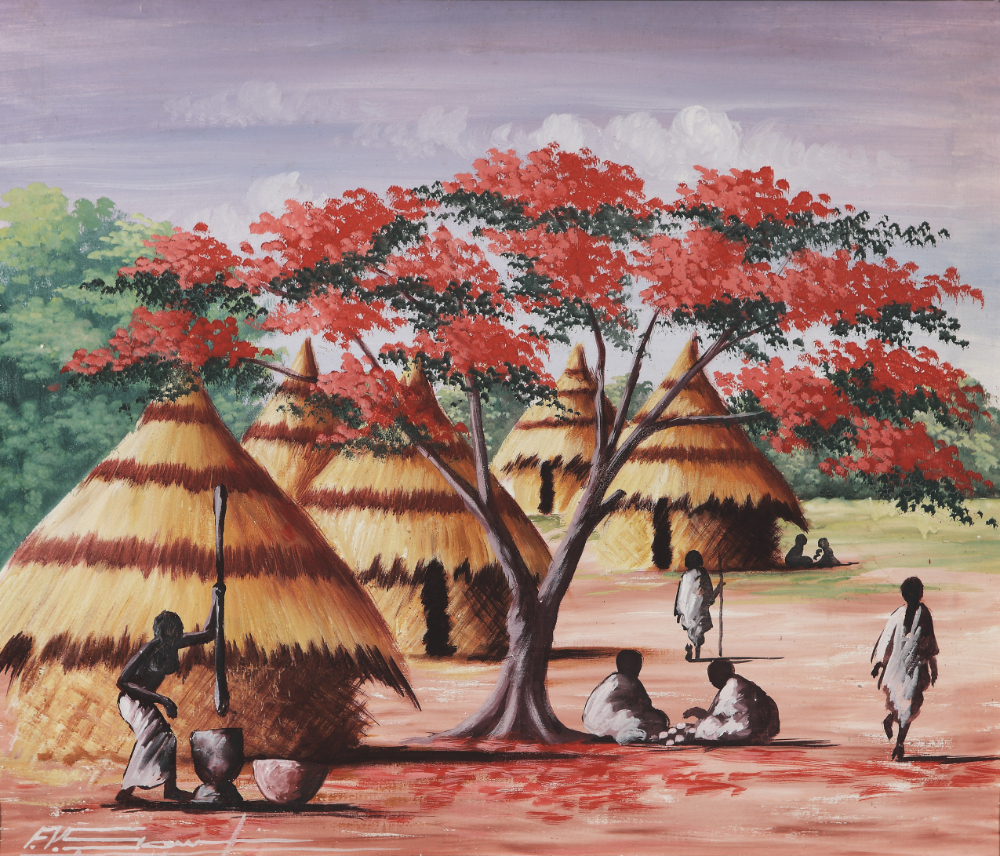

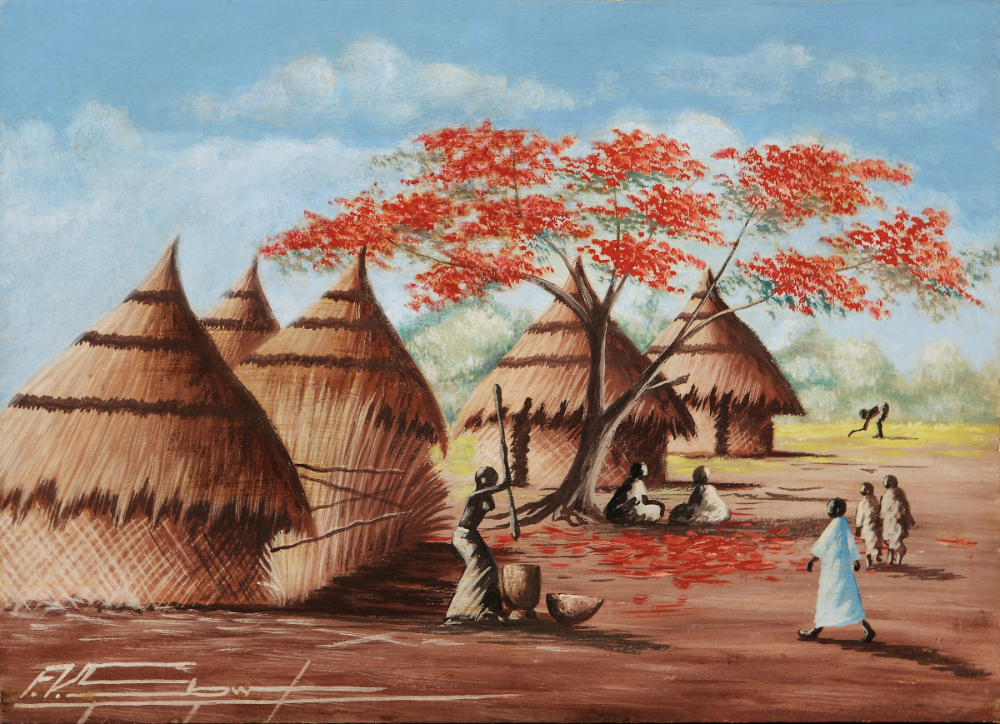

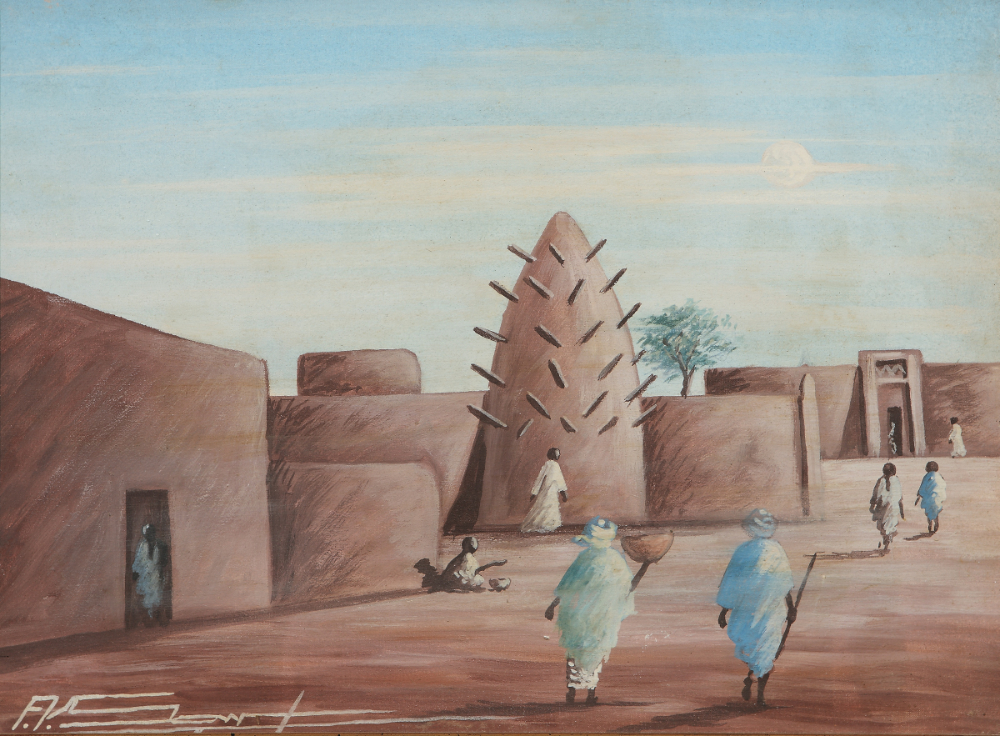

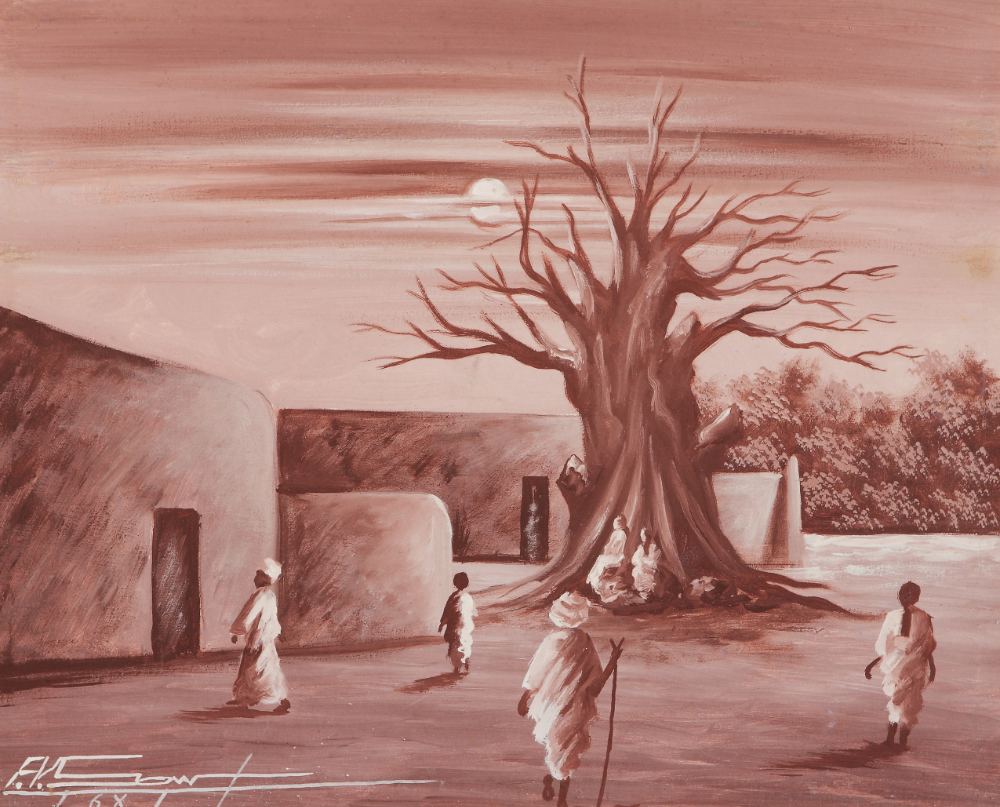

