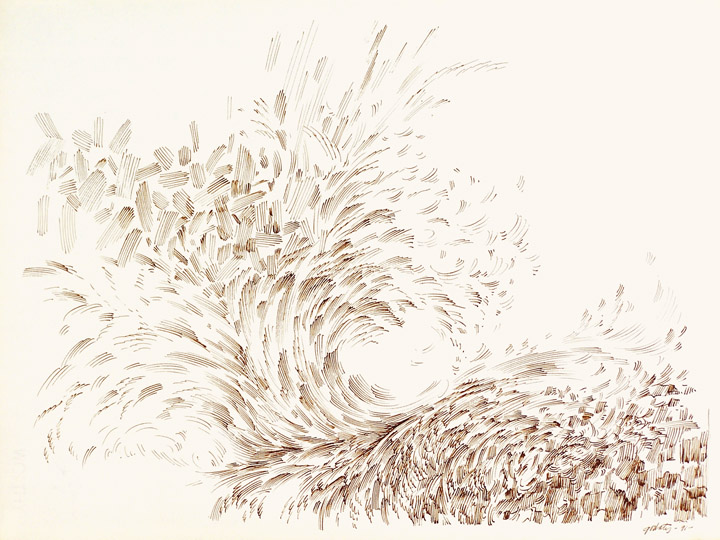

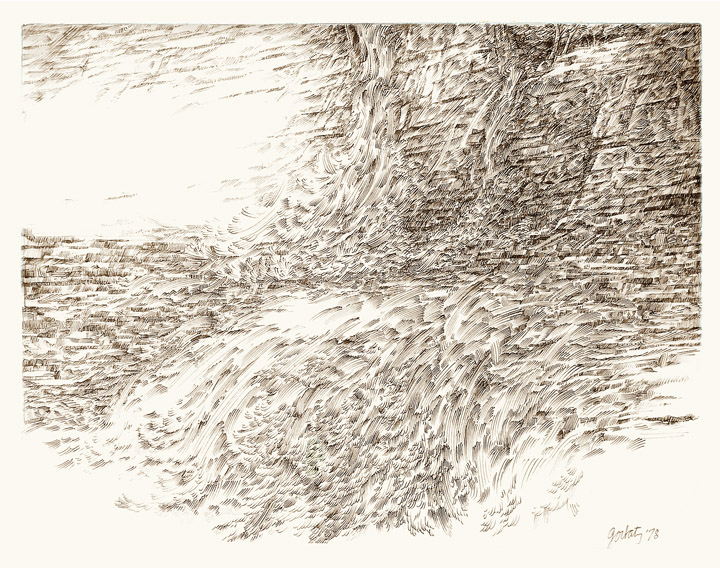

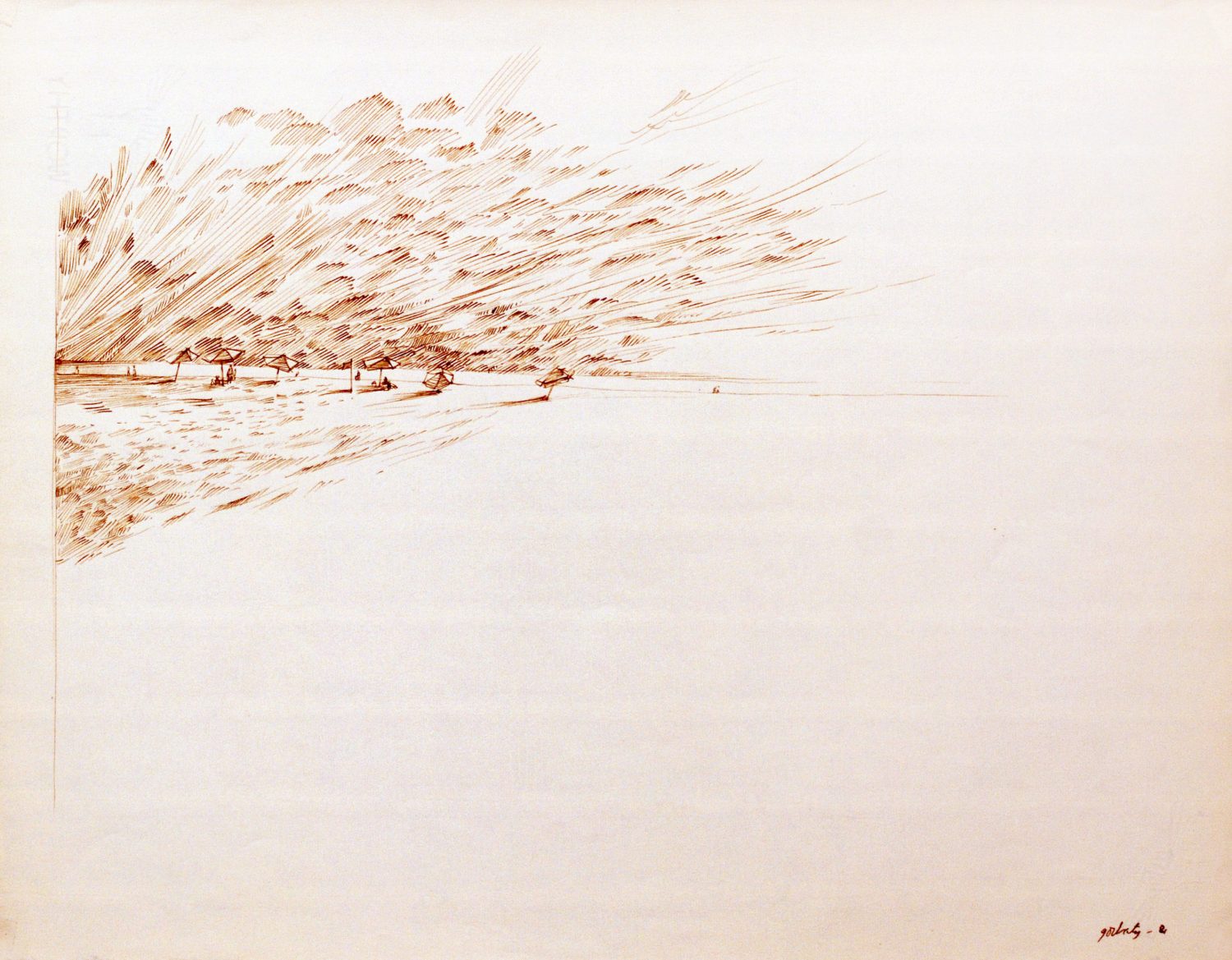

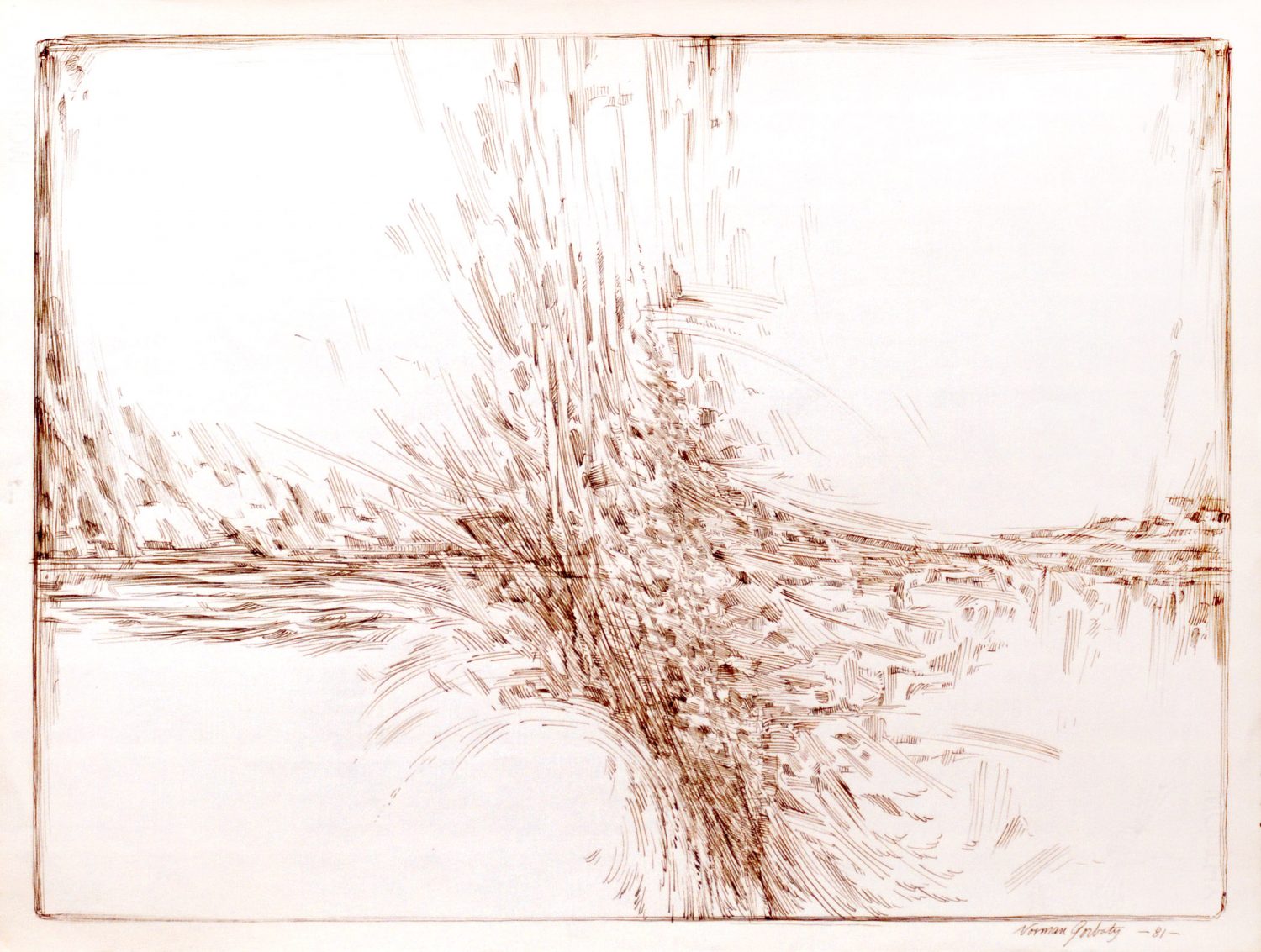

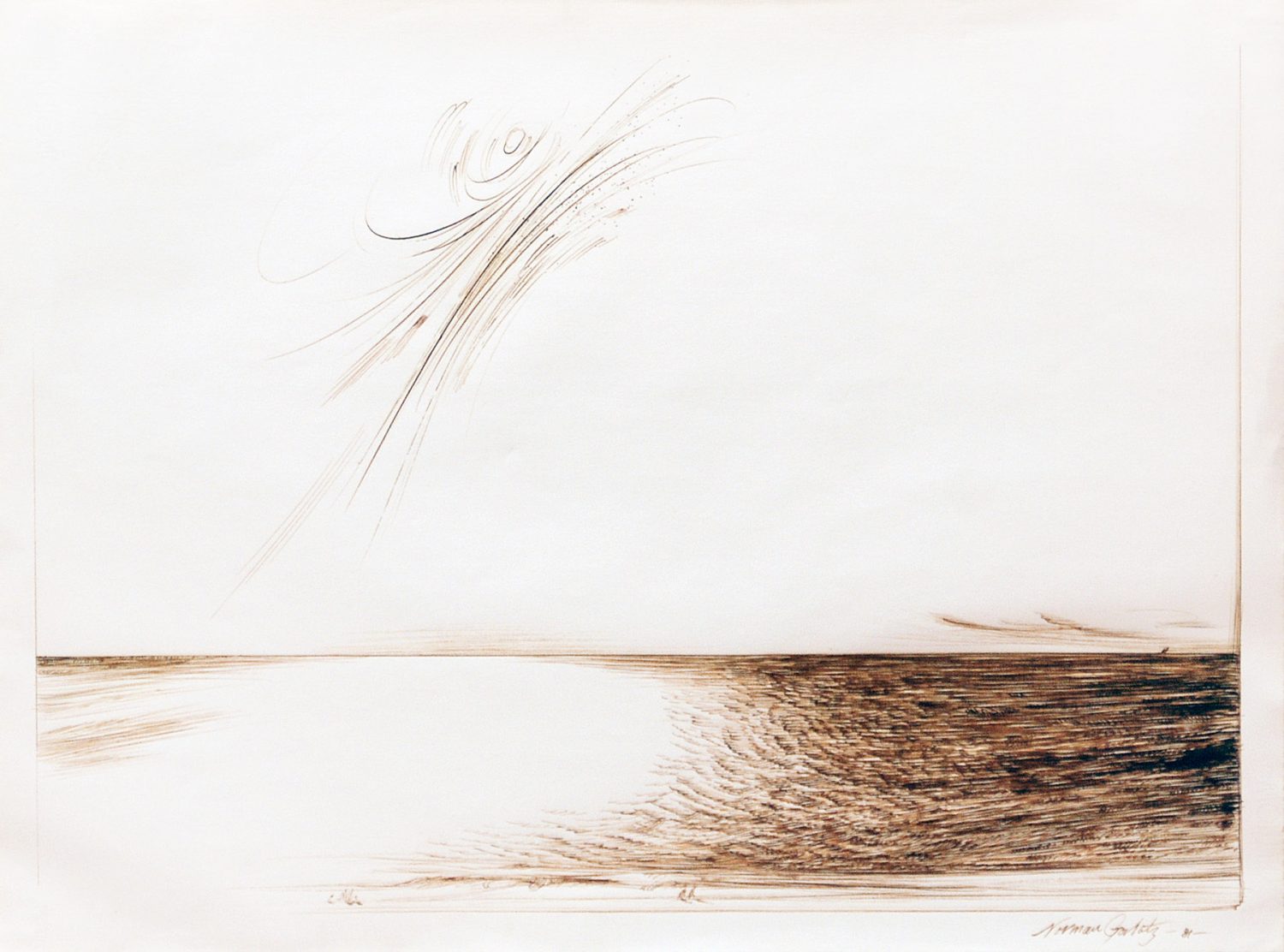

Perhaps the dynamics are most evident in Gorbaty’s stunning images of waves, pen and brown ink drawings in which he depicts, with amazing verisimilitude, their sweeping movement. He seems to capture them at the moment they crest and break, when they’re an intricate conflation of centripetal and centrifugal forces, in Wave No. 1 more the former, in Wave No. 2 more the latter. Gorbaty’s waves have the same contradictory dynamics as Leonardo’s whirlpools: his drawings are more than a match for Leonardo’s, both in their excruciating sense of detail and power of concentration. Gorbaty’s drawings are as cosmically scaled yet