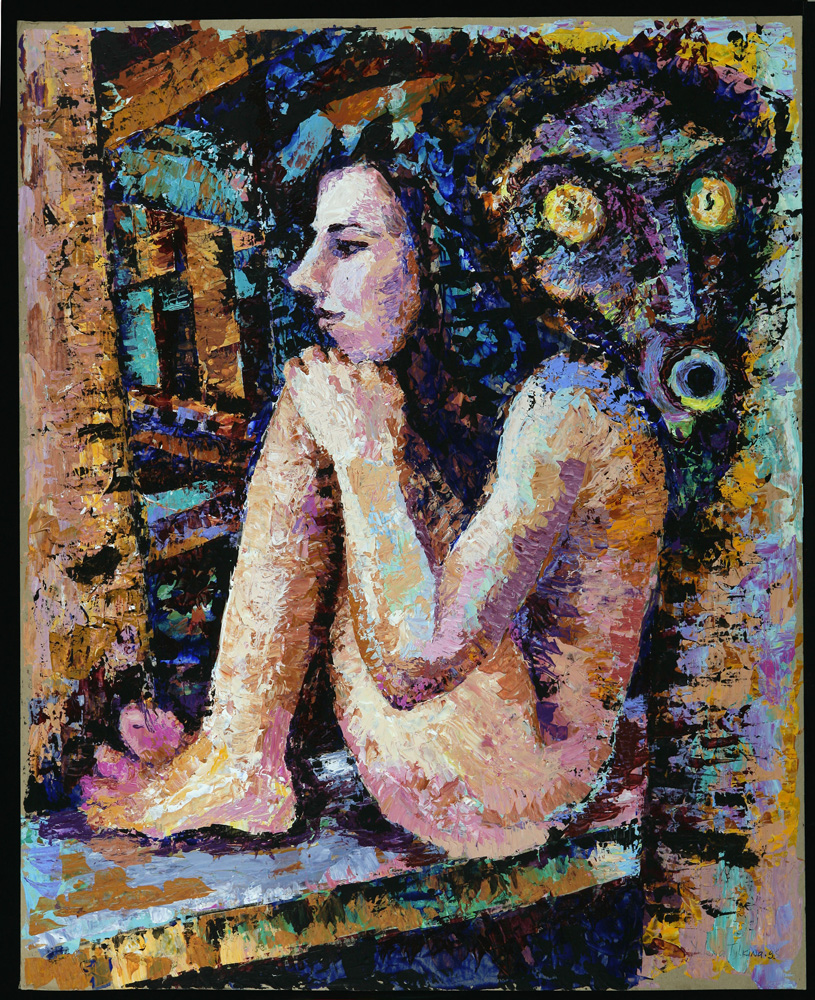

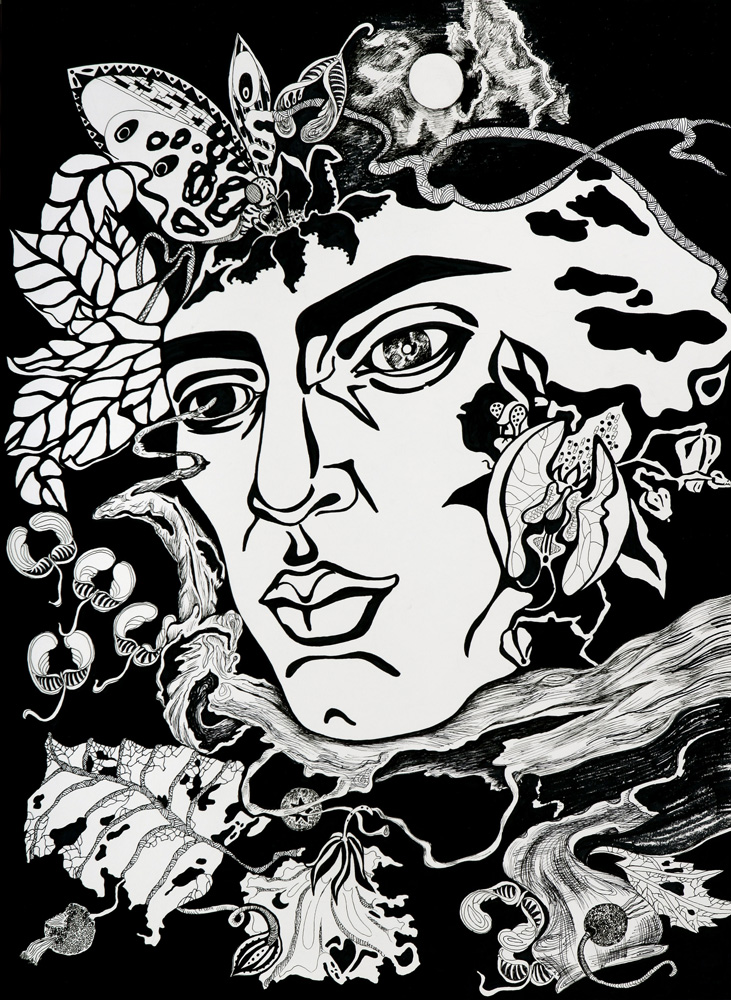

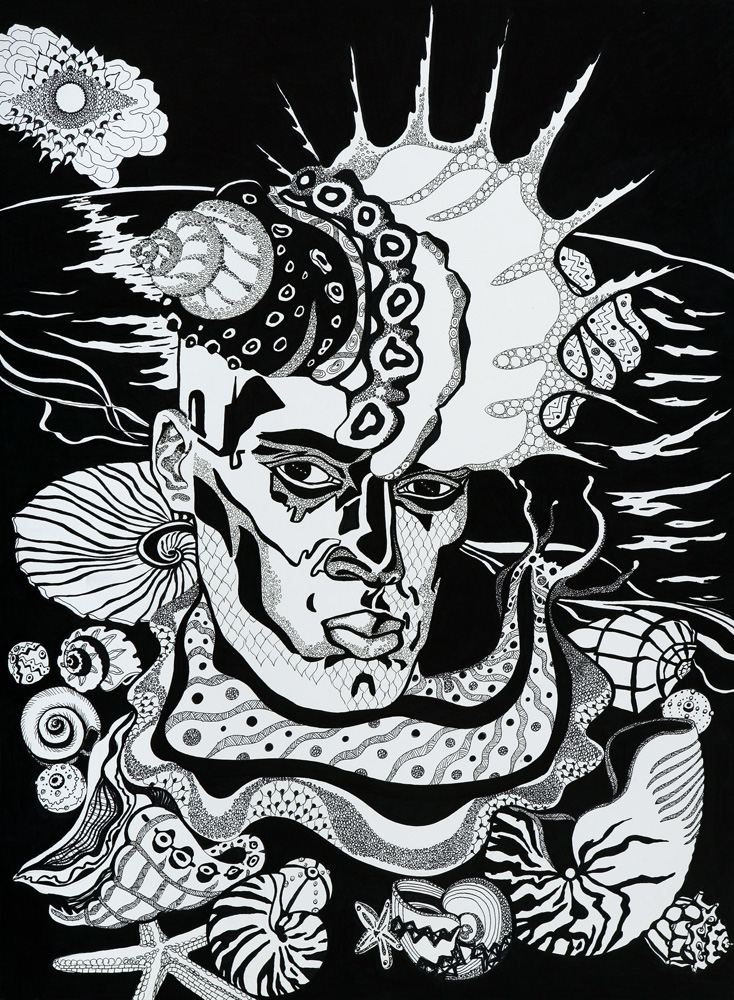

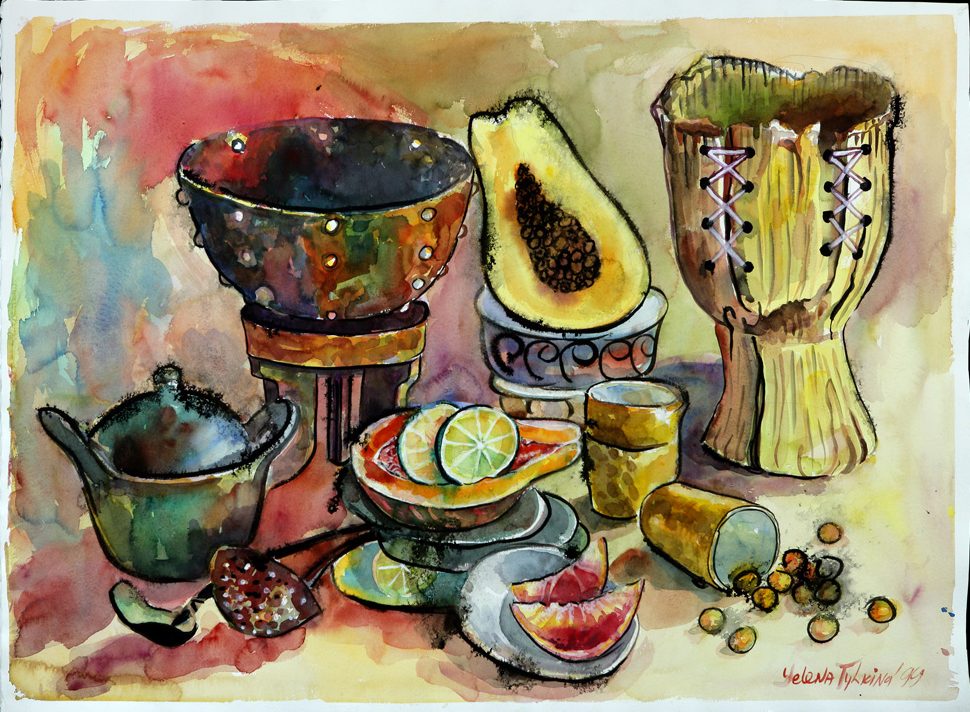

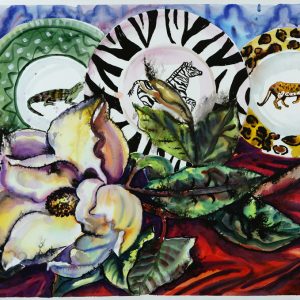

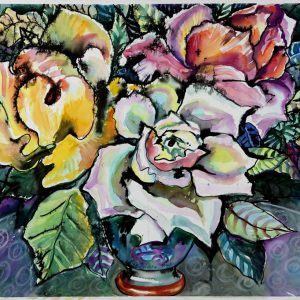

I have to say that I was taken with Yelena Tylkina’s images of flowers, all lushly blossoming and often passionately red—luridly alive still lives—and taken aback (at least momentarily) by many of her female figures, not because of their nakedness, but because of their raw narcissism, all the more confrontational because of the raw graffitied (Bronx) environment in which they appear. Dramatizing the female body—presented with photographic clarity, and hauntingly nuanced by atmospheric paint—in what are clearly dream pictures, as the fantastic images (many from primitive art) fixed on their flat space indicates, Tylkina conveys both the angry glory and tortured unhappiness of being female.

