Autobiography

Girl Meets Boy

She’s invited up to his apartment for the first time. As he politely holds the door open for her, he gives the usual disclaimer, “It’s not usually such a mess.” She starts to wander around when she notices that she’s being followed. “It’s really disgusting,” he says, shutting the bedroom and study doors and guiding her back into the front room, “I’d prefer if you didn’t look around.” Limits are set; barriers are established. She can go into the front room, but not into the side rooms. The kitchen is okay, as long as she doesn’t look at the sink. She can use the bathroom, but she can’t open the medicine cabinet.

He points for her to sit down in a chair, and then he begins an elaborate game of show and tell. He brings her some books, then some family photos to see. He hands her the strange salt-and-pepper shakers he found while thrifting, and he shows her postcards from his trip to Europe. He brings her more beer, then he brings her more books.

While he’s showing her his books, what she’s really noticing are all of the empty beer bottles, the pile of pizza boxes, and the job application letter, lying, half-finished, on the floor. What she’s doing is wondering about what’s hidden in the bedroom, and what’s lurking in the study. What she’s trying to do is read between the lines, discover the stinky, muddy layer of stuff that lies beneath and behind what he considers to be clean, interesting, and presentable.

Stuff/Photographs

But is it actually possible to uncover the truth about someone just by looking at the stuff they surround themselves with? Stuff acts as a mask or a buffer: an index of how we want to be seen or how we wish to protect ourselves. Rarely does our “stuff” act as an index to our unmediated “self.” What we discard is often more telling than what we choose to keep. Nevertheless, our stuff forms our exoskeleton: an accumulation that serves to define and defend us.

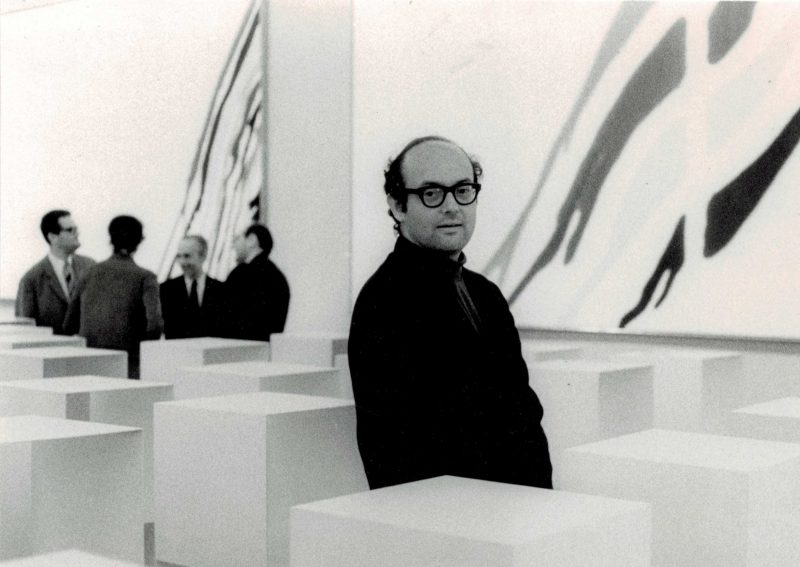

Within the mass of stuff we surround ourselves with, photographs, in particular, exert a powerful force as sentimental objects and also as (seemingly) objective records of our existence in the world. A photograph is taken as a truth, as real proof that something existed or that something happened. In his “Autobiography,” Sol LeWitt (1928 – 2007) exploits both the idea of photographs as objective records and the idea of stuff as objective proof. Photographs and stuff act as a record and an assurance of the duration and quality of our existence in the world.

LeWitt’s art operates in a world of systematic execution and careful control. To argue that any of his work is emotionally driven is, basically, blasphemy. But like the boy closing his bedroom door before you can look in, LeWitt’s objective front is actually a set of limits, boundaries, and patterns that are subjectively derived and emotionally driven. The persistent question behind “Autobiography” is whether it’s possible for a “self” to objectively, clinically, and unemotionally present its own history. The black and white photograph presents itself as the perfect medium for this pseudo-scientific project. The lack of color acts to neutralize any over-sentimental content. Black and white images slip more easily into pure language than their colored counterparts, and diverse levels of content are more easily leveled. The medium of photography, in general, presents itself as an objective eye, documenting and recording the world without the complication of personal gesture. This apparent objectivity is undermined when we realize that there’s always the subjective eye behind the objective eye, and what is concealed is as important as what is revealed. The closed-door is as important, if not more important than the open room.

Revealing/Concealing Self

LeWitt presents us with many clues to discovering his true “self.” The subtext of his project is “seek and you will find.” But in the end, like a gentle trickster, LeWitt eludes us: his “self” always slips out of the frame. The real meaning of this piece comes with the realization that the “self” which ostensibly holds these photos together, has no real existence outside of the piece. Although LeWitt is the driving force behind this project, his most important role is describing a lack through his absence.

LeWitt’s photographs both invite and resist interpretation, just as the objects they depict invite and resist sentimentality. His photographs are multiple, tiny windows into his world, but they remain always and only windows. We can see through them, but only into a severely limited field. We cannot project ourselves into these tiny slivers of a world; our desire to participate is always frustrated.

The Frustration of the Voyeur

What exactly do we hope to see in a project called “Autobiography?” The heart and soul, the fears and failures, the inner hopes and dreams of Sol LeWitt? Like the girl ignoring the books and looking at the beer bottles instead, we want LeWitt to show us all his juicy, messy “Enquirer” details; not his chairs, not his pots and pans. We want to see the love notes hidden at the bottom of his sock drawer, we want to see his broken whiskey glass after a night of heavy drinking. We want to see piles of dirty laundry, and we want to hear desperate messages on his answering machine. We want the vulnerable boy behind the big famous artist.

We want it, but we’re not getting it.

As voyeurs, we nurture a secret addiction to the unknown or concealed, and recurring boredom with the known or revealed. Because of this insatiable craving, we will paradoxically never achieve the intimacy we think we desire. Once intimacy is achieved, it is thwarted by our lack of interest. But LeWitt is onto our game. He knows we really don”t want to know what we think we want to know.

Post Script

Hiding somewhere near the middle of LeWitt’s series is a photograph of a handwritten note. The note says:

“many friends are grateful to you…respect, and love you as a person and as an artist, and who are sad because you are sad. Whatever the cause of sadness, surely the above is not something to be sad about. Criticism is not everything if it is anything at all. – a critic”

The name the letter is written to is concealed by a small photograph. We can guess it’s to LeWitt but we cannot know. The strategic revealing and concealing occurring in this photo and throughout this project runs parallel to the revealing and concealing that happens in photography in general. The myth of the objective record falls apart alongside the myth of the centering “self.” In the end, there is no truth in the photographic means, just as there is no “self” to be documented truthfully. What LeWitt has given us in his “Autobiography” is a carefully directed documentation of a deliberate emptying of self.

Cindy Loehr 2000