as intimate as Leonardo’s. His rapidly flowing water is charged with the same sense of ecstatic turbulence and hypnotic sublimity.

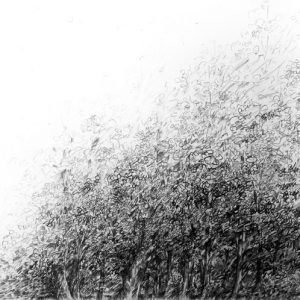

But there’s a major difference: Leonardo is a naturalist empiricist, Gorbaty an abstract empiricist. Art, after all, has changed: Gorbaty is a keen observer of nature, but he’s also a purist. His drawings read as an accumulation of nuances, grouped in an abstract pattern resembling hatching—the short, tensed strokes, each a sort of extended touch, curved like little bows, that form the brisk waves, are tell-tale signs of its momentum, exquisite gestures that seem to explode from its mysterious depths, dissipating in ripples as they rise to the surface, without losing their strength—as well as uncannily accurate representations of a familiar natural phenomenon. Waves are familiar only to the ordinary eye; to Gorbaty’s extraordinary eye, they are demonic and angelic at once—altogether uncanny. They express the ruthless power of elemental nature, made all the more expressive by the power of Gorbaty’s hand. Its swiftness keeps up with the swiftness of the elemental flux, mastering it in the act of identifying with it—a triumphant rather than submissive identification. Gorbaty’s sure and sensitive touch surfs the waves, navigating their undertow to a safe artistic landing. He is as sure-eyed as a good surfer is sure-footed, and the purity of his touch intensifies the waves he sees all around him—for he immerses us in the boundless sea, suggesting what has been called an oceanic feeling–even as it makes the intensity immanent in the current that rhythmically moves the waves manifest.