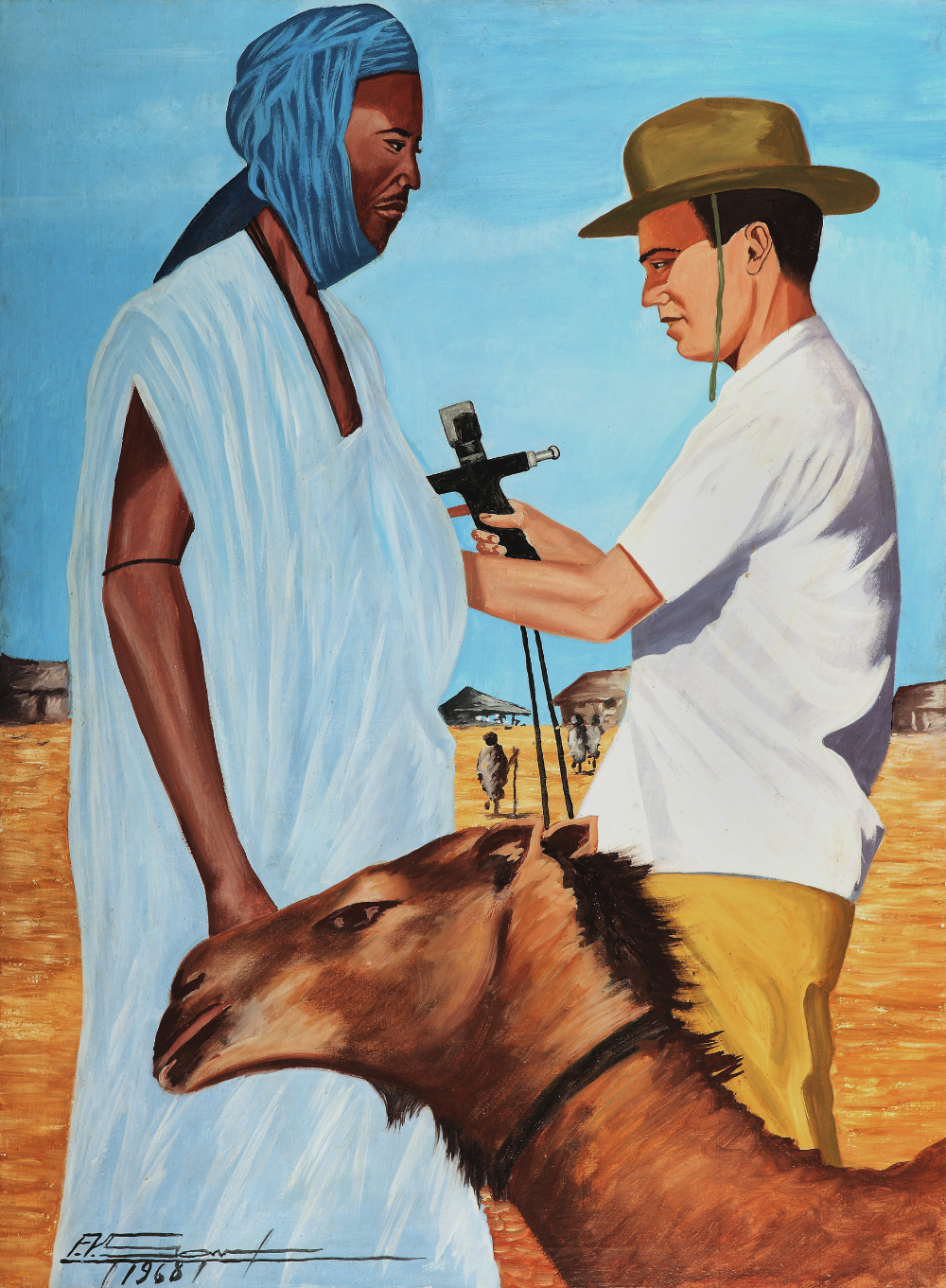

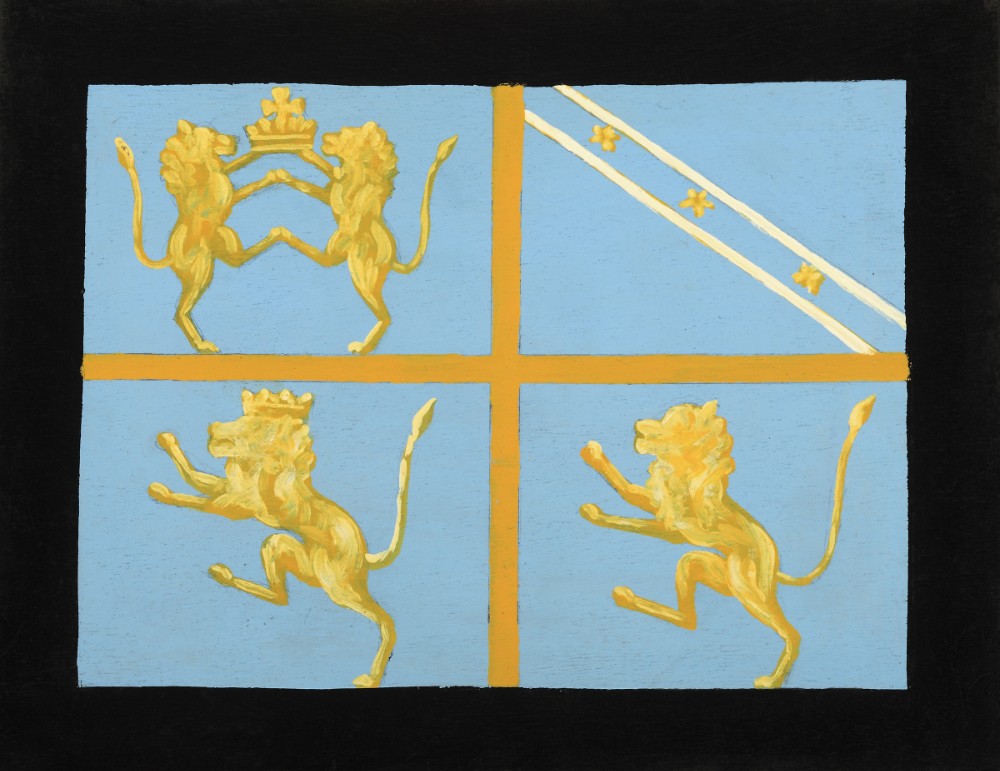

Victor Forestier Sow was a pioneer painter in the West African Republic of Mali. The son of a Malian mother and a French father, he first studied painting in Mali (then the French Soudan) and later in Paris. His most active years were in the 1960s and 1970s which were an exciting cultural, social, and political time in Mali. For it was in those decades that Mali achieved independence and began to forge a national identity.