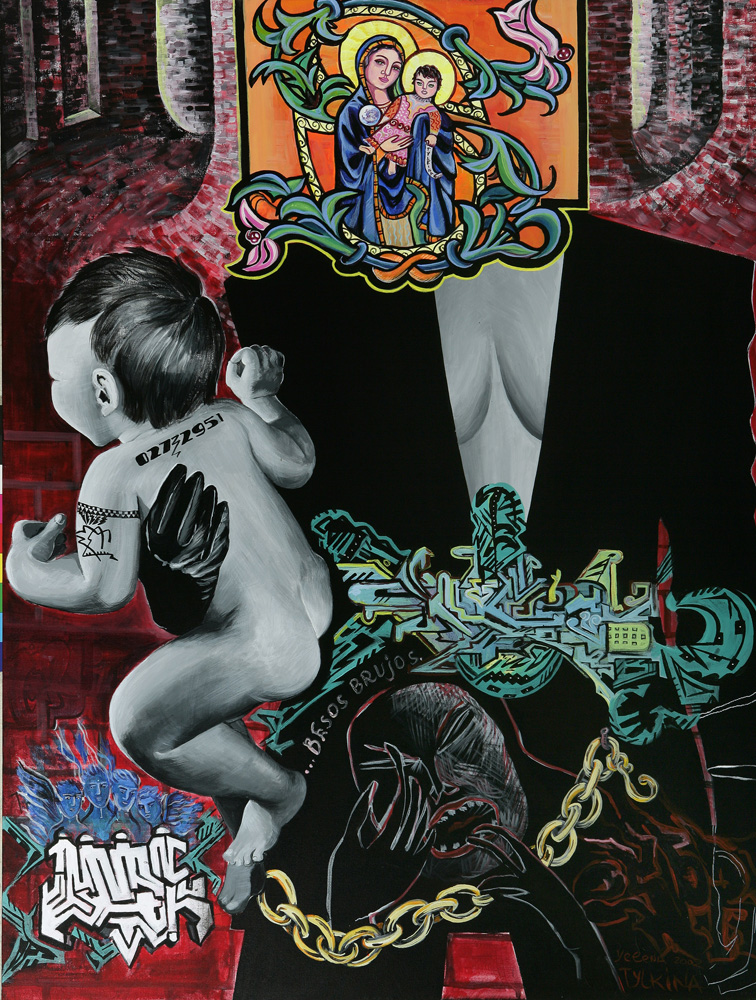

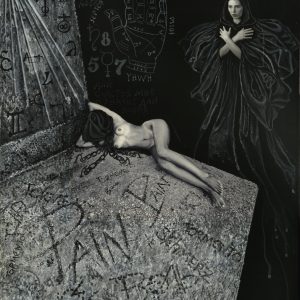

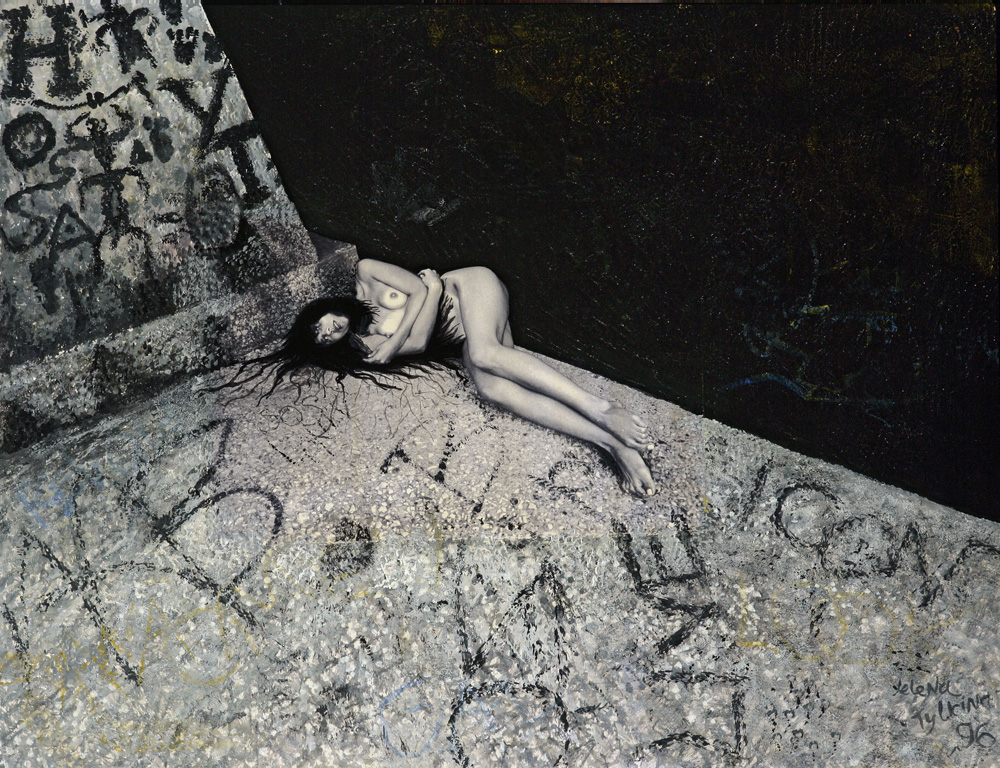

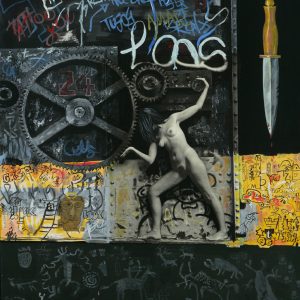

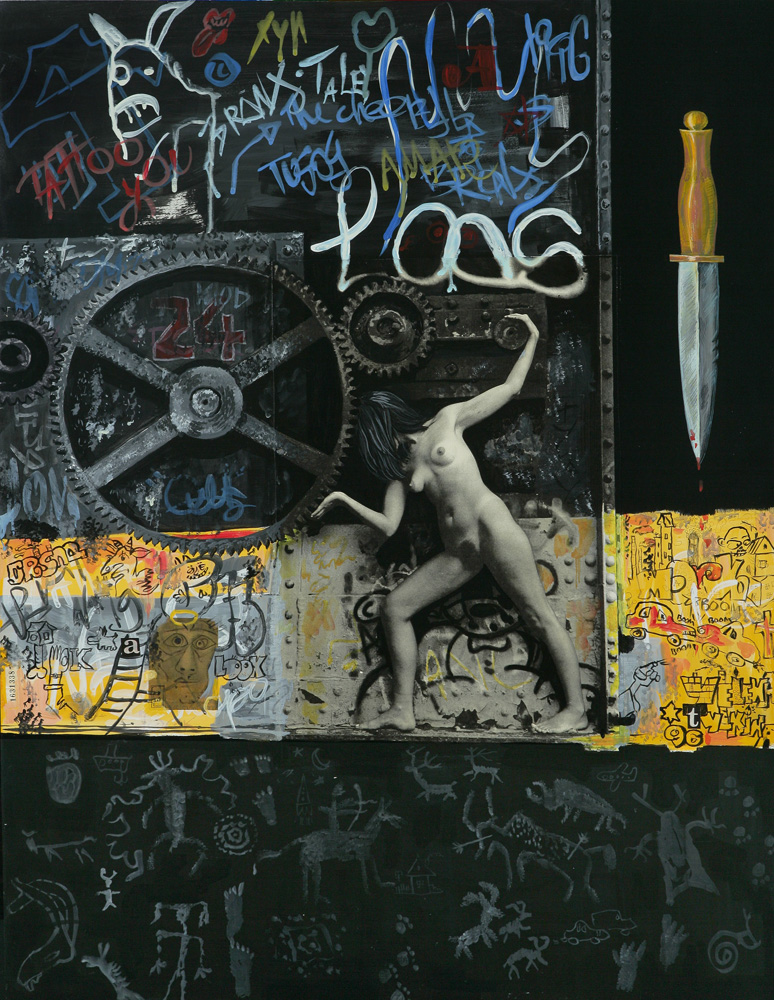

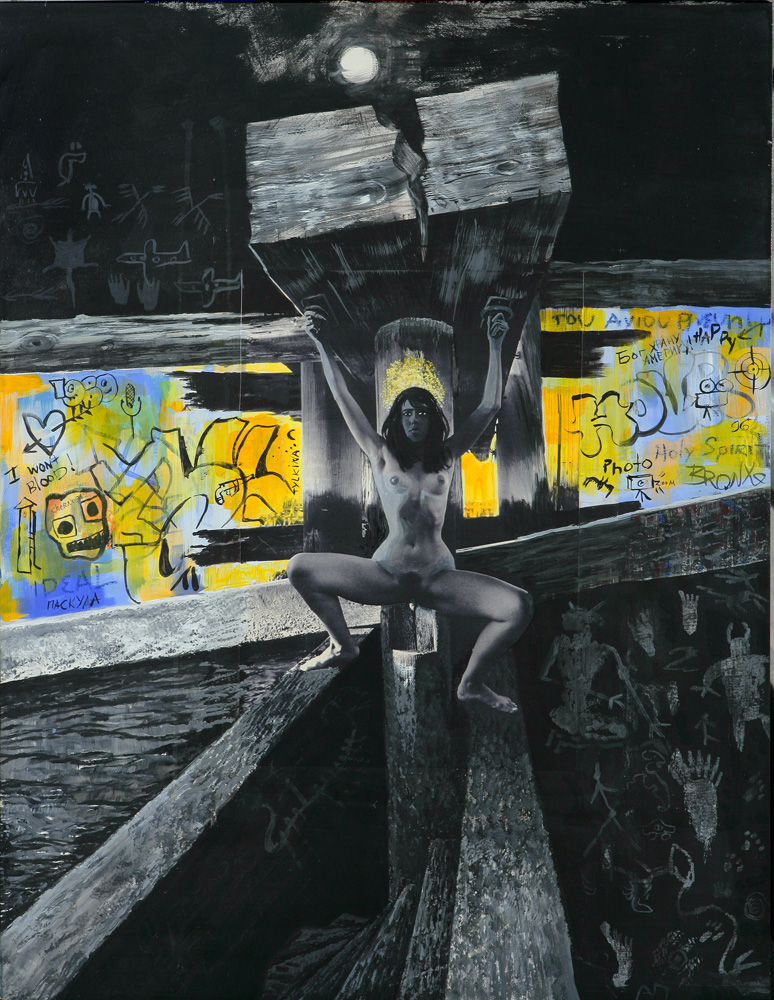

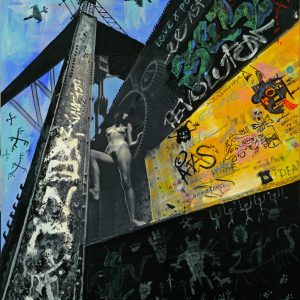

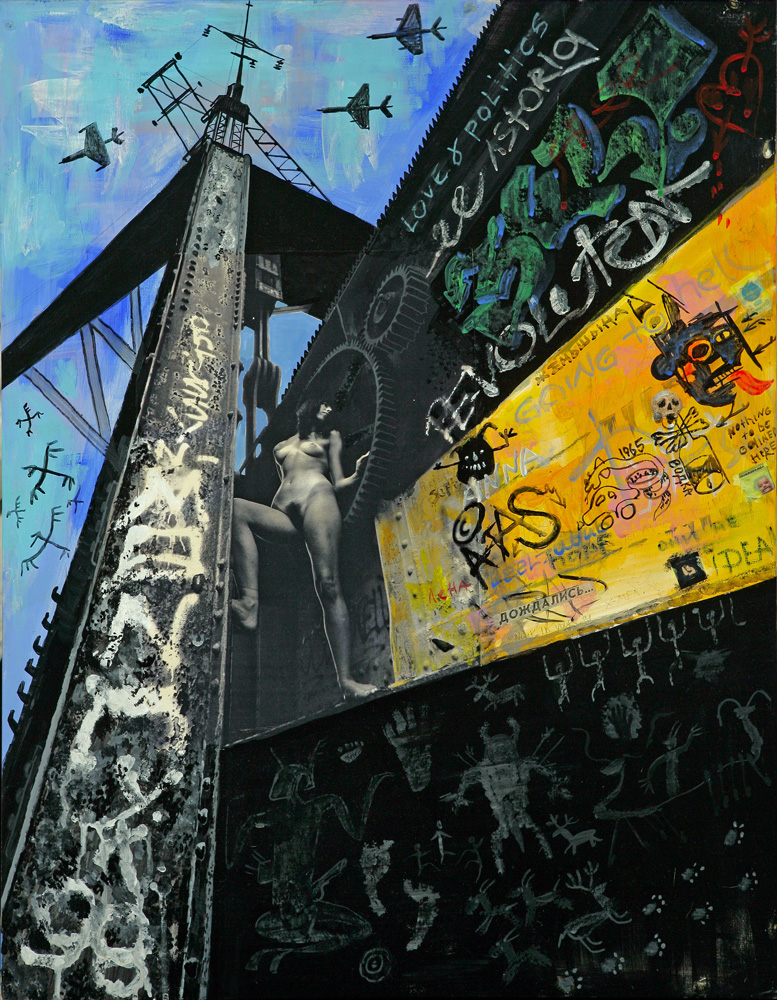

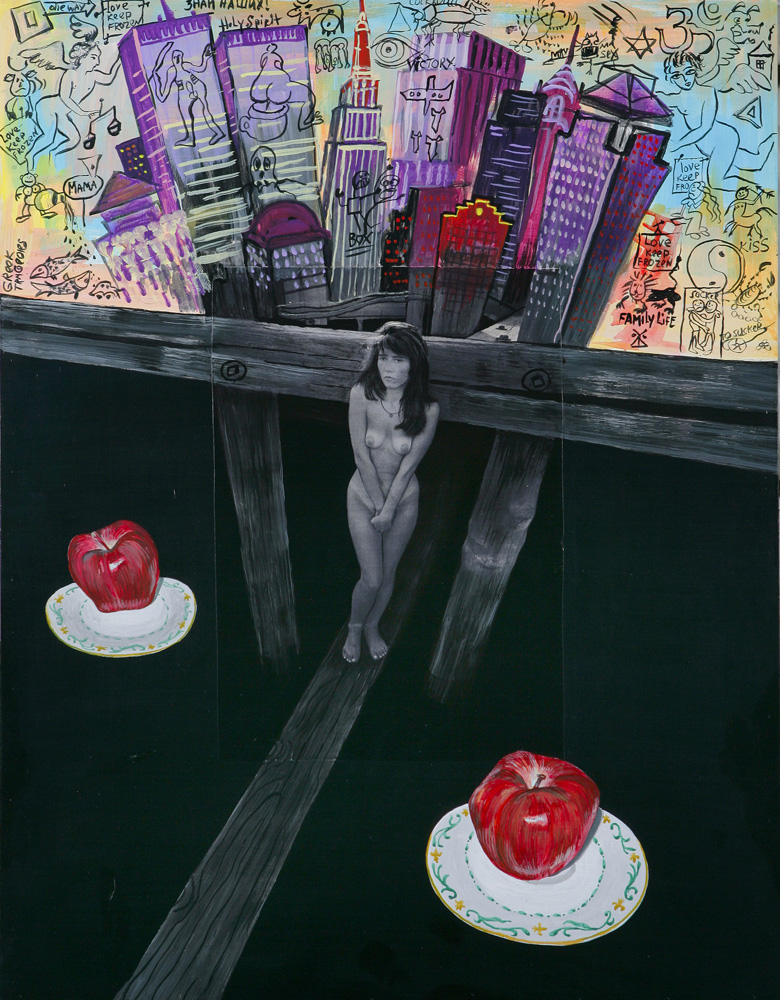

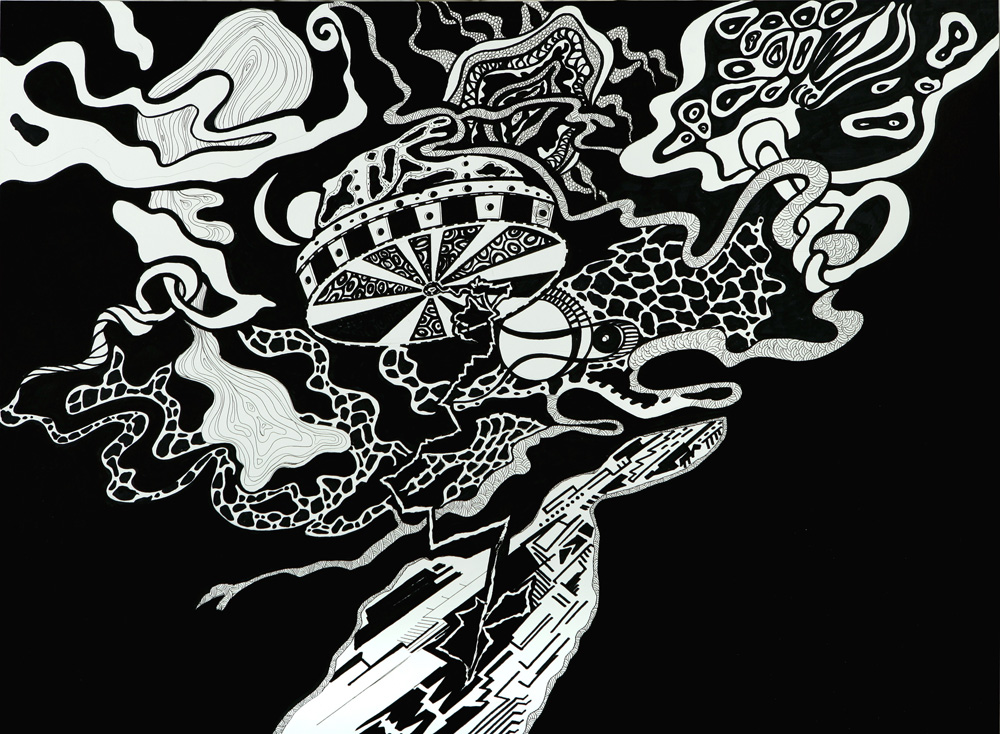

The point is made clearly in three gloomy works—their darkness may be alleviated by patches of bright color, but it never lifts. In one a naked, youthful, well-built woman holds up the wheel of the world, like an Atlas, keeping its machinery moving despite the surrounding chaos. But she seems to do so at the cost of her identity and individuality, as the hair that shrouds her face—the proverbial place where the inner self becomes manifest—suggests. In the second work this same female, her face now visible and her wide-open eyes staring at us, confronts us with her nakedness, all the more intimidating because her genitals are exposed. She squats in the ruins of some huge structure, holding up a fragment of its heavy roof—a sort of female Samson at the ironical moment she brings down the temple, physically blind and bound but in full consciousness of her destructive and self-destructive act and humiliating situation. She is self-possessed even as she is doomed, as the abyss below her implies.