It is the pursuit of purity—the will to pure form—that enables Gorbaty to render nature with such consummate mastery. He exposes the pure form implicit in its raw matter, paradoxically giving it a refined presence, which even more paradoxically makes it a lived experience, charged with the fullness of being it never has in everyday observation, naively taking appearances for granted. From the beginning, abstraction meant superior consciousness of nature, as Kandinsky and Mondrian argued: consciousness able to abstract its core dynamics from its appearance, resulting in pure art and existential truth. Gorbaty’s images of nature are pure art, however “impressionistic†they may seem, reminding us that Impressionism was in fact the prophet of abstract art, as Kandinsky said. I suggest that the empty areas in Gorbaty’s drawings are emblematic of pure consciousness, indeed, paradoxically embody it, giving them a depth of meaning they would not otherwise have. Gorbaty’s deployment of emptiness gives the drawings a fullness and beauty they would not have if they were simply descriptive. Or if the empty areas were filled in, technically finishing the picture, but leaving it emotionally unfinished. If ripeness is all, Gorbaty finds expressive and formal ripeness in emptiness. No horror vacui for him, but rather emptiness as a symbol—even proof–of enigma. The rare ability to make esthetic use of empty space—to make empty space seem full of mysterious meaning—to make the paper’s blankness evocative of the unseen, the inevitable incompleteness of seeing, even of the permanently invisible, function as pictorial space flooded with sublime light, pure whiteness—is the sign of a true drawing master.

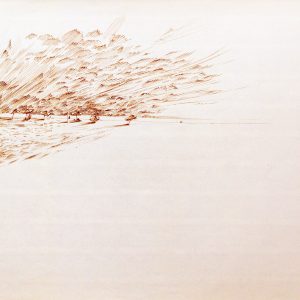

There may be an apocalyptic wind blowing in Olive Trees and Stranger, but the telltale signs of their aesthetic purity are the large areas of untouched paper, paradoxically transformed into experienced space because no line has darkened their whiteness, bringing it down to earth. If they were filled in with detail—even the finest detail of which Gorbaty is capable–the drawings would be less esthetically consummate. Transformed by being untouched, the vacuums of space give Gorbaty’s drawings ethereal freshness, beauty, and profundity, making them masterpieces rather than mere records. They acquire an abstract aura epitomizing the dynamic core of nature. The fluidity of Gorbaty’s handling adds to the wind’s fluidity, convincing us that we feel it in all its immediacy, as he does. Trees Up, Florence, Paris, Rome, and Landscape Venice make particularly daring use of the pellucid whiteness of the paper. It conveys the enormous space encapsulated in the picture, as well as the light flooding the space, so that it seems the space of the sky. So blinding is the light in the emptiness that the trees and buildings reduce to incidental shadows, sketchily nuancing it with their “touchiness.â€