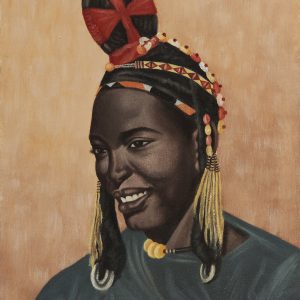

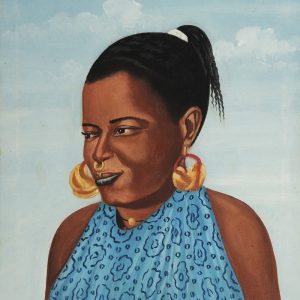

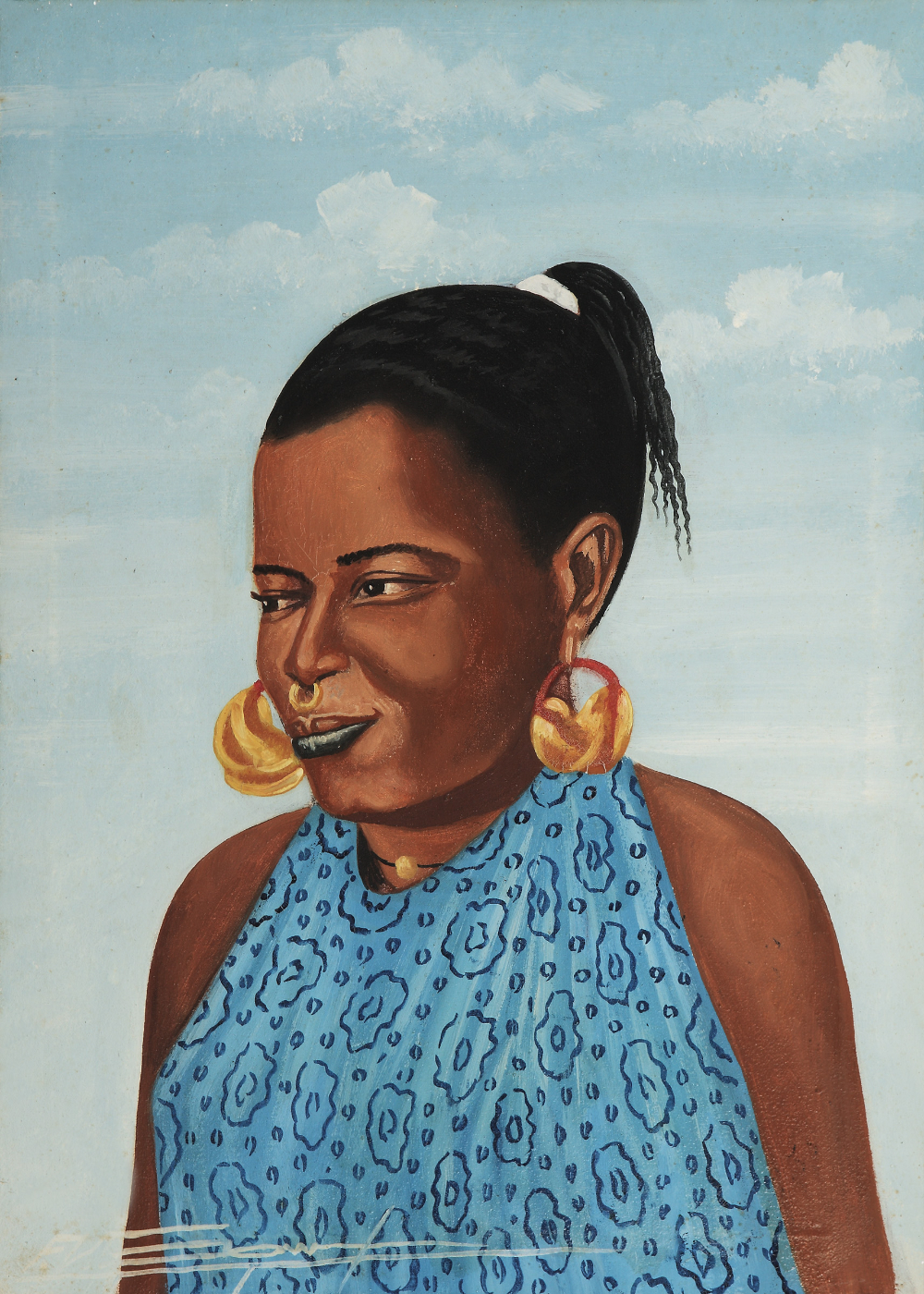

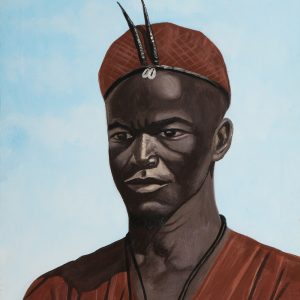

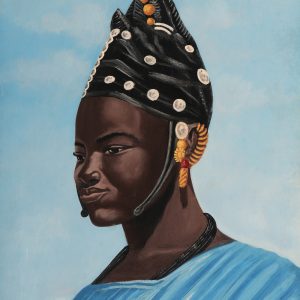

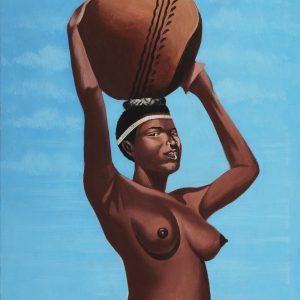

Sow’s artistic participation in Mali’s efforts to unify a culturally and racially diverse population into a single-voice polity is reflected in his choice of subjects. His focus was primarily on the diversity of Mali’s landscapes and its peoples, and on both ancient and modern architectural structures. In choosing these subjects, Sow was using his brush as a means of participating in Mali’s nation-building and socialist discourses. His paintings reveal that he was ever conscious that he was an integral part of a rapidly changing society.

Sow sometimes found iconographic inspiration for his paintings in photographs, illustrations, and postcards. This represented mimetic painting since he remained faithful to the original images and their nuanced colors. On the other hand, he frequently created finely detailed canvases reflecting his sensitive awareness of Malian village life. Stylistically, a number of his paintings can be considered folk art.

Sow also produced portraits for both local and foreign clientele. A number of artists in West Africa at that time engaged in this type of painting. In so doing, they sometimes created larger and more durable color representations of photographs that were either faded or damaged.

Sow’s paintings have great socio-historical significance because of when they were created. However, they are also unique because so many of them have survived. Mali’s climate is not kind to canvases. A long, hot, and dusty dry season and a shorter, stormy, and humid rainy one are inimical to the survival of paintings unless properly stored and conserved. Not surprisingly, the paintings of a number of Sow’s Malian contemporaries did not survive into the twenty-first century.