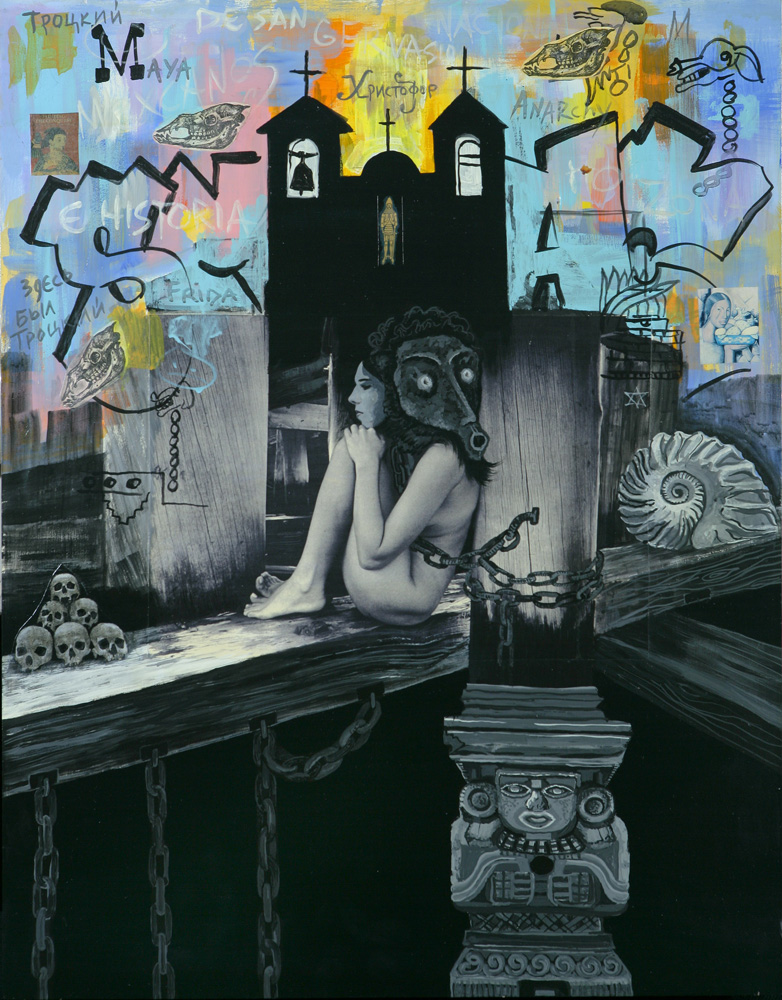

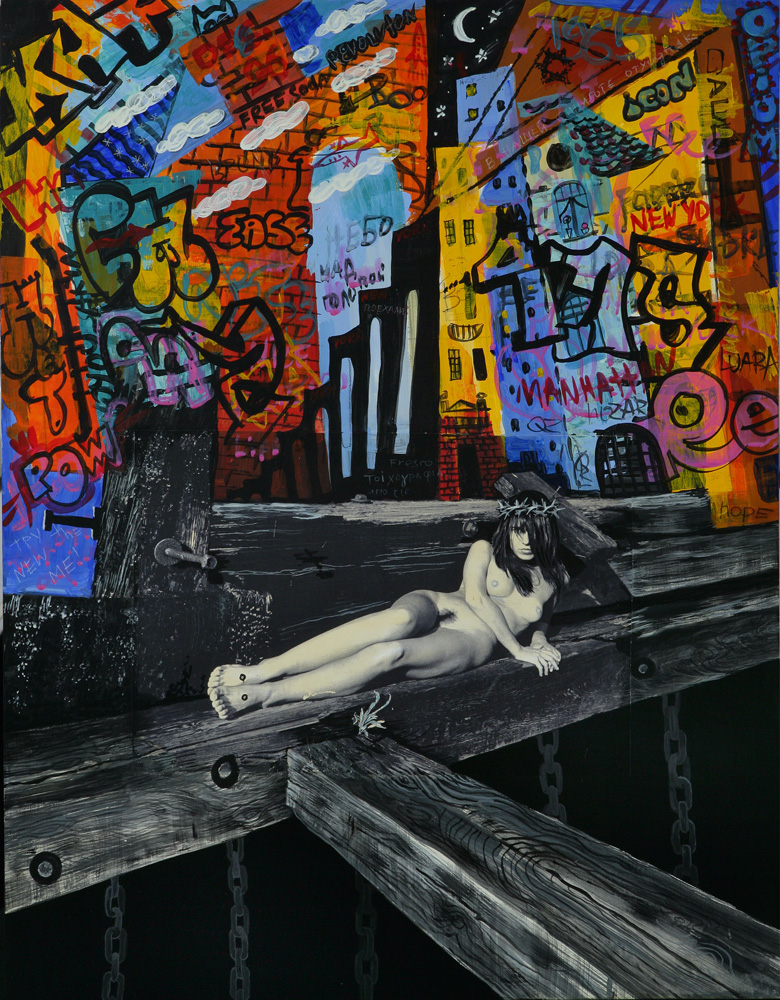

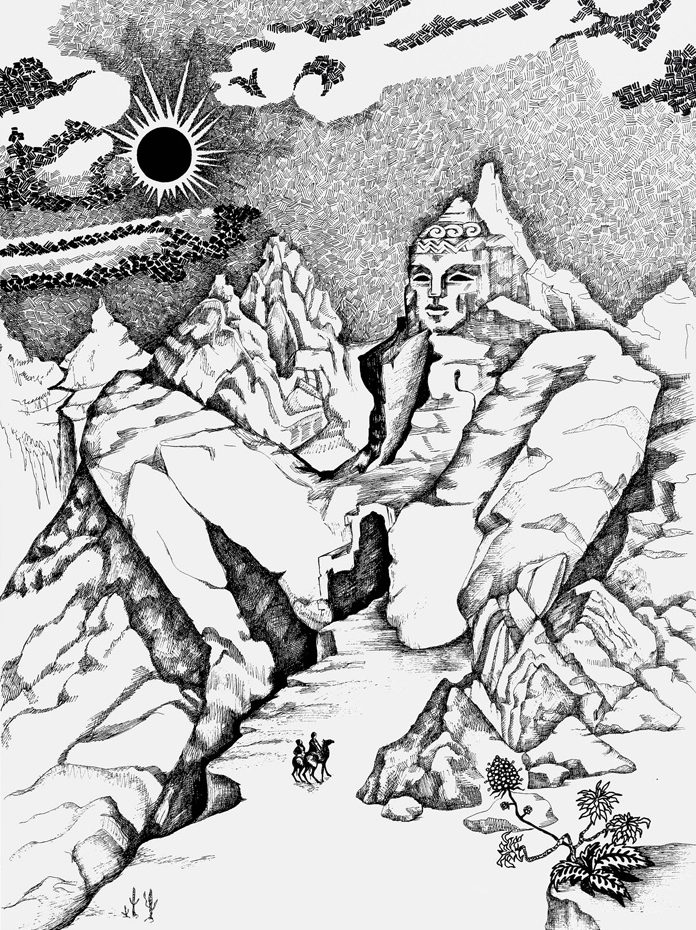

Finally, we see this same haunted naked female, now with an African mask attached to the back of her head, and thus implicitly two faced—and suggesting her inner torment–chained to a decaying wooden column crowning an Aztec sculpture and sitting on a huge beam (like that in the second picture) spanning a black void. Chains hang from the beam. There’s a pile of skulls to her left and another wooden column—a totemic fragment–now marked with a small Jewish star. Symbols of death and suffering abound; even the flat church façade that frames her figure is pitch black, however luminous the openings in the towers. This woman seems to have lost her strength and will power. If the African mask is any clue, she is imprisoned by her own dark passions. Her existence is precarious, as her position above the void indicates.