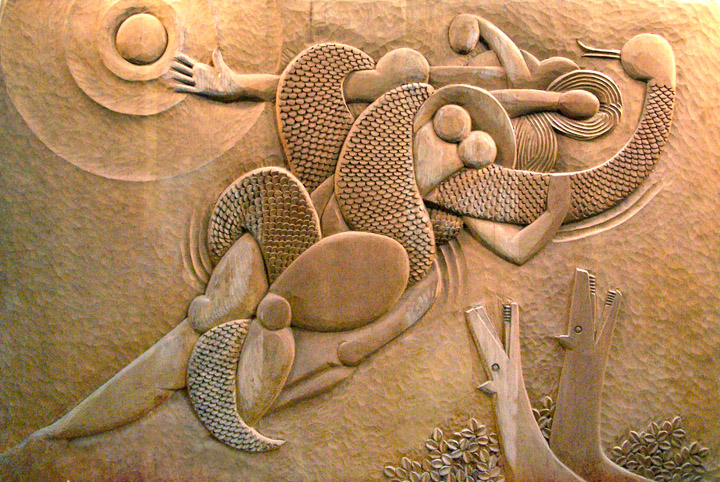

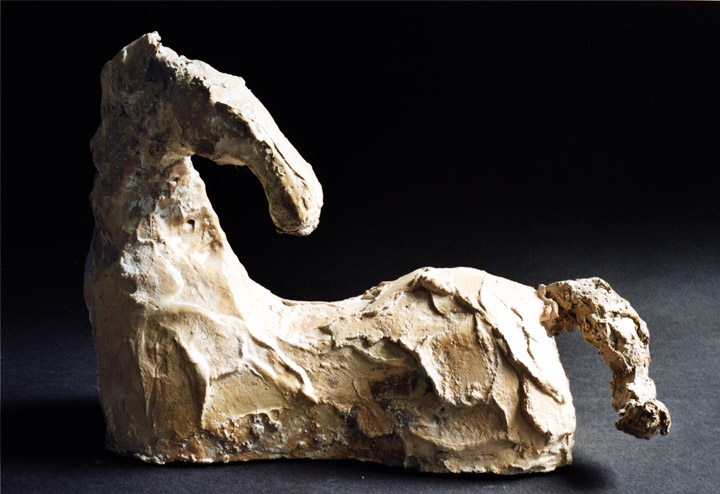

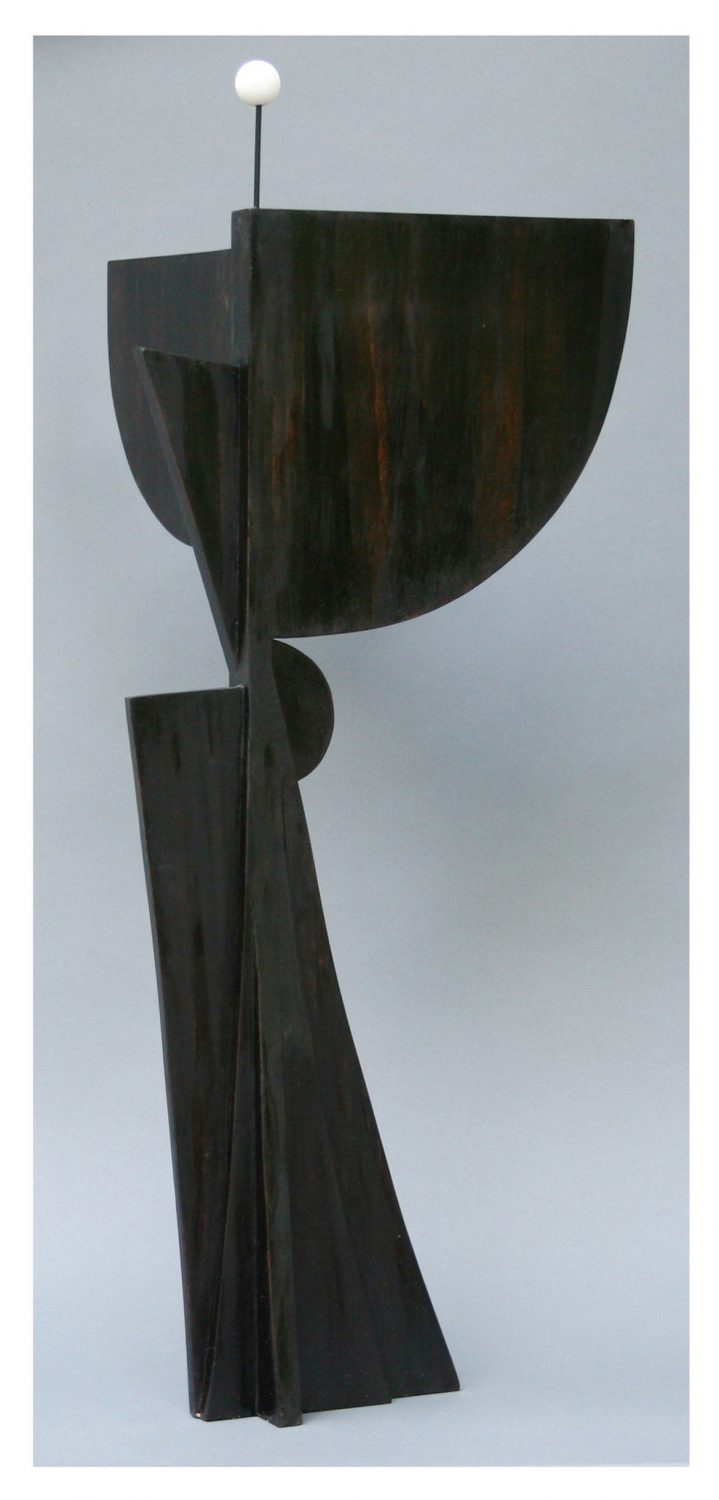

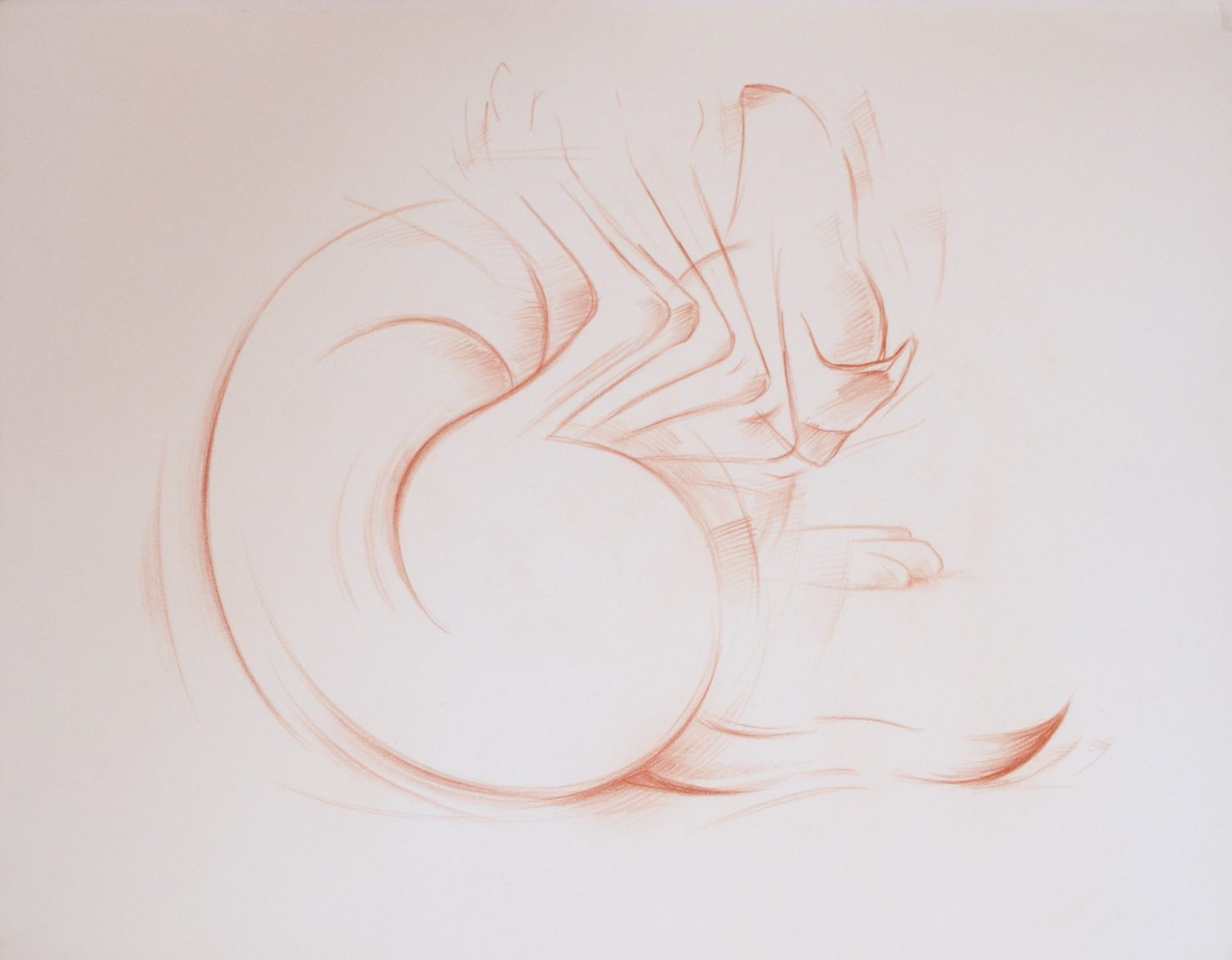

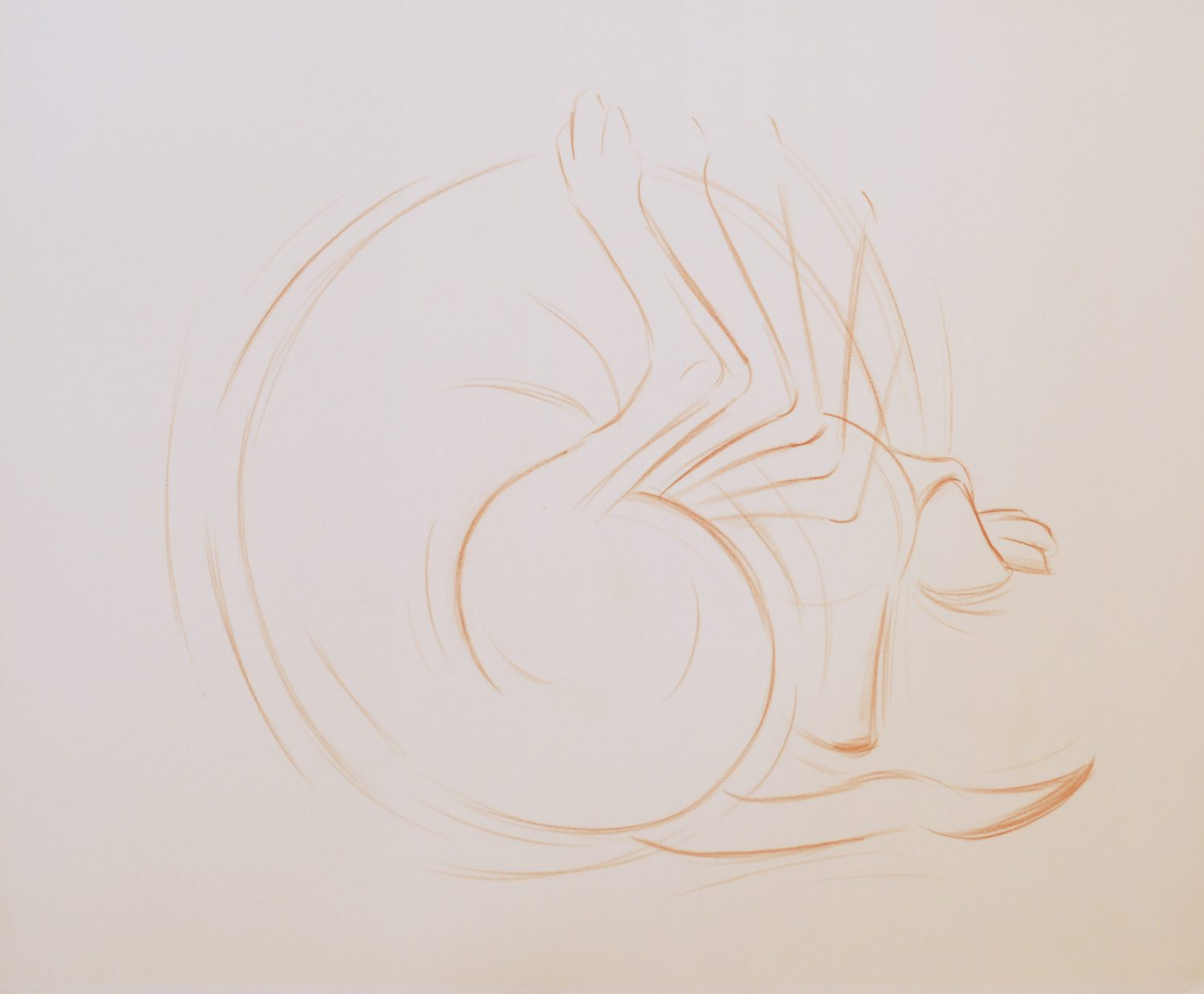

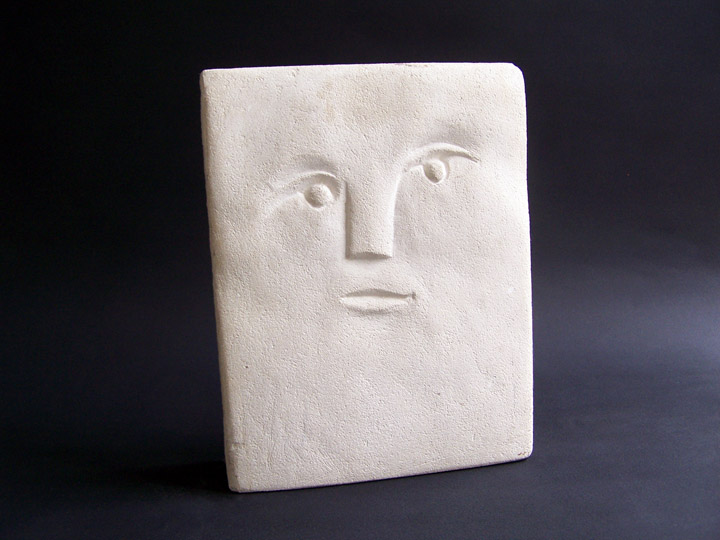

Gorbaty is a master of movement, and there is nothing more “moving†to him than the female body, an “expression†of nature irresistible by reason of its complex dynamics. Instead of being straight up and down, like the male body, it is alive with curves. Gorbaty works in wood; such free-standing sculptures as Female Nude, Modern Dancer, and Spanish Dancer, all 2007 and made of pine or ebonized pine, are modernist constructions, as their additive use of geometrical forms makes clear. They have a certain affinity with Archipenko’s Cubist dancers, but are much more severely abstract, that is, purely formal inventions. But I think Gorbaty truly comes into his own in his low-relief carvings of the female body. The tension between the low relief, flattening the body, and the ripe abundance of female flesh, evident in the mass of the buttocks and breasts, as in Seaside Girls No. 2, 1990, makes the point clearly. One immediately thinks of Matisse and Lachaise, but their female nudes tend to be either more abstract or more realistic—“primitively†abstract (Matisse) or voluptuously realistic (Lachaise)—than Gorbaty’s female nudes, which are an uncanny mix of modernist flatness and Baroque abundance.

Gorbaty’s Reclining Nude No. 1, 1995 is readily comparable to Matisse’s Blue Nude, Memory of Biskra, 1907, but the buttocks of Gorbaty’s nude jut out into space more dramatically, and are more perfectly rounded, suggesting that the nude is more abstract than visceral, however viscerally seductive it may be. The contrast between one small circular breast, placed on her arm as though it was an independent globe, and the other large breast hanging from her torso and cradled in her other arm, makes clear how surreally abstract she is—all the more so because she is headless and her body is broken at the waist, with the upper