This catalog and the exhibition it accompanies present seventeen of Victor Forestier Sow’s paintings. Completed more than four decades ago, they are in excellent condition due to careful conservation. They were collected in Mali by Pascal James Imperato during the six years he lived and worked in the country. Some were commissioned by Dr. Imperato while others were presented to him for sale by the artist. They probably represent the largest collection still in existence of the paintings of any pioneer Malian artist. For this reason alone, they occupy a unique position in the history of Malian painting.

The text of this catalog consists of essays by three contributors, Austin C. Imperato, who studied art in Europe, and who grew up with this collection from early childhood, offers analytical insights into these paintings. Pascal James Imperato personally knew Victor Forestier Sow very well and shares his personal remembrances of him and his art. Paul Ramey Davis, who recently completed extensive field studies of contemporary painting in Bamako, Mali, clearly describes the art world of which Sow was a part.

Victor Forestier Sow’s paintings open our aesthetic senses to the pioneer era of a Malian artistic tradition. The beauty, power, and energy present in these paintings also provide us with an intimate understanding of the Mali of that time, and of an artist who successfully bridged two separate cultural traditions.

The Queensborough Community College Art Gallery is pleased to present this very exciting exhibition. We wish to thank Paul Ramey Davis, Austin C. Imperato, and Pascal James Imperato for enriching this exhibition with their excellent contributions to the catalog.