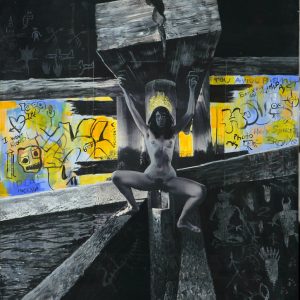

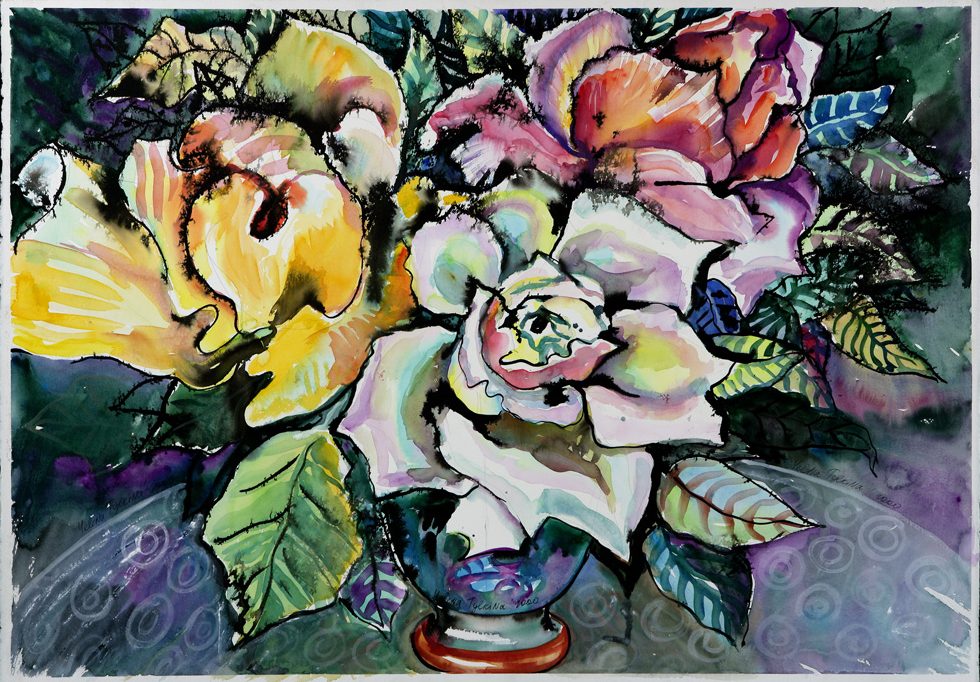

There is an air of violence and despair in all three pictures. The antidote to their poisonous mood is the erotically charged, ecstatically colorful, manically intense flowers in Tylkina’s still lives. She oscillates between the extremes, finding no place to rest. Not even the crosses that often appear in her pictures offer reassurance. In one a young woman’s beautiful face appears in the center of an enormous black cross—an enlarged quotation from Malevich, who came from Vitebsk Province, where Tylkina was also born (the abstract Suprematist character of the cross is made evident by the various small traditional crosses that surround it)—implying that she has been crucified. Still alive, she unflinchingly meets our gaze, but her body has disappeared into the mortifying black. (The work also suggests a struggle between modernist abstraction and traditionalist representation—however leavened by primitivism and surrealism—for the soul of her art.)

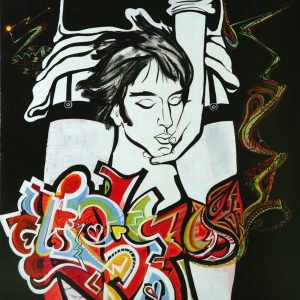

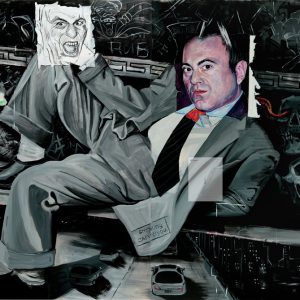

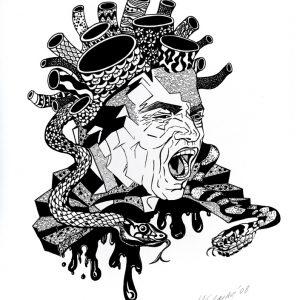

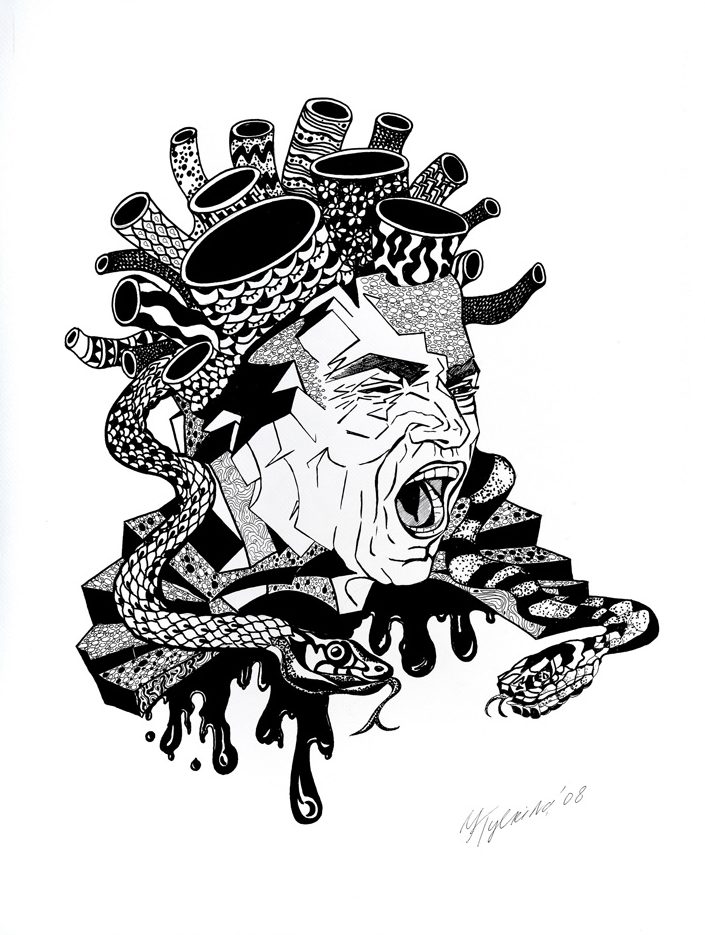

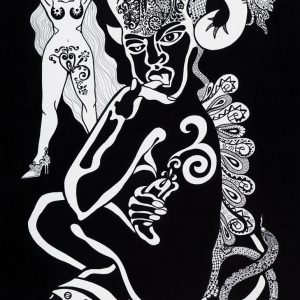

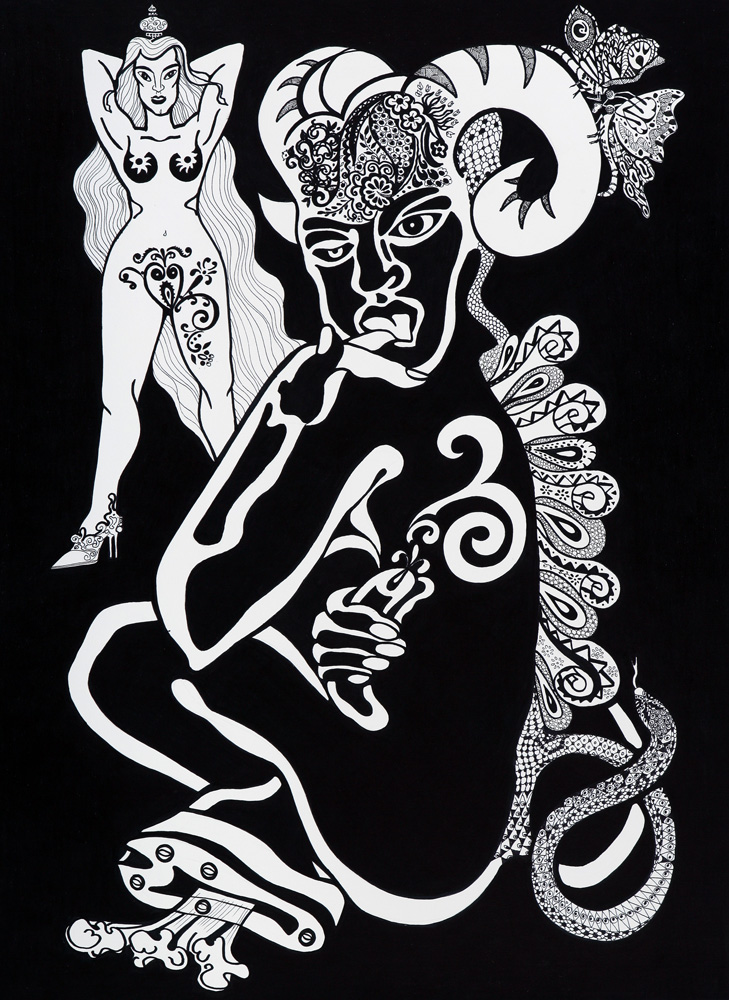

I am suggesting that Tylkina’s works are by and large allegories of female identity. There is a sort of surreal portrait of a male figure, Anastasios Sarikas, but it seems beside the larger point of her oeuvre, although his strong personality suggests the dominance of the male over the female, symbolized by the comparatively small flower, again in full blossom, at his feet. He turns away from the flower, as though indifferent to its wonderful presence, to confront the spectator with his glance, perhaps hoping to dominate her as he dominates the flower, a precious thing of rare and natural beauty. He is clearly a conquering male, awkwardly at rest but still vigorously, perhaps arrogantly, alert. Just as the female fights to hold her own in her grim environment—gain control of it, however finally overwhelmed and ignored by it—in the works previously mentioned, so the flower is dismissed by the male figure.