part turned upside down so that it faces the lower part. Reclining Nude No. 3, 1995 is even more to the viscerally surreal abstract point, as her especially prominent buttocks, their flesh overflowing the ledge on which her body rests, makes clear. The fact that the full-bodied nudes are carved in wood—oxydized walnut—suggests that they are woodland nymphs. Wood also has its own erotic appeal—its own innate sensuality—which adds to the surreal seductiveness of her body, even as it confirms that it is completely natural and sensual, as nature at its most vital always is, and thus exciting to touch, if only with one’s eyes.

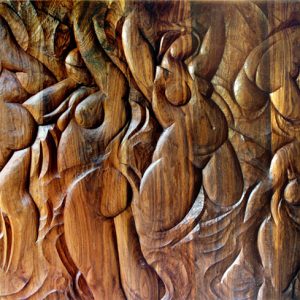

Like Gauguin, Gorbaty understands the “savage†power implicit in wood grain—as subtly rhythmic and emotionally evocative as moving water, and as charged with undercurrents–and the haptic power of carved wood. Gorbaty’s carving is gesturally charged, just as his toned wood, with its atmospherically dark and luminous areas, suggestively transforms his sculpture into a painting. He is clearly trying to collapse—and eloquently finesses–the difference between three-dimensional sculpture (the rounded body reads as sculpture) and two-dimensional painting without denying it. The tension between smooth and rough surface—the pleasurably refined and the painfully raw, in effect between the civilized and the instinctive—adds a patina of depth meaning to the wood, all the more so because Gorbaty’s carving sets the work in process, as it were, suggestive of unconscious process, and makes it more “cutting,†and thus suggestive of suffering and hurt, however reverential—a homage to the organic–the carving may be.

Carving brings out the innate plasticity of wood more than modeling, although Gorbaty ingeniously models as he carves, thus collapsing what Adrian Stokes regarded as fundamentally different modes of sculpting—another integrative finessing of the opposites to Gorbaty’s modernist credit. “Carving conception,†as Stokes calls it, “causes its object, the solid bit of space, to be more spatial still,†while a “plastic material†is “freely†modeled, suggesting that space is dynamic and flexible rather than inflexibly fixed “in place,†and allowing a more ‘imaginative communion†with its material than carving a hard material allows.(1) Wood is a solid bit of space, but by reason of its organic nature it is inherently plastic—certainly not as hard, rigid, and intractable, that is, resistant to touch and as hard to work as stone–suggesting that Gorbaty’s sculptures render the plasticity of space (by way of the plasticity of the body, indeed, the plasticity self-evident in the curves of the female body) without denying the uncanny solidity of wood.

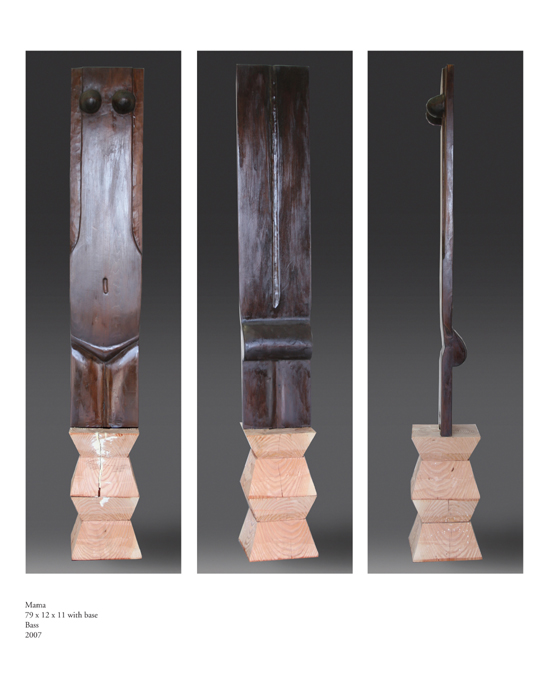

The bass wood Pregnant Woman and the cedar wood Female, both 2007 have a certain relationship to Brancusi’s totemic sculptures, as their pedestals indicate, but they are all wood, while Brancusi’s pedestals are typically of stone, and his figures usually bronzed: Gorbaty is unremittingly organic in comparison, in line with his idea of woman as the embodiment of vital Creation, to refer to a 2007 sculpture of fir wood. The fantastic Creation of Eve, 1977 and Eden, 1980, both carved in pine wood, makes the point clearly. We are in paradise, and Eve is its perfect flower, her body, with its core dynamics—its stalk-like torso, bulging thighs, and delicate head—suggests. Gorbaty brings out the inherent abstractness of her body without de-naturing it, as Brancusi does. Gorbaty implies that nature has as much rights as art, which can never completely dominate her. Art must work in tandem with nature to strike an esthetic balance between them. Nature should not be bent to the will of art, and finally erased from it, which is what occurs in modernist formalism, that is, abstraction for the sake of abstraction, purity for the sake of purity—rather than to articulate the dynamic essence of nature. Gorbaty clearly repudiates “absolute art†however much he uses abstraction to make the rhythms of nature—particularly as embodied by the twists and turns of the female body–esthetically evident.