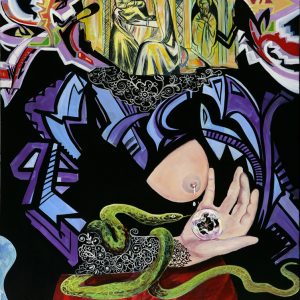

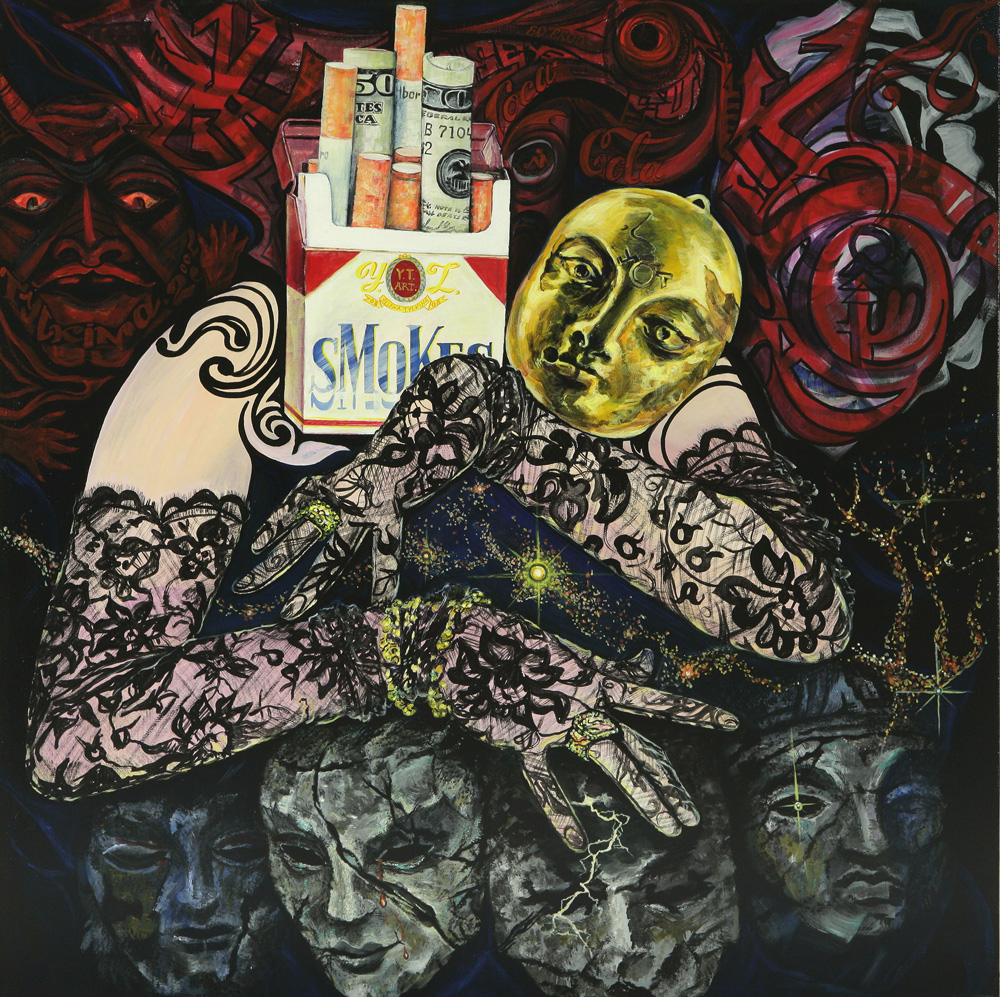

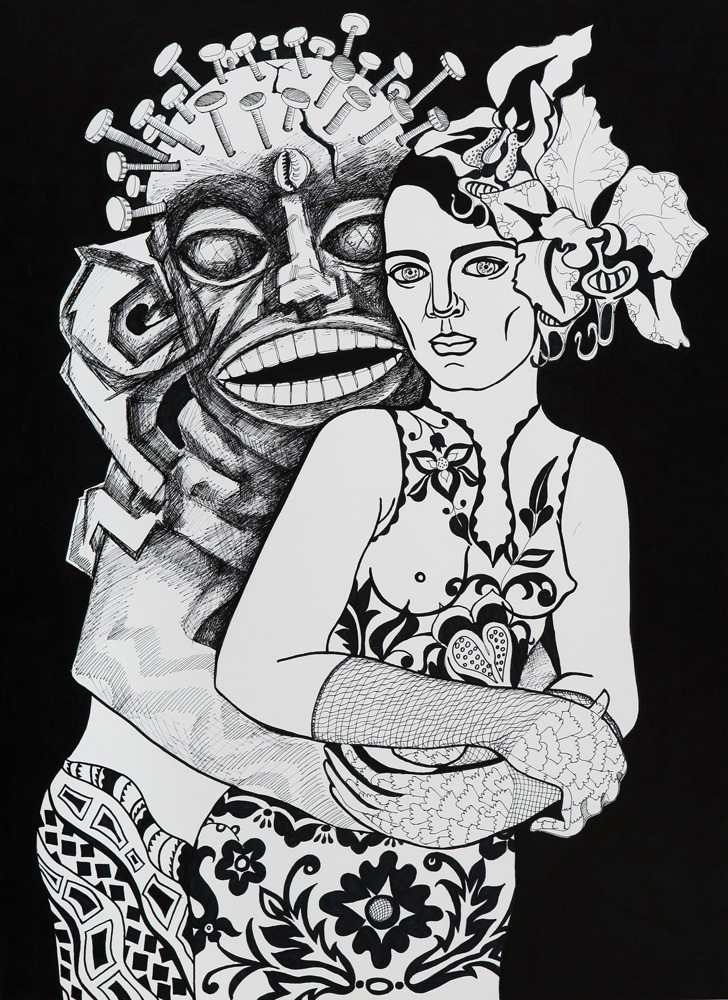

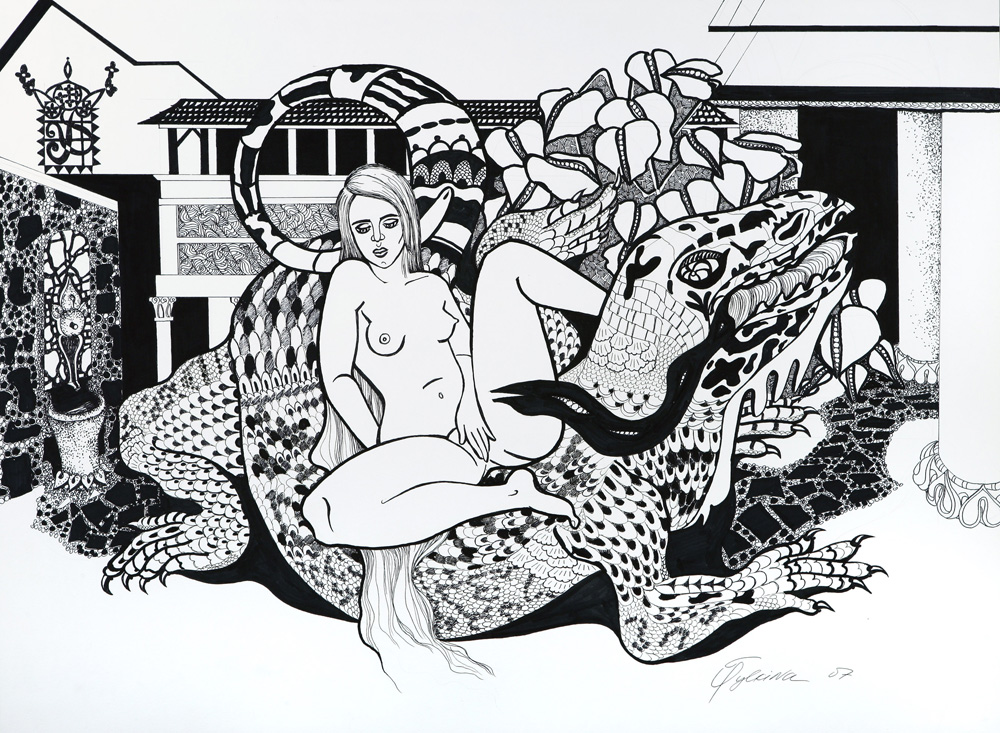

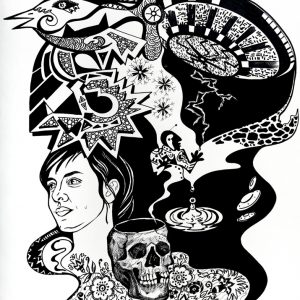

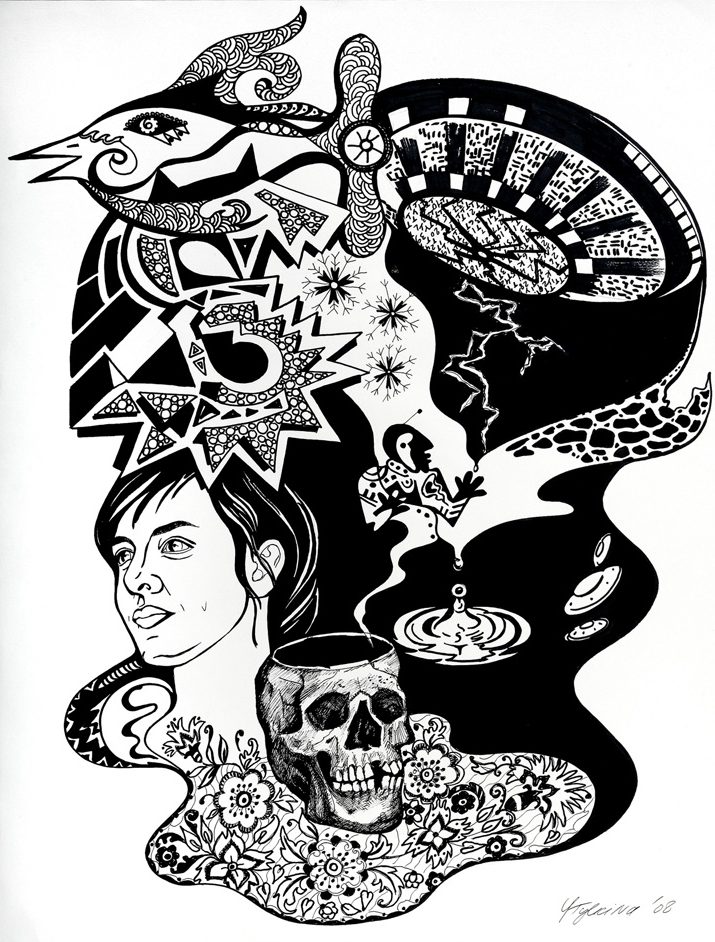

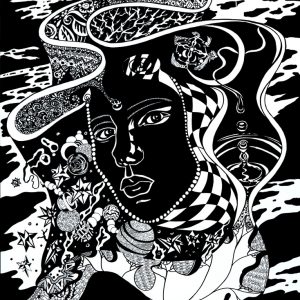

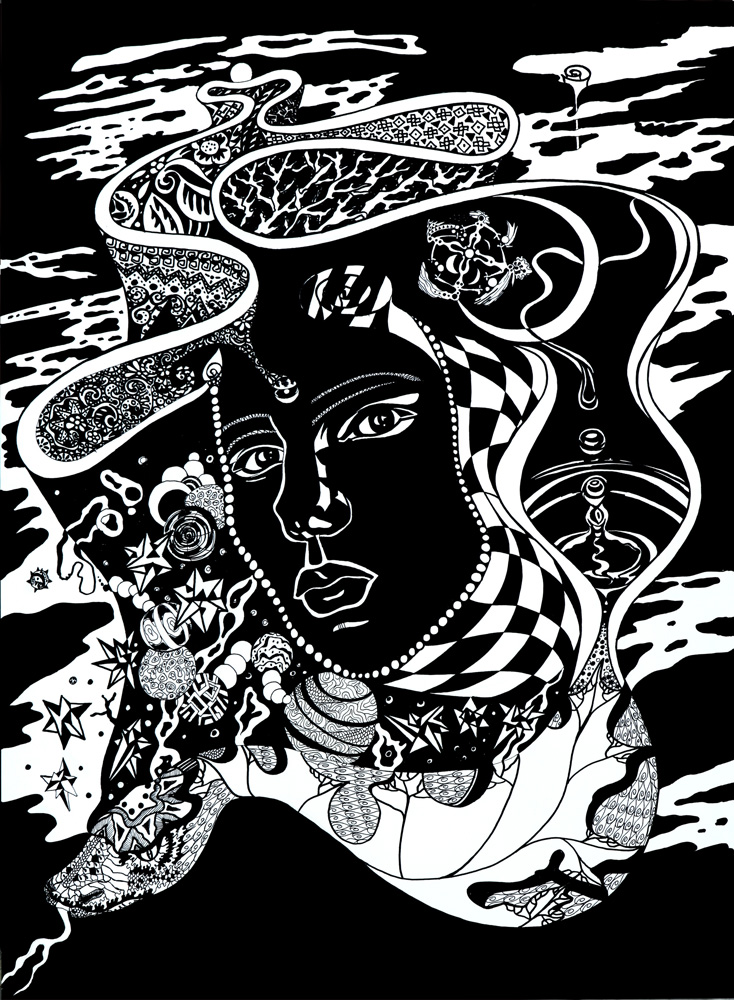

Going further, and looking at Tylkina’s oeuvre as a whole, I suggest that her works are an intriguing mix of self-hatred and self-love. She loves the seductive female body, and symbolizes its desire in many works, but she shows its frustration and dubious power in other works, suggesting a certain self-hatred. Narcissistic female desire is as natural and spontaneous as the floral pattern on the dress and the flowery head-dress the woman wears in one black and white work. The beautiful woman welcomes the embrace of a primitive male figure wearing an African mask marked by nails—a sort of god of the emotional underworld. Here the female figure is comfortable with her body and desire. She is as instinctively alive as the primitive male figure, although its monstrousness may symbolize the destructive character of her powerful sexuality, should she lose control of it. Is that the secret of the grim works I have already discussed: is the struggle to take control of the dangerous and collapsing society around her a symbol of her struggle to take control of her dangerous instincts and collapsing inner world?

Donald Kuspit