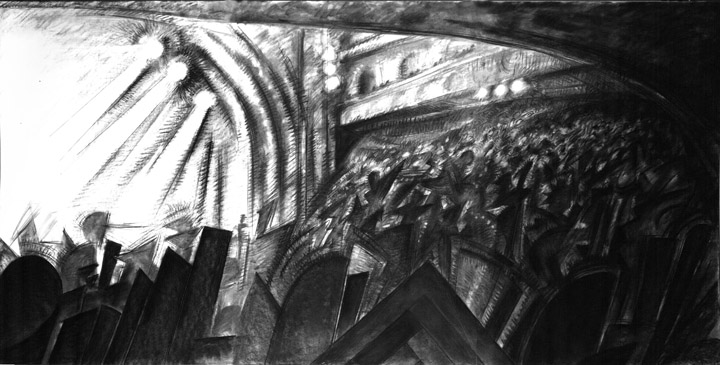

But not only, as the wildly expressionistic snake in Gorbaty’s extraordinary version of The Temptation, 1981, the futuristically dynamic Dog Looking Up and Wolf, both 1994, the Cubistically fragmented Creation of Adam, 1975 show. These and other works show that Gorbaty uses modernist ideas and methods to breathe fresh life and find new meaning in age-old myths and archetypes. Even death acquires existential import in Gorbaty’s 4856 (In memoriam), 1992, the most convincing memorial to what in effect amounts to a holocaust—the “more than 14,000 Jews…killed by peasants and crusaders on their way to Jerusalem in the first crusade,†as Gorbaty writes—I know. Like all of Gorbaty’s low reliefs, it integrates the naked figure, now heroic, and “convulsive†modernist forms. A Jewish theme also appears in Peniel, 1989, but the dynamics of the wrestling figures—Jacob and the angel, “face to face†(the meaning of “penielâ€)—seems more to the point of the relief than its theme. Dynamics are on visionary display in Gorbaty’s Jazz, 2002, a tour de force of unleashed energy, integrating expressionist and Cubo-futurist ideas of movement.

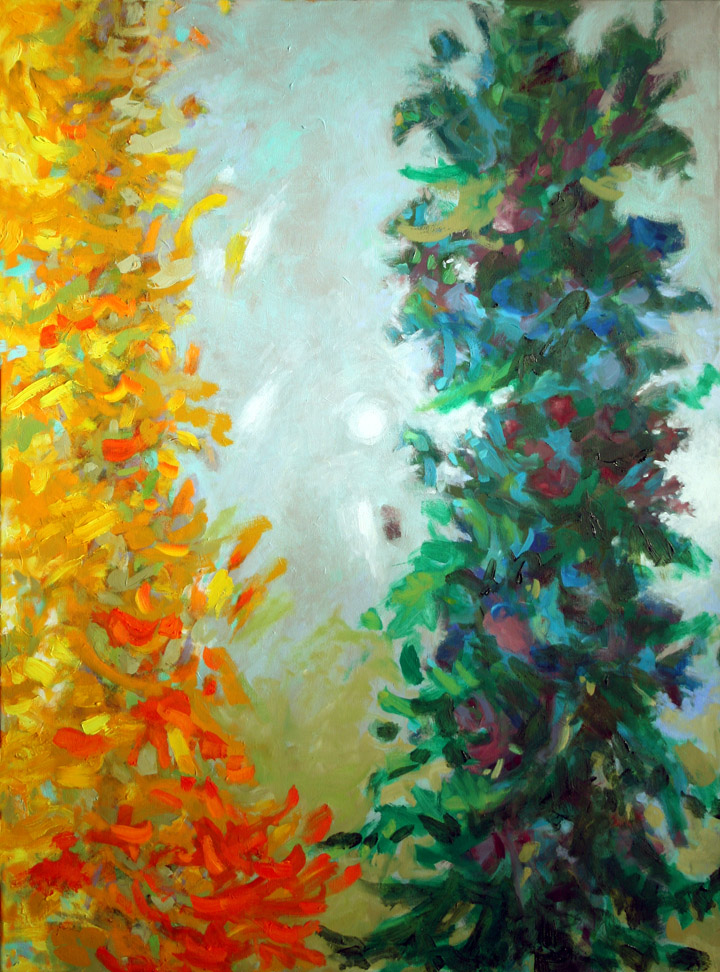

Gorbaty is a visionary working in an abstract mode—integrating the variety of esthetic innovations that inform abstraction—with no sacrifice of the vitality that only nature can confer. His love of nature is evident in his paintings and pastels—brilliantly colored landscapes—and his use of wood, an organic material emblematic of natural process. His feeling for nature enables him to embrace its dynamic forms without being overwhelmed by them, much the way Jacob wrestled with the angel without being overcome by him. Instead, Jacob was blessed by the angel, just as Gorbaty is artistically blessed.

Notes

(1)Adrian Stokes, “Stones of Rimini,†The Critical Writings of Adrian Stokes (London: Thames and Hudson, 1978), I, 235